The Addict's Brain: Anatomy of Compulsion and Need

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

People often say that there are between three and five people or forces going on in the addict’s brain. There’s one who has no willpower and only cares about feeling good, which generates or perpetuates the addiction. Another anticipates what the addiction will create in the short and long-term: anxiety, depression, and withdrawal symptoms. Their other “selves” are loneliness and fear.

The presence of all these voices isn’t related at all to the classic profile of someone with multiple personalities. This is because if there’s something that we should know about addictions, it’s that they completely fragment our own identity, thoughts, and willpower. Addiction is like a thief waiting patiently in a corner to invade one’s property and disrupt every apex and fragment of our brain, mind, and dignity.

“I was convinced that for some mysterious reason I was invulnerable and wouldn’t get hooked. But addiction doesn’t negotiate and little by little it spread inside me like fog.”

-Eric Clapton-

Techniques that lead to recovery

Sometimes even the finest techniques of cognitive-behavioral therapy don’t make that thief turn around and give up. Thus, another strategy to redirect an addict’s brain is to use a medical and pharmacological approach.

However, we shouldn’t get confused. The medications used to relieve withdrawal symptoms and many associated side effects can become addictive themselves. What’s more, those neural pathways that create addiction, as well as certain thoughts and behaviors, don’t always respond to the first treatments. The road to recovery can be a long and expensive process that requires a multidimensional approach.

This means that many people with chemical or behavioral addictions find themselves in authentic blind alleys. Each person needs to find a strategy that works for them and their needs and characteristics.

The addict’s brain: The compulsion of the emotional vacuum

When we talk about addiction, it’s common to immediately see in our minds someone using opiates, hallucinogens, or designer substances, such as amphetamines. We forget that addiction has many faces, forms, and behaviors. There are the shopaholics and people who can’t separate themselves from their cell phones. There are people who are addicted to sex, sports, games, and certain foods.

An addict isn’t just an alcoholic or someone who uses hard drugs. In essence, addiction is characterized by a physical dependence on a substance or a certain behavior. However, the end result is always the same: an inability to function normally in society. Addicts also tend to suffer a lot.

What do all addiction processes have in common?

All addictions do have something in common. At the 4th International Conference on Behavioral Addictions held in Budapest last year and promoted by the Journal of Behavioral Addictions, experts concluded that the common denominator in all cases of addiction is compulsion.

Naomi Fineberg, a psychiatrist and neuropharmacology specialist at the NHS Foundation Trust (HPFT), works in Hertfordshire, England. She explained that people with addictions have obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as low cognitive flexibility and limited or non-existent personal goals.

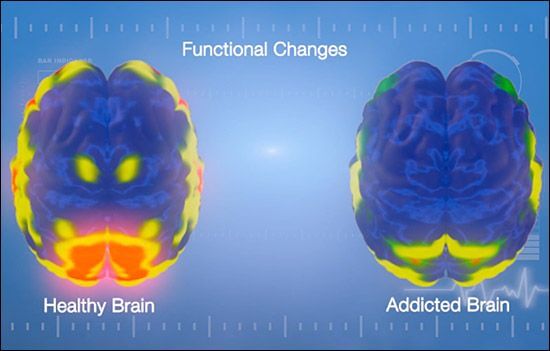

The addict’s brain always shows certain alterations in the ventral regions of the prefrontal cortex, an area related to emotional meaning and capacity for control.

Thus, something that many neurologists and specialists in addiction conclude is the following: the people who are dependent on a substance or behavior replace their addictions with an emotional need. However, in their quest to satisfy this gap, they derive in compulsive behaviors. These behaviors are impossible for the brain to control.

The neurological mechanism of addiction

The addict’s brain works differently. Its only objective, its biggest priority and need, is to find that well-being that it gets from the use of that substance or said behavior. This behavior or substance generates a momentary and limited pleasure. Little by little, that external “stimulant” replaces the natural rewards of the organism itself, and the brain needs more.

- Dopamine in any addiction process is key. The reason? Dopamine generates the desire. It makes the rest of the brain regions be directed towards that same need. The corpus striatum, for example, is the first to start. It “recruits” structures such as the mesencephalon and the orbitofrontal cortex. The whole brain understands that this substance or behavior is a priority and begins to focus on that single objective.

- In general, all drugs generate serious alterations in the activity of the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system. Thus, if the consumption becomes chronic, neuroadaptive and neuroplastic changes will take place to the point of completely altering the structure of this system.

- The prefrontal cortex is one of the most affected regions of the brain. Drastic changes happen here. Our emotions and how we regulate them becomes altered, as well as our cognitive processes. It becomes hard for us to focus our attention, reason clearly, control our own behavior, and make decisions.

There’s another aspect that we have to talk about. When we talk about alcohol and drug consumption, the changes that take place in the brain are immense. They can even be devastating. The alterations generated in the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the striate are irreversible in many cases.

Is addiction a chronic illness?

As we’ve pointed out, the addicted brain can sometimes show chronic alterations. Poisoning by certain substances impairs short-term memory and the ability to store new information. Likewise, alcohol, for example, has a serious impact on the cerebellum, which can interfere in aspects such as motor coordination.

- Thus, experts from the National Institute on Drug Abuse made it clear that addiction is basically a recurrent and chronic brain disease. However, there are already many neurologists who question this claim.

- The key to such an assertion is a concept that we all know and have heard about on more than one occasion: cerebral neuroplasticity.

- The brain isn’t like the heart, the stomach, or the pancreas. The brain has an exceptional virtue: it’s designed to change, produce new neural connections, learn, and create new tissues and nerve cells. Therefore, if our brain hadn’t changed throughout our lives, we’d be in a coma. We all evolve, change, and learn new abilities.

The implications

What does this mean and what does it have to do with an addict’s brain? Basically, it means that there’s hope, just as many patients with brain damage are able to improve certain aspects of their lives. The same can happen in people who suffer from addiction.

Doing this, in essence, involves creating new synaptic patterns based on new behaviors and thoughts. This is a door to change that many clinics and rehabilitation centers are adopting with good success rates. Science and knowledge about the human brain are constantly evolving. Hopefully, this will make it easier to help those addicts who truly need it.

People often say that there are between three and five people or forces going on in the addict’s brain. There’s one who has no willpower and only cares about feeling good, which generates or perpetuates the addiction. Another anticipates what the addiction will create in the short and long-term: anxiety, depression, and withdrawal symptoms. Their other “selves” are loneliness and fear.

The presence of all these voices isn’t related at all to the classic profile of someone with multiple personalities. This is because if there’s something that we should know about addictions, it’s that they completely fragment our own identity, thoughts, and willpower. Addiction is like a thief waiting patiently in a corner to invade one’s property and disrupt every apex and fragment of our brain, mind, and dignity.

“I was convinced that for some mysterious reason I was invulnerable and wouldn’t get hooked. But addiction doesn’t negotiate and little by little it spread inside me like fog.”

-Eric Clapton-

Techniques that lead to recovery

Sometimes even the finest techniques of cognitive-behavioral therapy don’t make that thief turn around and give up. Thus, another strategy to redirect an addict’s brain is to use a medical and pharmacological approach.

However, we shouldn’t get confused. The medications used to relieve withdrawal symptoms and many associated side effects can become addictive themselves. What’s more, those neural pathways that create addiction, as well as certain thoughts and behaviors, don’t always respond to the first treatments. The road to recovery can be a long and expensive process that requires a multidimensional approach.

This means that many people with chemical or behavioral addictions find themselves in authentic blind alleys. Each person needs to find a strategy that works for them and their needs and characteristics.

The addict’s brain: The compulsion of the emotional vacuum

When we talk about addiction, it’s common to immediately see in our minds someone using opiates, hallucinogens, or designer substances, such as amphetamines. We forget that addiction has many faces, forms, and behaviors. There are the shopaholics and people who can’t separate themselves from their cell phones. There are people who are addicted to sex, sports, games, and certain foods.

An addict isn’t just an alcoholic or someone who uses hard drugs. In essence, addiction is characterized by a physical dependence on a substance or a certain behavior. However, the end result is always the same: an inability to function normally in society. Addicts also tend to suffer a lot.

What do all addiction processes have in common?

All addictions do have something in common. At the 4th International Conference on Behavioral Addictions held in Budapest last year and promoted by the Journal of Behavioral Addictions, experts concluded that the common denominator in all cases of addiction is compulsion.

Naomi Fineberg, a psychiatrist and neuropharmacology specialist at the NHS Foundation Trust (HPFT), works in Hertfordshire, England. She explained that people with addictions have obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as low cognitive flexibility and limited or non-existent personal goals.

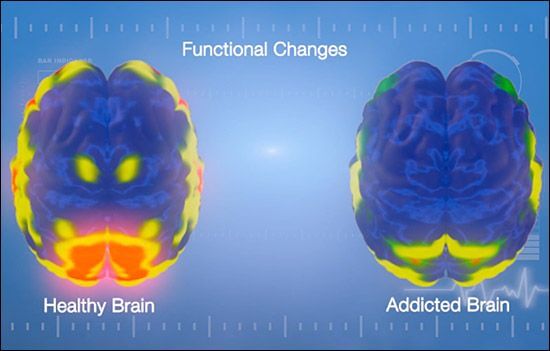

The addict’s brain always shows certain alterations in the ventral regions of the prefrontal cortex, an area related to emotional meaning and capacity for control.

Thus, something that many neurologists and specialists in addiction conclude is the following: the people who are dependent on a substance or behavior replace their addictions with an emotional need. However, in their quest to satisfy this gap, they derive in compulsive behaviors. These behaviors are impossible for the brain to control.

The neurological mechanism of addiction

The addict’s brain works differently. Its only objective, its biggest priority and need, is to find that well-being that it gets from the use of that substance or said behavior. This behavior or substance generates a momentary and limited pleasure. Little by little, that external “stimulant” replaces the natural rewards of the organism itself, and the brain needs more.

- Dopamine in any addiction process is key. The reason? Dopamine generates the desire. It makes the rest of the brain regions be directed towards that same need. The corpus striatum, for example, is the first to start. It “recruits” structures such as the mesencephalon and the orbitofrontal cortex. The whole brain understands that this substance or behavior is a priority and begins to focus on that single objective.

- In general, all drugs generate serious alterations in the activity of the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system. Thus, if the consumption becomes chronic, neuroadaptive and neuroplastic changes will take place to the point of completely altering the structure of this system.

- The prefrontal cortex is one of the most affected regions of the brain. Drastic changes happen here. Our emotions and how we regulate them becomes altered, as well as our cognitive processes. It becomes hard for us to focus our attention, reason clearly, control our own behavior, and make decisions.

There’s another aspect that we have to talk about. When we talk about alcohol and drug consumption, the changes that take place in the brain are immense. They can even be devastating. The alterations generated in the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the striate are irreversible in many cases.

Is addiction a chronic illness?

As we’ve pointed out, the addicted brain can sometimes show chronic alterations. Poisoning by certain substances impairs short-term memory and the ability to store new information. Likewise, alcohol, for example, has a serious impact on the cerebellum, which can interfere in aspects such as motor coordination.

- Thus, experts from the National Institute on Drug Abuse made it clear that addiction is basically a recurrent and chronic brain disease. However, there are already many neurologists who question this claim.

- The key to such an assertion is a concept that we all know and have heard about on more than one occasion: cerebral neuroplasticity.

- The brain isn’t like the heart, the stomach, or the pancreas. The brain has an exceptional virtue: it’s designed to change, produce new neural connections, learn, and create new tissues and nerve cells. Therefore, if our brain hadn’t changed throughout our lives, we’d be in a coma. We all evolve, change, and learn new abilities.

The implications

What does this mean and what does it have to do with an addict’s brain? Basically, it means that there’s hope, just as many patients with brain damage are able to improve certain aspects of their lives. The same can happen in people who suffer from addiction.

Doing this, in essence, involves creating new synaptic patterns based on new behaviors and thoughts. This is a door to change that many clinics and rehabilitation centers are adopting with good success rates. Science and knowledge about the human brain are constantly evolving. Hopefully, this will make it easier to help those addicts who truly need it.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.