Autonomy and heteronomy, an important difference

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist and teacher who thoroughly studied the subject of moral judgments. He developed the concepts of autonomy and heteronomy.

These refer to how a person learns and applies moral standards. From his perspective, this ethical development is closely linked to the development of intelligence and should lead us from moral dependence on others to independence.

According to Piaget, when a child is born, they do not have enough brain development to understand the concepts of “good” or “bad”.

This is called “anomie“, which means there is no kind of moral conscience or even something that resembles it. The baby simply acts according to its needs, regardless of whether what it does affects others, unless it seeks a specific reaction.

“The best government is that which teaches us to govern ourselves”.

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe-

As the child grows, they become aware of the moral value of their actions. Their parents, their teachers and all authority figures are responsible for instilling the child’s moral awareness. The child then acts according to what others approve or disapprove. This is called heteronomy.

Later, when the process of brain development is completed, a new phase of development appears. The child evolves and gradually achieves autonomy, in ethical and moral terms. This means that they learn to act on the basis of what their own conscience dictates.

Autonomy, heteronomy, and evolution of rules

According to Piaget’s perspective, the concept of “rules” evolves according to moral development. Rules are those commands that in principle seek positive behaviors in individuals and/or groups. We believe rules are more legitimate (universal) when they exist to avoid conflicts, promote growth, respect, and, above all, justice. It’s important to keep this in mind since there are also destructive rules.

What exists in principle is a “motor rule”. This kind of rule simply follows some basic instructions. The adult must intervene directly or physically for this. An example is when a child is walking towards a dangerous place and the adult intervenes to prevent it.

What comes next is “coercive rule”. This occurs in the first years of childhood. In this stage, the child follows the norm simply because an adult says they must.

They don’t even think to question it, since everything the adult says about morals seems to be almost sacred. For the child, breaking a rule, however absurd, is a reason for punishment. This is in the heteronomy stage.

Then “rational rule” appears. This rule is not enforced by others, but rather by the individual according to what others think. They are aware of the value of the norm they are carrying out. If the rule or norm is irrational, they don’t follow it, acting autonomously and not according to authority. Obedience is no longer unconditional.

Justice, equity, and cooperation

For those who have remained in the heteronomy stage, good is what the majority does, according to an authority. The individual thinks that if a rule exists, it is because it is good.

They don’t look at the moral contents as much as they look at who makes the rule. This does not only apply to children, but also to adults. That explains why many people and societies are even able to act against themselves because of certain rules.

In heteronomy, intention is not analyzed. The only thing reviewed is the result of the behavior, not the motivation behind it. Piaget asked a group of children to judge two actions: in one, a child spilled ink on a tablecloth, unintentionally, but the stain was huge.

In the other, a child intentionally spilled a drop of ink. When asked who had the worst behavior, the children replied that it was the child with the biggest stain.

One of the main characteristics of heteronomy is rigidity. No intentions, no contexts, and no reasons are evaluated. The only thing we see is to what extent a norm was followed. This is what many adults do when facing infidelity, failure to meet a goal, or any transgressive behavior.

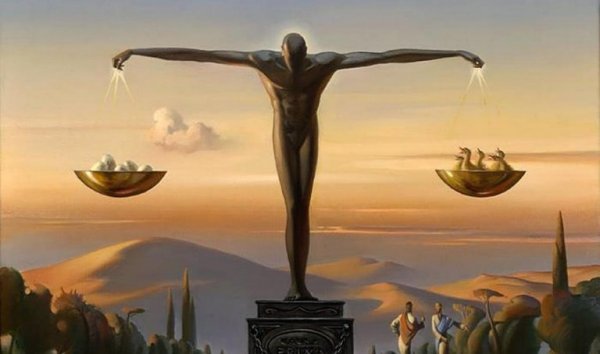

In autonomy, on the other hand, intention is a decisive factor. So is justice. If a behavior goes against the rules but promotes justice, it is valid.

There is a high regard for morality as a means for equality, cooperation, and respect for others. Whether or not it is also a rule is less important. In this sense, we would surely build better societies if we developed individual autonomy.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.