Projection, Repression, and Denial According to Sigmund Freud

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

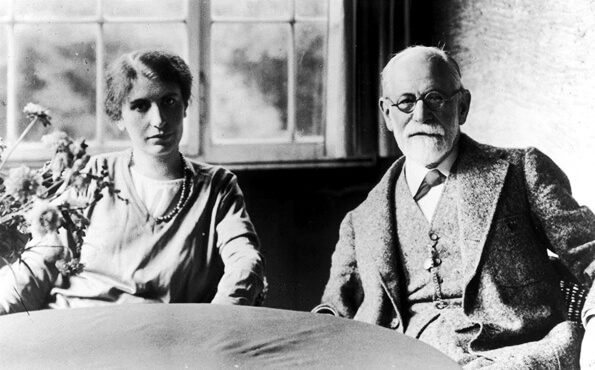

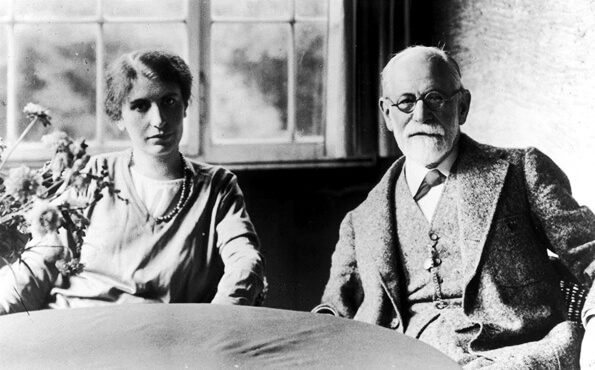

When we talk about defense mechanisms, we almost automatically visualize the face of Sigmund Freud. Some think his psychodynamic theory is now obsolete. However, assuming this is a mistake. In fact, processes such as projection, repression, and denial are a direct legacy of the Freudian school and have been inherited by the cognitive school.

That said, their names have been changed. Defense mechanisms are now called irrational cognitions. They help us understand many of the mental schemas associated with anxiety. Although Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, referents and promoters of cognitive-behavioral theory, initially rejected these unconscious mechanisms defined by Freud, in reality, they simply gave them another name.

Internal conflicts are universal

The idea that people suffer from internal conflicts and that many of these may have their origin in childhood, education, or early experiences is still valid today. That said, many of the Freudian models such as psychosexual development are completely outdated and inconsistent. On the other hand, realities such as self-deception are perfectly valid.

We’ve all used defense mechanisms at some point. After all, life, relationships, and experiences are sometimes tremendously complex. Using these strategies helps us reduce our suffering and allows us to survive in often chaotic environments. But the cost is huge. That’s because, in the long term, they plunge us into states of high psychological exhaustion.

Projection, repression, and denial

Projection, repression, and denial are possibly the best-known and most-used defense mechanisms. It doesn’t matter that it’s been more than a century since Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna Freud first defined them. We continue to apply them without even realizing it.

These resources form part of Freud’s theory of personality. In it, he explained that the mind is captive to three types of specific forces: our impulses, values (or social norms), and the ego.

The cognitive perspective

The cognitive school rejects this type of mental conflict. It doesn’t believe the idea that the mind is fragmented into an id, ego, or superego. In fact, it claims the mind is a unitary entity that, due to its own education, experiences, or interpretations, makes use of clearly irrational ideas.

These meaningless and harmful ideas plunge us into states of anxiety. They’re those erroneous interpretations that we make of things and that, in the short term, reduce our human potential. They also decrease our ability to be happy.

Therefore, it’s clear that defense mechanisms such as projection, repression, and denial cause us suffering. Rather than protect us against it, they actually prevent us from changing. For example, denying that an emotional breakup hasn’t affected us does nothing but leave us in the same situation. One in which we distrust everyone, refuse to love again and don’t even recognize that we’re suffering. We’re now going to look at the three defense mechanisms.

Projection: Putting unresolved issues on others

Projection is a really common defense mechanism. It can work in both positive and negative ways. In the latter case, we attribute shortcomings, faults, or our own defects to others. Put simply, what we criticize in others is connected to ourselves, with something about our personalities that we dislike or lack.

On the other hand, we also make use of positive projection on a recurring basis, especially when we’re in love. We do it by attributing dimensions, capacities, and virtues to our loved ones that aren’t real. This is an unconscious way of hurting ourselves because we’re creating idyllic figures that have little connection with reality.

Repression: hiding what hurts

When Freud and his daughter Anna defined projection, repression, and denial, they didn’t know the relevance of emotions to human well-being. However, in the case of repression, it’s key, because, as humans, we often tend to repress ideas, memories, and thoughts. In fact, we repress what we feel.

Putting aside what hurts is the cheapest and most desperate resource of the mind. It’s also the one that has the greatest cost for psychological balance. Indeed, it often leads to anxiety disorders, depression, etc.

Denial: denying what hurts

Out of these three defense mechanisms, denial is undoubtedly the most common. Nevertheless, just because it appears more frequently doesn’t mean it’s any less innocuous. In fact, in reality, it’s just the opposite.

As a matter of fact, in cases of addiction, denial is the most evident and harmful defense mechanism. It’s used by the alcohol addict when they say they have their alcohol use under control. It’s also implemented by the infrequent heroin addict who tells themselves that an occasional dose of the drug when they’re relaxing won’t hurt them.

In addition, denial is really common in dependent and harmful relationships. It appears in those partners who deny the evidence and refuse to see the abuse or emotional manipulation in their relationships because they think that love is like that.

These defense mechanisms are realities that are both complex and harmful and that many of us frequently use. Indeed, the defense mechanisms left behind by psychodynamic theory remain very much in force. Knowing about them, and how to detect them so we can deactivate them, will allow us to have a better quality of life.

When we talk about defense mechanisms, we almost automatically visualize the face of Sigmund Freud. Some think his psychodynamic theory is now obsolete. However, assuming this is a mistake. In fact, processes such as projection, repression, and denial are a direct legacy of the Freudian school and have been inherited by the cognitive school.

That said, their names have been changed. Defense mechanisms are now called irrational cognitions. They help us understand many of the mental schemas associated with anxiety. Although Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, referents and promoters of cognitive-behavioral theory, initially rejected these unconscious mechanisms defined by Freud, in reality, they simply gave them another name.

Internal conflicts are universal

The idea that people suffer from internal conflicts and that many of these may have their origin in childhood, education, or early experiences is still valid today. That said, many of the Freudian models such as psychosexual development are completely outdated and inconsistent. On the other hand, realities such as self-deception are perfectly valid.

We’ve all used defense mechanisms at some point. After all, life, relationships, and experiences are sometimes tremendously complex. Using these strategies helps us reduce our suffering and allows us to survive in often chaotic environments. But the cost is huge. That’s because, in the long term, they plunge us into states of high psychological exhaustion.

Projection, repression, and denial

Projection, repression, and denial are possibly the best-known and most-used defense mechanisms. It doesn’t matter that it’s been more than a century since Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna Freud first defined them. We continue to apply them without even realizing it.

These resources form part of Freud’s theory of personality. In it, he explained that the mind is captive to three types of specific forces: our impulses, values (or social norms), and the ego.

The cognitive perspective

The cognitive school rejects this type of mental conflict. It doesn’t believe the idea that the mind is fragmented into an id, ego, or superego. In fact, it claims the mind is a unitary entity that, due to its own education, experiences, or interpretations, makes use of clearly irrational ideas.

These meaningless and harmful ideas plunge us into states of anxiety. They’re those erroneous interpretations that we make of things and that, in the short term, reduce our human potential. They also decrease our ability to be happy.

Therefore, it’s clear that defense mechanisms such as projection, repression, and denial cause us suffering. Rather than protect us against it, they actually prevent us from changing. For example, denying that an emotional breakup hasn’t affected us does nothing but leave us in the same situation. One in which we distrust everyone, refuse to love again and don’t even recognize that we’re suffering. We’re now going to look at the three defense mechanisms.

Projection: Putting unresolved issues on others

Projection is a really common defense mechanism. It can work in both positive and negative ways. In the latter case, we attribute shortcomings, faults, or our own defects to others. Put simply, what we criticize in others is connected to ourselves, with something about our personalities that we dislike or lack.

On the other hand, we also make use of positive projection on a recurring basis, especially when we’re in love. We do it by attributing dimensions, capacities, and virtues to our loved ones that aren’t real. This is an unconscious way of hurting ourselves because we’re creating idyllic figures that have little connection with reality.

Repression: hiding what hurts

When Freud and his daughter Anna defined projection, repression, and denial, they didn’t know the relevance of emotions to human well-being. However, in the case of repression, it’s key, because, as humans, we often tend to repress ideas, memories, and thoughts. In fact, we repress what we feel.

Putting aside what hurts is the cheapest and most desperate resource of the mind. It’s also the one that has the greatest cost for psychological balance. Indeed, it often leads to anxiety disorders, depression, etc.

Denial: denying what hurts

Out of these three defense mechanisms, denial is undoubtedly the most common. Nevertheless, just because it appears more frequently doesn’t mean it’s any less innocuous. In fact, in reality, it’s just the opposite.

As a matter of fact, in cases of addiction, denial is the most evident and harmful defense mechanism. It’s used by the alcohol addict when they say they have their alcohol use under control. It’s also implemented by the infrequent heroin addict who tells themselves that an occasional dose of the drug when they’re relaxing won’t hurt them.

In addition, denial is really common in dependent and harmful relationships. It appears in those partners who deny the evidence and refuse to see the abuse or emotional manipulation in their relationships because they think that love is like that.

These defense mechanisms are realities that are both complex and harmful and that many of us frequently use. Indeed, the defense mechanisms left behind by psychodynamic theory remain very much in force. Knowing about them, and how to detect them so we can deactivate them, will allow us to have a better quality of life.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Kramer, U. (2010). Coping and defence mechanisms: What’s the difference? Second act. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 83(2), 207-221. doi :10.1348/147608309X475989

- Larsen, A., Bøggild, H., Mortensen, J., Foldager, L., Hansen, J., Christensen, A., & … Munk-Jørgensen, P. (2010). Psychopathology, defence mechanisms, and the psychosocial work environment. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(6), 563-577. doi:10.1177/0020764008099555

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.