Wilhelm Stekel and His Views on Psychoanalysis

The name Wilhelm Stekel isn’t very well-known in psychoanalysis. He didn’t become famous like many of his colleagues, although he played a big part in the foundation of this school of thought and came up with many important concepts.

Stekel was born in 1868 in a town called Boiany in present-day Ukraine. He was born into an Orthodox Jewish family that was successful in the world of trade. Stekel studied medicine in Vienna, Austria and opened an office as a general practitioner. But he was mostly interested in the mind and sexuality.

His fascination with psychopathological phenomena led him to publish an article called “On Coitus in Childhood” in 1895. It got Freud’s attention. It made him believe that Stekel was intuitive, very intelligent, and a powerful writer.

“The mark of the immature man is that he wants to die nobly for a cause, while the mark of the mature man is that he wants to live humbly for one.”

-Wilhelm Stekel-

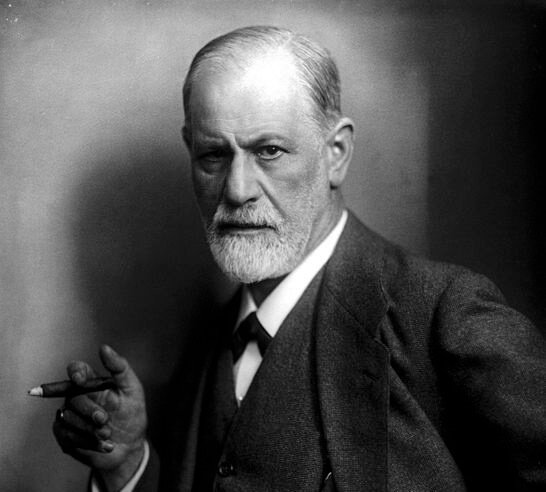

Wilhelm Stekel, Freud, and psychoanalysis

Stekel reached out to Freud because he needed to be psychoanalyzed. He was impotent and underwent treatment with Freud for eight weeks (48 sessions). The sessions didn’t seem to solve his problem, although they did help him manage his anxiety.

He was also a compulsive masturbator and even wrote a book called Auto-Eroticism: A Psychiatric Study on Onanism and Neurosis, which was published after his death. Sexuality extremely fascinated him.

In the end, he went from being Freud’s patient to his disciple. Stekel took Freud’s theories to heart. When Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, Stekel wrote an amazing review of it. He was one of the few who saw how important the book was, which made Freud gain a lot of respect for him.

A tense relationship

Wilhelm Stekel became a part of all the major psychoanalytic discoveries as of 1902. In 1908, he published a book called Conditions of Nervous Anxiety and Their Treatment. Freud wrote the book’s preface and considered Stekel a friend.

But Stekel behaved very strangely, which is why he started to test Freud’s patience. Freud couldn’t stand his rudeness and “indecency”.

Stekel talked about his own symptoms and masturbation without any shame. Freud disagreed completely with this. Stekel even talked about things that had never happened to him at the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society. Freud knew what was true and what wasn’t because he had psychoanalyzed Stekel.

Things reached their breaking point when Stekel wrote an article about the relationship between names and destiny. He talked about how names had influenced the job choice and several other aspects of many of his patients. Freud criticized him for publishing those patients’ names. Stekel responded that he didn’t care because he had made them all up.

Stekel’s banishment

After that, Freud chose to exclude Stekel from both his professional and personal circles. He even wrote a letter to Carl Jung to tell him that Stekel was “an absolute pig”.

Freud asked him to quit his position as the head of VPS’s journal, but he refused. Thus, Freud made the rest of Stekel’s colleagues distance themselves from him. That marked the end of their relationship.

In his autobiography, Stekel said that Freud stole many of his ideas. Among other things, he said that the concepts of the death drive and anxiety were his and that Freud had plagiarized them.

Unlike other controversial figures in psychoanalysis, Wilhelm Stekel didn’t try to start a new school of thought. He was faithful to the basic principles of Freudian psychoanalysis. He got married twice, had two children, and took his own life in 1940.

The name Wilhelm Stekel isn’t very well-known in psychoanalysis. He didn’t become famous like many of his colleagues, although he played a big part in the foundation of this school of thought and came up with many important concepts.

Stekel was born in 1868 in a town called Boiany in present-day Ukraine. He was born into an Orthodox Jewish family that was successful in the world of trade. Stekel studied medicine in Vienna, Austria and opened an office as a general practitioner. But he was mostly interested in the mind and sexuality.

His fascination with psychopathological phenomena led him to publish an article called “On Coitus in Childhood” in 1895. It got Freud’s attention. It made him believe that Stekel was intuitive, very intelligent, and a powerful writer.

“The mark of the immature man is that he wants to die nobly for a cause, while the mark of the mature man is that he wants to live humbly for one.”

-Wilhelm Stekel-

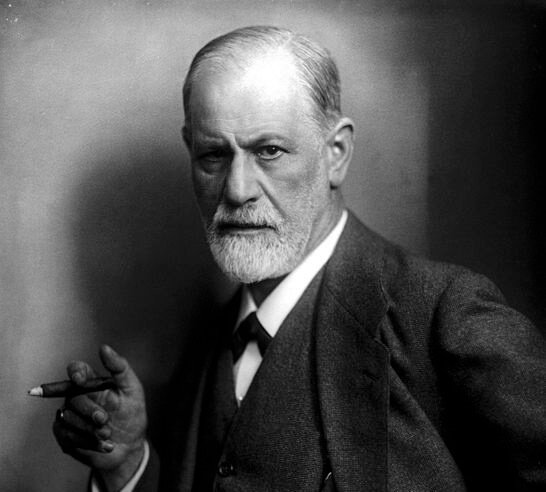

Wilhelm Stekel, Freud, and psychoanalysis

Stekel reached out to Freud because he needed to be psychoanalyzed. He was impotent and underwent treatment with Freud for eight weeks (48 sessions). The sessions didn’t seem to solve his problem, although they did help him manage his anxiety.

He was also a compulsive masturbator and even wrote a book called Auto-Eroticism: A Psychiatric Study on Onanism and Neurosis, which was published after his death. Sexuality extremely fascinated him.

In the end, he went from being Freud’s patient to his disciple. Stekel took Freud’s theories to heart. When Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, Stekel wrote an amazing review of it. He was one of the few who saw how important the book was, which made Freud gain a lot of respect for him.

A tense relationship

Wilhelm Stekel became a part of all the major psychoanalytic discoveries as of 1902. In 1908, he published a book called Conditions of Nervous Anxiety and Their Treatment. Freud wrote the book’s preface and considered Stekel a friend.

But Stekel behaved very strangely, which is why he started to test Freud’s patience. Freud couldn’t stand his rudeness and “indecency”.

Stekel talked about his own symptoms and masturbation without any shame. Freud disagreed completely with this. Stekel even talked about things that had never happened to him at the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society. Freud knew what was true and what wasn’t because he had psychoanalyzed Stekel.

Things reached their breaking point when Stekel wrote an article about the relationship between names and destiny. He talked about how names had influenced the job choice and several other aspects of many of his patients. Freud criticized him for publishing those patients’ names. Stekel responded that he didn’t care because he had made them all up.

Stekel’s banishment

After that, Freud chose to exclude Stekel from both his professional and personal circles. He even wrote a letter to Carl Jung to tell him that Stekel was “an absolute pig”.

Freud asked him to quit his position as the head of VPS’s journal, but he refused. Thus, Freud made the rest of Stekel’s colleagues distance themselves from him. That marked the end of their relationship.

In his autobiography, Stekel said that Freud stole many of his ideas. Among other things, he said that the concepts of the death drive and anxiety were his and that Freud had plagiarized them.

Unlike other controversial figures in psychoanalysis, Wilhelm Stekel didn’t try to start a new school of thought. He was faithful to the basic principles of Freudian psychoanalysis. He got married twice, had two children, and took his own life in 1940.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Stekel, W. (1961). La voluntad de vivir (No. 04; BF613, S8 1961.).

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.