The Science of Sleep - The Film

The Science of Sleep presents an effect called parallel synchronized randomness, which pertains to the idea that a human brain can create an incredibly complex loop. It’s not about minds communicating telepathically, but rather that we all evolve in the same direction with every step we take.

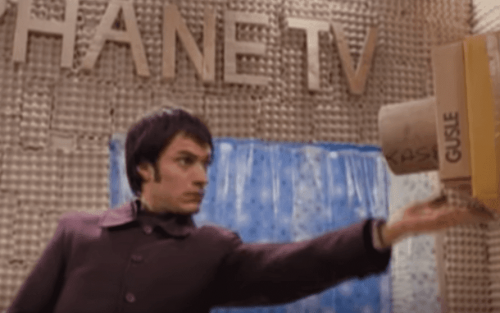

The Science of Sleep is a film about the surreal and exciting world of dreams. It describes the misadventures of Stéphane (Gael García Bernal), a young graphic artist whose brain broadcasts a television program that’s in continuous competition with his reality.

For over three thousand years, humans have been concerning themselves with dreams and consider them inexplicable. They seem to be magical and perhaps even charged with a meaning that’s hard to decipher. Sometimes, you experience such vivid dreams that you feel the need to externalize them. You want to talk about them, so you make an effort to remember and verbalize them (Guardiola, 1993).

In this act of remembrance and verbalization begins a process of ineluctable distortion. Thus, you always have a feeling that there was something else. Something that was deeper and difficult to explain and that you experienced while you were asleep.

The science of sleep

How do dreams form? The scientific community is completely unaware of the process. But there’s a wide range of interpretations, such as the one offered by The Science of Sleep.

This film won the Grand Audience Award at the Sitges Film Festival. The key to understanding it lies in its peculiar theory of reveries and in the delicate combination of complex ingredients.

First, take random thoughts. Then, add a dash of memories from your day and mix them with some memories from your past. Love, friendships, relationships, and all those words and songs you heard during the day, along with the things you saw and something personal. Then, mix it all together.

After tackling dreams in a surreal and somewhat irrational way, let’s analyze them from a more pragmatic and scientific perspective.

What are daydreams?

These are conscious experiences that take place in the form of a narrative during sleep. They’re usually involuntary dramatic representations. In addition, they involve and link mental states and types of sensory, imaginary, cognitive, affective and motor processes (Guardiola, 1993).

Although daydreams often have a particular form of strangeness and discontinuity, they’re still a representation of your personal reality. They provide a material you can contrast with recent and old memories (Guardiola, 1993).

In turn, a daydream can stay in your memory and align with future events and circumstances. You might imagine a trip you’re taking, the risks it entails, and the outcome you desire.

Daydreams have a high probability of materializing in the future, which gives dreams a pseudo-premonitory character (Guardiola, 1993).

Dreams and science

The study of the mechanisms and functions of the states of attention, wakefulness, drowsiness, and sleep by the fields of neurophysiology and psychiatry is relatively recent. In fact, the establishment of physiological measures that could be related to mental activity and states of consciousness was impossible until the middle of the last century.

Modern research on dreams highlights the importance of the content of your dreams, as they pertain to a person’s mental structure. In other words, with their thoughts while they’re awake, their concepts, and concerns (Lombardo and Foschi, 2009).

Neurolinguistics showed that the process by which you access the meaning of a word can be schematized by a module. The rationale for establishing the existence of this module lies in the behavior of patients with brain lesions that selectively affect the output and input in their dictionary.

During wakefulness, a word can trigger a series of images and concepts with similar characteristics to those that happen when you’re daydreaming. You can see cognitive elements in common with the structure of sleeping dreams through the method of free associations (Lombardo and Foschi, 2009).

The Science of Sleep presents an effect called parallel synchronized randomness, which pertains to the idea that a human brain can create an incredibly complex loop. It’s not about minds communicating telepathically, but rather that we all evolve in the same direction with every step we take.

The Science of Sleep is a film about the surreal and exciting world of dreams. It describes the misadventures of Stéphane (Gael García Bernal), a young graphic artist whose brain broadcasts a television program that’s in continuous competition with his reality.

For over three thousand years, humans have been concerning themselves with dreams and consider them inexplicable. They seem to be magical and perhaps even charged with a meaning that’s hard to decipher. Sometimes, you experience such vivid dreams that you feel the need to externalize them. You want to talk about them, so you make an effort to remember and verbalize them (Guardiola, 1993).

In this act of remembrance and verbalization begins a process of ineluctable distortion. Thus, you always have a feeling that there was something else. Something that was deeper and difficult to explain and that you experienced while you were asleep.

The science of sleep

How do dreams form? The scientific community is completely unaware of the process. But there’s a wide range of interpretations, such as the one offered by The Science of Sleep.

This film won the Grand Audience Award at the Sitges Film Festival. The key to understanding it lies in its peculiar theory of reveries and in the delicate combination of complex ingredients.

First, take random thoughts. Then, add a dash of memories from your day and mix them with some memories from your past. Love, friendships, relationships, and all those words and songs you heard during the day, along with the things you saw and something personal. Then, mix it all together.

After tackling dreams in a surreal and somewhat irrational way, let’s analyze them from a more pragmatic and scientific perspective.

What are daydreams?

These are conscious experiences that take place in the form of a narrative during sleep. They’re usually involuntary dramatic representations. In addition, they involve and link mental states and types of sensory, imaginary, cognitive, affective and motor processes (Guardiola, 1993).

Although daydreams often have a particular form of strangeness and discontinuity, they’re still a representation of your personal reality. They provide a material you can contrast with recent and old memories (Guardiola, 1993).

In turn, a daydream can stay in your memory and align with future events and circumstances. You might imagine a trip you’re taking, the risks it entails, and the outcome you desire.

Daydreams have a high probability of materializing in the future, which gives dreams a pseudo-premonitory character (Guardiola, 1993).

Dreams and science

The study of the mechanisms and functions of the states of attention, wakefulness, drowsiness, and sleep by the fields of neurophysiology and psychiatry is relatively recent. In fact, the establishment of physiological measures that could be related to mental activity and states of consciousness was impossible until the middle of the last century.

Modern research on dreams highlights the importance of the content of your dreams, as they pertain to a person’s mental structure. In other words, with their thoughts while they’re awake, their concepts, and concerns (Lombardo and Foschi, 2009).

Neurolinguistics showed that the process by which you access the meaning of a word can be schematized by a module. The rationale for establishing the existence of this module lies in the behavior of patients with brain lesions that selectively affect the output and input in their dictionary.

During wakefulness, a word can trigger a series of images and concepts with similar characteristics to those that happen when you’re daydreaming. You can see cognitive elements in common with the structure of sleeping dreams through the method of free associations (Lombardo and Foschi, 2009).

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

Fernández Guardiola, A. (1993). Las ensoñaciones: el infranqueable núcleo de la noche. Ciencias, (030).

Lombardo, GP, y Foschi, R. (2009). La psicofisiología de los sueños de Sante de Santics. Medicina nei secoli , 21 (2), 591-609.

Mata, M. J. G. (2018). Ciencia, imaginación y ensoñación en Gaston Bachelard. Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.