Spots, Moles, and Stretch Marks: Normal Skin Doesn't Make the Adverts

Written and verified by the psychologist Cristina Roda Rivera

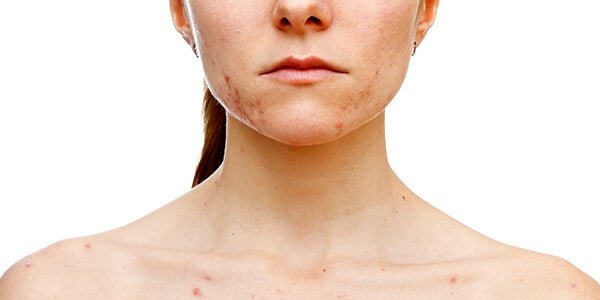

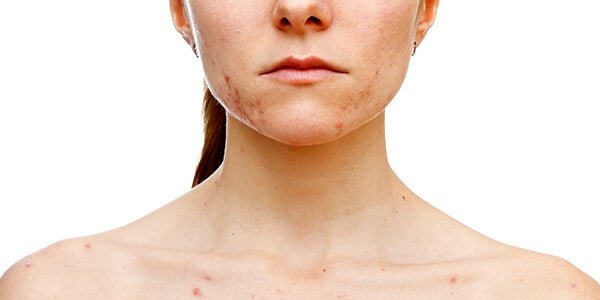

Spots, moles, and stretch marks appear on the skin of millions of people, but not in the world of advertising. Nor do the dermatological conditions of psoriasis, vitiligo, or eczema ever show up in magazines, or on TV and social media. In fact, while progress is being made in the problem of fatphobia, with the appearance of all sizes of people in adverts for clothing and cosmetics, skin conditions only appear on isolated occasions, when the cases are minimal.

In this article, we’re going to talk about the skin which is the largest organ in the body. Not accepting our skin is one of the main causes of dysmorphia. This is an alteration that causes people to feel alienated in their own bodies.

Spots, moles, and stretch marks: an unseen normality

Nothing that appears on your skin is an isolated, abnormal, ugly, or unacceptable event. It’s simply a mark on your skin, and you just have to accept it. As a matter of fact, rather than ‘body positivity’; when it comes to your skin, it’s probably better to opt for ‘body neutrality’. Body positivity involves thinking in positive terms about your body. However, this attitude can often be rather unrealistic and you may find yourself suffering from more ‘relapses’ than if you adopt a neutral attitude.

Accepting your spots, moles, and stretch marks will allow you to see them as they really are. They’re just parts of your body that you should neither love nor hate. They simply coexist alongside you and you must accept them within your mind-body relationship.

You’ll find life far more difficult if you believe that you have to hide away from others, That’s because, as a human, you’re a social being. Nevertheless, if what you see on your skin you don’t see anywhere else, you’re likely to internalize the idea that it’s something you shouldn’t exhibit. You’ll think that it’s not normal skin and that you should hide it as much as possible.

The many skin conditions that exist and are hidden

Currently, the use of tattoos to cover the skin has been democratized. It’s no longer only associated with punks, rockers, and groups of modern or vain footballers. In fact, there was even a time when having a tattoo on your body was a sign of belonging to a criminal gang.

Nowadays, it’s become such a visible and normalized practice, that it could even be said to be unusual for someone not to have a tattoo. Indeed, you often see tattooed skin in advertisements for luxury brands. However, this rarely occurs with skin conditions. In fact, ignorance leads us to think that certain dermatological conditions denote health problems or that they may even be contagious.

Everyone has skin under their clothes. Nevertheless, it’s rare that models or celebrities show themselves without layers of makeup. Their photos are also usually airbrushed. There are certain exceptions though, and some celebrities do occasionally show their skin without it being retouched.

For example, the actress and model, Cara Delevingne, has shown photos of her psoriasis. Also, the model, Winnie Harlow, revolutionized the world of fashion by showing her vitiligo on the catwalks. Needless to say, neither advertising nor cinema took the hint, and they still don’t show more diverse kinds of skins.

The movement to start showing our spots, moles, and stretch marks

This is a hidden problem of which spots, moles, and stretch marks are just an example. In fact, we should also be talking about scars, psoriasis, liver spots, warts, melasma, and birthmarks of all kinds. As a matter of fact, the idea of a clear, smooth, and blemish-free skin shouldn’t even enter the equation. Nonetheless, that’s what we’re bombarded with twenty-four hours a day in ads for body gels, creams, and swimsuits. However, why should apparently having ‘perfect’ skin suggest that these people have any more right to show themselves than those with blemishes. Why should those of us with imperfections be considered ‘weird’?

A few years ago, the model, Alba Parejo, decided to become a model and show her giant congenital melanocytic nevus, a not uncommon dermatological condition. Many thought that a person with such a skin disorder couldn’t possibly be a model, but it only took Alba one photoshoot to prove otherwise.

From her decision and that of many others, accounts began to emerge on Instagram showing how normal and natural skins are, in reality. This is how the Origen photobook was born. It’s a book by Sofía Suars. It’s full of photos but, instead of them appearing like medical diagnoses, they’re given an artistic focus.

In the pages of this book, we find women with spots, moles, and stretch marks through a lens of warmth, reality, and beauty. A beauty that’s born from everyday life and that makes us feel more human and less perfect. One that makes us curious and encourages us to explore our bodies from acceptance and not from criticism.

Conclusion

There’s still a long way to go until all skin types are democratized by the lens or the camera. In the meantime, we can start to practice exercises of acceptance, not only toward our bodies but our feelings too. It’s nice to know that the issue is now being spoken about, but it’ll be even better when we see start to see real skin on the advertising billboards. Then, everyone will start to understand that their own skin is perfectly normal and not at all strange just because it has a certain pigmentation or a few blemishes.

Spots, moles, and stretch marks appear on the skin of millions of people, but not in the world of advertising. Nor do the dermatological conditions of psoriasis, vitiligo, or eczema ever show up in magazines, or on TV and social media. In fact, while progress is being made in the problem of fatphobia, with the appearance of all sizes of people in adverts for clothing and cosmetics, skin conditions only appear on isolated occasions, when the cases are minimal.

In this article, we’re going to talk about the skin which is the largest organ in the body. Not accepting our skin is one of the main causes of dysmorphia. This is an alteration that causes people to feel alienated in their own bodies.

Spots, moles, and stretch marks: an unseen normality

Nothing that appears on your skin is an isolated, abnormal, ugly, or unacceptable event. It’s simply a mark on your skin, and you just have to accept it. As a matter of fact, rather than ‘body positivity’; when it comes to your skin, it’s probably better to opt for ‘body neutrality’. Body positivity involves thinking in positive terms about your body. However, this attitude can often be rather unrealistic and you may find yourself suffering from more ‘relapses’ than if you adopt a neutral attitude.

Accepting your spots, moles, and stretch marks will allow you to see them as they really are. They’re just parts of your body that you should neither love nor hate. They simply coexist alongside you and you must accept them within your mind-body relationship.

You’ll find life far more difficult if you believe that you have to hide away from others, That’s because, as a human, you’re a social being. Nevertheless, if what you see on your skin you don’t see anywhere else, you’re likely to internalize the idea that it’s something you shouldn’t exhibit. You’ll think that it’s not normal skin and that you should hide it as much as possible.

The many skin conditions that exist and are hidden

Currently, the use of tattoos to cover the skin has been democratized. It’s no longer only associated with punks, rockers, and groups of modern or vain footballers. In fact, there was even a time when having a tattoo on your body was a sign of belonging to a criminal gang.

Nowadays, it’s become such a visible and normalized practice, that it could even be said to be unusual for someone not to have a tattoo. Indeed, you often see tattooed skin in advertisements for luxury brands. However, this rarely occurs with skin conditions. In fact, ignorance leads us to think that certain dermatological conditions denote health problems or that they may even be contagious.

Everyone has skin under their clothes. Nevertheless, it’s rare that models or celebrities show themselves without layers of makeup. Their photos are also usually airbrushed. There are certain exceptions though, and some celebrities do occasionally show their skin without it being retouched.

For example, the actress and model, Cara Delevingne, has shown photos of her psoriasis. Also, the model, Winnie Harlow, revolutionized the world of fashion by showing her vitiligo on the catwalks. Needless to say, neither advertising nor cinema took the hint, and they still don’t show more diverse kinds of skins.

The movement to start showing our spots, moles, and stretch marks

This is a hidden problem of which spots, moles, and stretch marks are just an example. In fact, we should also be talking about scars, psoriasis, liver spots, warts, melasma, and birthmarks of all kinds. As a matter of fact, the idea of a clear, smooth, and blemish-free skin shouldn’t even enter the equation. Nonetheless, that’s what we’re bombarded with twenty-four hours a day in ads for body gels, creams, and swimsuits. However, why should apparently having ‘perfect’ skin suggest that these people have any more right to show themselves than those with blemishes. Why should those of us with imperfections be considered ‘weird’?

A few years ago, the model, Alba Parejo, decided to become a model and show her giant congenital melanocytic nevus, a not uncommon dermatological condition. Many thought that a person with such a skin disorder couldn’t possibly be a model, but it only took Alba one photoshoot to prove otherwise.

From her decision and that of many others, accounts began to emerge on Instagram showing how normal and natural skins are, in reality. This is how the Origen photobook was born. It’s a book by Sofía Suars. It’s full of photos but, instead of them appearing like medical diagnoses, they’re given an artistic focus.

In the pages of this book, we find women with spots, moles, and stretch marks through a lens of warmth, reality, and beauty. A beauty that’s born from everyday life and that makes us feel more human and less perfect. One that makes us curious and encourages us to explore our bodies from acceptance and not from criticism.

Conclusion

There’s still a long way to go until all skin types are democratized by the lens or the camera. In the meantime, we can start to practice exercises of acceptance, not only toward our bodies but our feelings too. It’s nice to know that the issue is now being spoken about, but it’ll be even better when we see start to see real skin on the advertising billboards. Then, everyone will start to understand that their own skin is perfectly normal and not at all strange just because it has a certain pigmentation or a few blemishes.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Ingram, JT (1953). El abordaje de la psoriasis. Diario Médico Británico , 2 (4836), 591.

- Napolitano, G. (2009). Dismorfia corporal y estructura subjetiva: un caso clínico. In I Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XVI Jornadas de Investigación Quinto Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. Facultad de Psicología-Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Rabito-Alcón, M. F., & Rodríguez-Molina, J. M. IMAGEN CORPORAL Y DISMORFIA MUSCULAR. AVANCES EN PSICOLOGÍA CLÍNICA, 85.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.