José Ortega y Gasset - A Regenerationist

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

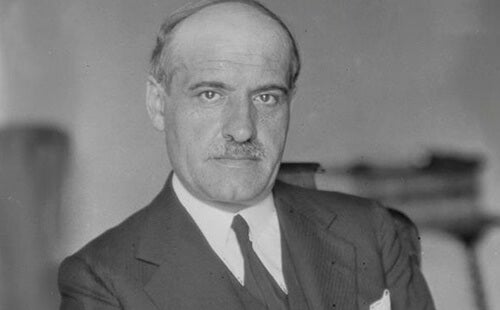

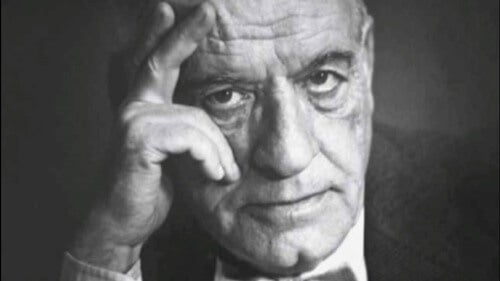

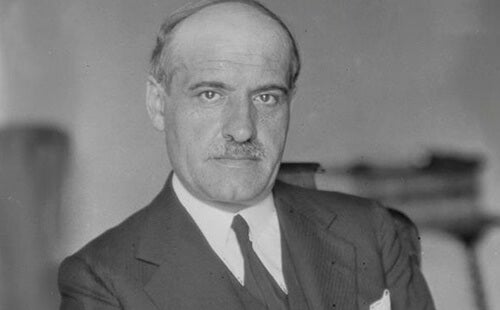

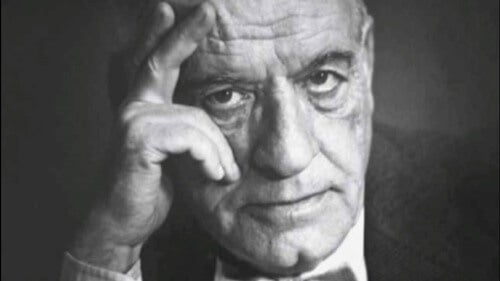

José Ortega y Gasset was one of the most outstanding Spanish philosophers. Intellectual, essayist, journalist, speaker… His liberal and regenerative discourse contained the essence of perspectivism and vital reason. He belonged to the movement of Noucentisme and the Generation of 14, that also include figures such as Pablo Picasso or Juan Ramón Jiménez.

His most representative works, such as Invertebrate Spain (1921), The Dehumanization of Art and Other Essays on Art, Culture, and Literature (1925), and The Revolt of the Masses (1930), described a very relevant page in human history. They were about the social and intellectual situation of Europe in the middle of the 20th century. Ortega reflected like no other the irruption of the liberated masses that finally left the elite aside. They did so to express themselves through art, civic values, and liberal philosophy.

Keep in mind that this famous philosopher developed his work in a highly complex context. The rise of communism confronting fascism. Unionism with nationalisms, and in turn, with the popular class. They were gaining a foothold through cultural movements and also consumerism.

“I am I and my circumstance; and, if I do not save it, I do not save myself.” This phrase, so representative of José Ortega y Gasset, implied the influence of this scenario. You’re to assume that although you can’t control your own circumstances, there’s always a certain amount of space in which to be responsible for yourself and generate changes.

The biography of José Ortega y Gasset

José Ortega y Gasset was born into a wealthy family in Madrid, Spain in 1883. His mother was Dolores Gasset, daughter of Eduardo Gasset, founder of the newspaper El Imparcial, and that his own father, José Ortega Munilla, directed. Thus, it was a home closely linked to philosophy, intellectualism, journalism, and also politics.

All of this undoubtedly made him aware of what his personal path should be. He studied philosophy and letters in Bilbao and later finished his studies in Berlin. He began working as a professor of psychology and ethics after graduating and, in 1910, he passed the test to be a professor of Metaphysics at one of the universities of Madrid.

From the year 1920, his life as an academic took a different course. He founded Revista de Occidente, a demanding liberal publication to bring more innovative intellectual currents, open-minded and selected. Later, there were translations of new philosophical trends from writers such as Edmund Husserl or Bertrand Russell.

José Ortega y Gasset’s goal was as concrete as it was ambitious. He wished to bring into his country the renovating air that was already in Europe. He wanted people to wake up and rebel against conservatism.

“Life is a series of collisions with the future; it is not the sum of what we have been, but what we yearn to be.”

-José Ortega y Gasset-

The political stage of José Ortega y Gasset

Ortega y Gasset was elected deputy during the Second Republic. Then, together with Marañón and Pérez de Ayala, he founded the Agrupación al Servicio de la República. He held that position with great hope until, little by little, he began to feel certain discrepancies with the wrong course — carried away by the Republic, in his opinion. However, everything changed in 1936 with the Civil War.

He had no choice but to live in exile. He spent about 10 years as a refugee in France, the Netherlands, Argentina, and Portugal. His return in 1945 allowed him to meet many like-minded intellectuals he continued working with. Thus, he founded the Humanities Institute in 1948 with Julián Marías.

From that moment on, his figure once again stood out among the Spanish cultural scene. He was a professor of several philosophy students and reflected his liberal ideas in various newspapers, books, and essays. He founded the newspaper El Sol (1917), the magazine España (1915), and Revista de Occidente (1923).

Likewise, José Ortega y Gasset was a figure of undeniable relevance that later inspired the generation of ’27. His wake as a regenerationist intellectual, personal ideology, and philosophical principles, crossed borders that reached Europe and Latin America. He died in 1955 at the age of 72 at his home in Madrid.

José Ortega y Gasset’s masterpiece, The Revolt of the Masses

José Ortega y Gasset was a part of three basic trends. The first was Noucentisme, a movement for cultural renewal. The second was perspectivism (a concept established by Friedrich Nietzsche that extolled the idea that there’s no single truth and each person has a different perspective).

The third approach, crucial to his work, was an idea he developed. It was about vitalism, an idea of where to assume the inevitable interrelation between a person and their reality. These pillars were key when writing one of his most representative works, The Revolt of the Masses in 1930.

The danger of a community that doesn’t reason

A structuring aspect you can appreciate on each page of The Revolt of the Masses is the end of conservatism and the beginning of something new that isn’t always as positive as you may think. In the regeneration that modern life brings, there are a series of challenges that also arise. Through them, the person, a modern and apparently liberated citizen, has no choice but to understand.

- First of all, the concept of “mass” has nothing to do with the term used by Marxists.

- The mass, for Ortega y Gasset, is about individualization. That is, they’re no longer isolated or individual figures. Instead, they’re a community often conditioned by their emotions rather than by reasoning.

- Those masses already appear in the new democracies of the time. Therefore, even if you leave authoritarianism behind, other dangers arise. Because collectives can also align with other figures in public life.

- In the book, Gasset made reference to the acts of vandalism that occurred in France in the late 30s. Thousands of young people there took to the streets and started burning cars to vent their anger guided or motivated by other people who sought to “ignite the masses”.

A very present legacy

The Revolt of the Masses is a key work of philosopher José Ortega y Gasset from which, as you can see, emanate multiple ideas that are still relevant. In fact, they’re quite relevant and invite you to reflect on something that he wanted to convey to his readers: you’re threatening democracy when you act as gregarious groups.

Humans are a part of a historical and social context there’s no escape from. However, you must separate yourself from the masses that act on instinct. Thus, you must act as an individual, responsible for yourself and always attentive to those who dare to veto their own freedoms.

José Ortega y Gasset was one of the most outstanding Spanish philosophers. Intellectual, essayist, journalist, speaker… His liberal and regenerative discourse contained the essence of perspectivism and vital reason. He belonged to the movement of Noucentisme and the Generation of 14, that also include figures such as Pablo Picasso or Juan Ramón Jiménez.

His most representative works, such as Invertebrate Spain (1921), The Dehumanization of Art and Other Essays on Art, Culture, and Literature (1925), and The Revolt of the Masses (1930), described a very relevant page in human history. They were about the social and intellectual situation of Europe in the middle of the 20th century. Ortega reflected like no other the irruption of the liberated masses that finally left the elite aside. They did so to express themselves through art, civic values, and liberal philosophy.

Keep in mind that this famous philosopher developed his work in a highly complex context. The rise of communism confronting fascism. Unionism with nationalisms, and in turn, with the popular class. They were gaining a foothold through cultural movements and also consumerism.

“I am I and my circumstance; and, if I do not save it, I do not save myself.” This phrase, so representative of José Ortega y Gasset, implied the influence of this scenario. You’re to assume that although you can’t control your own circumstances, there’s always a certain amount of space in which to be responsible for yourself and generate changes.

The biography of José Ortega y Gasset

José Ortega y Gasset was born into a wealthy family in Madrid, Spain in 1883. His mother was Dolores Gasset, daughter of Eduardo Gasset, founder of the newspaper El Imparcial, and that his own father, José Ortega Munilla, directed. Thus, it was a home closely linked to philosophy, intellectualism, journalism, and also politics.

All of this undoubtedly made him aware of what his personal path should be. He studied philosophy and letters in Bilbao and later finished his studies in Berlin. He began working as a professor of psychology and ethics after graduating and, in 1910, he passed the test to be a professor of Metaphysics at one of the universities of Madrid.

From the year 1920, his life as an academic took a different course. He founded Revista de Occidente, a demanding liberal publication to bring more innovative intellectual currents, open-minded and selected. Later, there were translations of new philosophical trends from writers such as Edmund Husserl or Bertrand Russell.

José Ortega y Gasset’s goal was as concrete as it was ambitious. He wished to bring into his country the renovating air that was already in Europe. He wanted people to wake up and rebel against conservatism.

“Life is a series of collisions with the future; it is not the sum of what we have been, but what we yearn to be.”

-José Ortega y Gasset-

The political stage of José Ortega y Gasset

Ortega y Gasset was elected deputy during the Second Republic. Then, together with Marañón and Pérez de Ayala, he founded the Agrupación al Servicio de la República. He held that position with great hope until, little by little, he began to feel certain discrepancies with the wrong course — carried away by the Republic, in his opinion. However, everything changed in 1936 with the Civil War.

He had no choice but to live in exile. He spent about 10 years as a refugee in France, the Netherlands, Argentina, and Portugal. His return in 1945 allowed him to meet many like-minded intellectuals he continued working with. Thus, he founded the Humanities Institute in 1948 with Julián Marías.

From that moment on, his figure once again stood out among the Spanish cultural scene. He was a professor of several philosophy students and reflected his liberal ideas in various newspapers, books, and essays. He founded the newspaper El Sol (1917), the magazine España (1915), and Revista de Occidente (1923).

Likewise, José Ortega y Gasset was a figure of undeniable relevance that later inspired the generation of ’27. His wake as a regenerationist intellectual, personal ideology, and philosophical principles, crossed borders that reached Europe and Latin America. He died in 1955 at the age of 72 at his home in Madrid.

José Ortega y Gasset’s masterpiece, The Revolt of the Masses

José Ortega y Gasset was a part of three basic trends. The first was Noucentisme, a movement for cultural renewal. The second was perspectivism (a concept established by Friedrich Nietzsche that extolled the idea that there’s no single truth and each person has a different perspective).

The third approach, crucial to his work, was an idea he developed. It was about vitalism, an idea of where to assume the inevitable interrelation between a person and their reality. These pillars were key when writing one of his most representative works, The Revolt of the Masses in 1930.

The danger of a community that doesn’t reason

A structuring aspect you can appreciate on each page of The Revolt of the Masses is the end of conservatism and the beginning of something new that isn’t always as positive as you may think. In the regeneration that modern life brings, there are a series of challenges that also arise. Through them, the person, a modern and apparently liberated citizen, has no choice but to understand.

- First of all, the concept of “mass” has nothing to do with the term used by Marxists.

- The mass, for Ortega y Gasset, is about individualization. That is, they’re no longer isolated or individual figures. Instead, they’re a community often conditioned by their emotions rather than by reasoning.

- Those masses already appear in the new democracies of the time. Therefore, even if you leave authoritarianism behind, other dangers arise. Because collectives can also align with other figures in public life.

- In the book, Gasset made reference to the acts of vandalism that occurred in France in the late 30s. Thousands of young people there took to the streets and started burning cars to vent their anger guided or motivated by other people who sought to “ignite the masses”.

A very present legacy

The Revolt of the Masses is a key work of philosopher José Ortega y Gasset from which, as you can see, emanate multiple ideas that are still relevant. In fact, they’re quite relevant and invite you to reflect on something that he wanted to convey to his readers: you’re threatening democracy when you act as gregarious groups.

Humans are a part of a historical and social context there’s no escape from. However, you must separate yourself from the masses that act on instinct. Thus, you must act as an individual, responsible for yourself and always attentive to those who dare to veto their own freedoms.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Hegel, G. W. F., Gaos, J., & Ortega y Gasset, J. (2008). Lecciones sobre la filosofía de la historia universal. Alianza.

- Gracia, Jordi (2014) José Ortega y Gasset. Taurus

- Ortega y Gasset, José. (2004) Obras completas, Vol. I. Ed. Taurus

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.