Why do Children Imitate Adults?

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

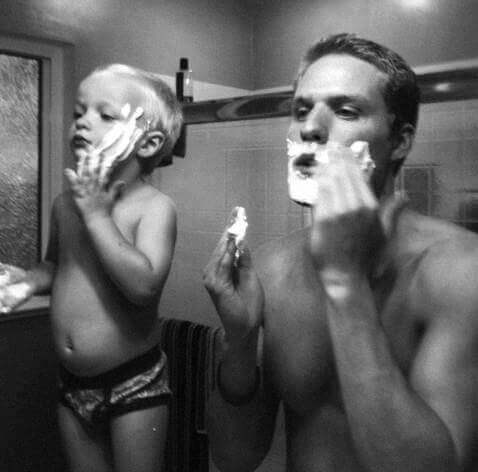

For better or for worse, children imitate adults. Almost without us realizing it, their small eyes study and hone in on us, working in behaviors, copying gestures, and internalizing words, expressions, and even roles. We know that children will never be exact copies of their parents; the imprint we leave on them, however, is decisive.

This is something that has always been clear in the area of the psychology of development. Albert Bandura, for example, a recognized psychologist in the field of social learning, has written extensively on one of its key concepts, “modeling”. According to him, people learn by imitating the behaviors they see around them, those social models they grow up or interact with.

Children don’t only imitate their parents. As we well know, they don’t simply experience isolated scenarios. Nowadays, they have more social stimulation than ever, and even “models” outside their own home or school. We also can’t forget television and those new technologies they use from a very early age.

Everything they see, hear, and happens around them influences them. We adults make up that vast theater of characters that they imitate and that will influence their conduct and even their way of understanding the world. More on this later.

Why do children imitate adults?

We know that children imitate adults, but why do they do it? Developmental psychologist Moritz Daum from the University of Zurich pointed out something interesting. This almost instinctive behavior in humans (and in other animals) serves for more than just learning: imitating also creates a sense of belonging, and it helps humans identify themselves as part of groups.

So are children really like sponges with a tendency to imitate everything they see? Furthermore, at what age do they begin to notice what surrounds them to begin modeling after it? Let’s have a look.

When do children start imitating adults?

We know that mimicking begins shortly after birth. Some newborns copy facial movements like sticking out their tongues. However, this process doesn’t reliably mature until they’re over a year old.

Babies that are six months old already understand intentional behavior. What does that mean? Well, it means that, for example, when they see their mother or father get close to pick them up, they’ll feel good. They understand what things are nice and not nice about their daily routines. All of this forms a foundation for them to recognize patterns and behaviors, and to understand that, after certain actions, others take place.

Between 19 and 24 months, children begin to copy a lot of things they see in others. They imitate their parents, their older siblings, and those they can see on TV. They do it to learn, but also to be the same as others and to feel part of a social group.

Do children choose who and what to imitate?

Before we get to the question of whether children imitate for the sake of imitating or if they tend to choose who they copy, it’s interesting to know that there are certain stimuli that appeal to them more than others. It’s been discovered that when a child is surrounded by other children of the same age, as well as adults, they’ll tend to imitate the behavior of their peers. Their mirror neurons activate much more strongly when they’re with someone with similar characteristics to themselves.

When a child needs to learn something concrete, they’ll go to adults. This principle fits in with the proximate zone of development by Lev Vygotsky. In other words, they know that, with adequate support, they can achieve another level, a new phase of greater ability. But to do this, they need “expert models”: adults.

One other detail will certainly be of interest as well. According to a study conducted at the University of London by Dr. Victoria South, children that are 18 months old already tend to imitate what’s familiar when it’s repeated a few times. In addition to the behavior, language accompanies it. Indeed, it’s the precise way in which communicative processes mature.

Children don’t know if who they’re imitating is appropriate or not

Some findings from a study at Yale University were very telling. Derek Lions, the author, showed that during a concrete period of their lives, children imitate adults excessively and mimetically. This “over-imitation” happens during the first five years. This means that they don’t have sophisticated criteria or thought processes to infer whether or not what those adults say and do is appropriate, useful, or moral.

An experiment was conducted during this study. In it, a group of adults showed some three-year-old children how to open a box. The way they did it was so complex and added so many steps that were completely useless and almost ridiculous, that it took them a very long time to open it.

When the children tried it themselves, they copied every one of the steps the adults did, including the ones that were useless.

This same experiment was applied to another group of children of the same age, who were invited to do the same thing but without seeing an example beforehand. The children resolved the problem with no extra steps.

All of these facts support our intuition. Children learn by observing everything in their surroundings, but they especially pay attention to their mothers and fathers. Being a good role model is a huge responsibility, and it might even be the most important one of all.

From us, they’ll learn the good and the bad, and every adult will be a mirror in which, for a predetermined time in their development, they see themselves. Thus, let’s make sure our own behavior – every gesture, every word – serves as a starting point for our children towards happiness and well-being.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Southgate, V., Chevallier, C., & Csibra, G. (2009). Sensitivity to communicative relevance tells young children what to imitate. Developmental Science, 12(6), 1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00861.x

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.