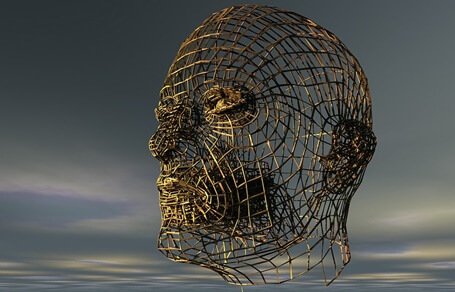

The Anxious Brain and the Worry Cycle

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

The anxious brain usually experiences more worry than fear. It feels exhausted and with limited resources, due to the repetitive worries and an ongoing feeling of threat and pressure. Neuroscience tells us that this is the result of amygdala hyperactivity.

Napoleon Bonaparte used to say that we should throw off our worries like we take off our clothes at night in order to sleep more comfortably. However, we all worry constantly.

Ad Kerkhof, who is a psychologist at Vrije University Amsterdam, pointed out that worrying about certain things is perfectly understandable and normal. The problem is when we worry about the same things day after day.

There’s also a question that neuroscience experts have been asking themselves for a long time: What happens in our brain that leads us to drift into those psychological paths? Why do we magnify our worries to the point that we can’t stop thinking about them?

“Worrying is stupid. It’s like walking around with an umbrella waiting for it to rain.”

-Wiz Khalifa-

The anxious brain and the amygdala

An anxious brain is the opposite of an efficient brain. While the latter optimizes the resources at hand, has a proper emotional balance, and keeps stress levels low, the former is the exact opposite. It’s characterized by hyperactivity, exhaustion, and even unhappiness.

We know what causes anxiety and what it’s like to think about things over and over again. However, what happens in our brain when we’re worried? A study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2007 gave us an interesting answer.

Emotions and pain

- Doctors Stein, Simmons, and Feinstein from the University of California pointed out that an increase in the reactivity of the amygdala and insular cortex lead to an anxious brain.

- Also, these brain areas are in charge of anticipating a potential threat in our environment. Therefore, they encourage an emotional state as a reaction to those stimuli.

- However, when we’re anxious for weeks or even months, another interesting process occurs. Our prefrontal cortex, which favors self-control and rational thinking, stops being as effective as it normally is.

In other words, our amygdala takes control, thus increasing the intensity of our obsessive thoughts. Plus, another aspect worth mentioning is that anxiety causes pain in the brain. The activation of the anterior cingulate cortex seems to suggest this is exactly what happens.

Some people are prone to extreme anxiety

We know that worrying excessively can lead to anxiety. But why are some people able to manage their daily worries, while others keep falling in those obsessive and ruminating cycles over and over again?

- A study by doctors Mark H. Freeston and Josée Rhéaume from the University of Quebec tells us that there are people who use their worries efficiently. They know how to discard the negative, take control, reduce the feeling of guilt, and apply a proactive approach to find a solution to any problem. Other people just get stuck in negative situations.

- This study demonstrated that the anxious brain may have a genetic component.

- Highly sensitive people are prone to experiencing these psychological conditions.

How to handle worry in an effective way

No one wants to have an anxious brain. We all want to have an efficient, healthy, and strong brain. To achieve this, we must learn to control our worries. This is a skill that will keep us from suffering from anxiety.

Let’s go over some very simple keys to train your worry-control muscle:

There’s time to live and there’s time to worry

- This strategy is as simple as it is efficient. It’s based on a cognitive behavioral tool that suggests taking a specific time of the day to worry: 15 minutes in the morning and 15 minutes in the evening.

- During this time, we must think about what worries us, as well as possible solutions.

- We can’t think about things that worry us outside these time periods.

Good memories as anchors

You must be prepared to push your worries aside. Creating positive and relaxing “anchors” is a good way to do this. For example, remembering a positive feeling or memory can help.

To conclude, it’s necessary that you keep the following in mind: these strategies take time and require willpower, perseverance, and determination. It’s not easy to tame your mind and calm your anxious brain down.

However, it is possible to take control of your anxious brain. All you have to do is stop paying attention to your worries, let go of the pressure, and set new goals.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Shin, L. M., & Liberzon, I. (2010, January). The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.83

- Sánchez-Navarro, JP, y Román, F. (2004). Amigdala, corteza prefrontal y especializacion hemisferica en la experiencia y expresion emocional. Anales de Psicología , 20 , 223–240. https://doi.org/10.2174/138527205774913088

- Stein, M. B., Simmons, A. N., Feinstein, J. S., & Paulus, M. P. (2007). Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(2), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.318

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.