Géza Róheim and the Fusion of Psychoanalysis and Anthropology

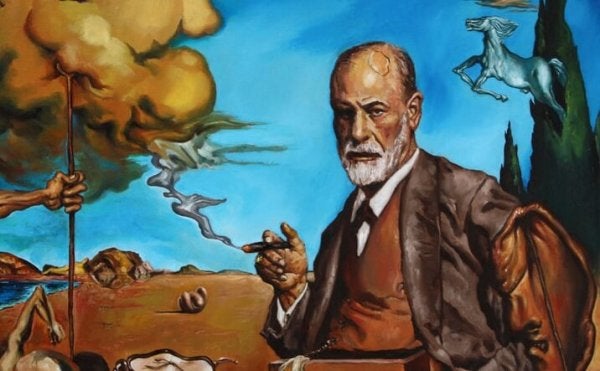

Although the name Géza Róheim isn’t as well-known as others in the world of psychoanalysis, he was one of the most brilliant minds in the field. In fact, Sigmund Freud himself said that the researcher was one of the few who managed to broaden the scope of psychoanalysis and culture, beyond what he had proposed in his seminal work, Totem and Taboo.

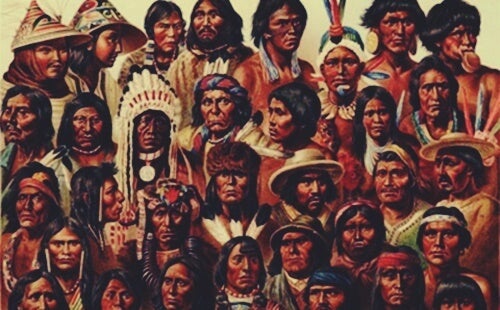

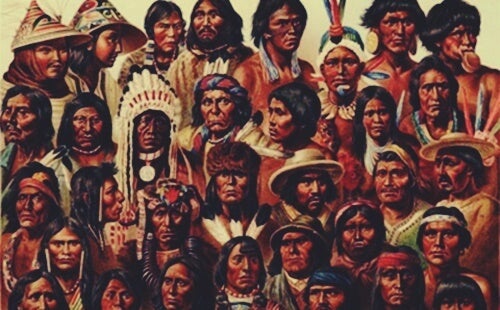

Many consider Géza Róheim to be the father of psychoanalytic anthropology. He’s also admired for the meticulous records he made of his fieldwork with indigenous communities in Australia and North America. The same precision and intensity gave him his privileged place in the history of psychoanalysis.

Géza Róheim’s seminal work is titled Psychoanalysis and Anthropology: Culture, Personality, and the Unconscious. In it, he applied Freudian principles to concepts of cultural comprehension, something that many of his contemporaries thought was wrong. Nevertheless, over time, his approach has quieted the naysayers.

Géza Róheim’s beginnings

Géza Róheim was born in Budapest, Hungary in September of 1891. Unlike many pioneers in psychoanalysis, Róheim had a very happy childhood. He was the only child of Jewish merchants who raised him with love and affection. His grandfather doted on him and shared with him his interest in myths and popular legends.

When Géza Róheim was only eight years old, he read The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper. This approximation of primitive cultures fascinated him from the very beginning. From then on, he read everything he could find on the subject and quickly became an expert.

Róheim was a happy and charismatic person who divided his time between books about mythology and ethnography and his love for good cooking and sports. In 1914, he graduated with a degree in geography. Later, he continued his studies in Leipzig and Berlin, Germany. That’s where he first came into contact with psychoanalysis through the work of Otto Rank.

A new approach

Géza Róheim said that his discovery of Freud was an enlightening experience. He felt like all of his knowledge was separate and unfocused, and psychoanalysis was the theoretical structure that gave order and meaning to a lot of his observations and knowledge.

Róheim started studying psychoanalysis, first with Sandor Ferenczi and later with Wilma Kovacs. In the beginning, the work of Melanie Klein was very influential for him. Later, he dove deeper into Freud’s work and concepts and moved more towards classical psychoanalysis. He met Freud in person in 1918.

From then on, Róheim’s work focused on the psychoanalytic interpretation of cultural and social phenomena. His work was not purely analytic or theoretical. Instead, it was based on the time he spent with indigenous communities.

The work of Géza Róheim

Géza Róheim published several far-reaching books, such as The Riddle of the Sphinx, Magic and Schizophrenia, and The Gates of the Dream. He wrote in Hungarian, and his books were later translated into English and French. Only a small portion of his work is available in Spanish.

Róheim proposed that the myths and legends of indigenous peoples have a structure similar to that of individuals’ dreams. From that perspective, these cultural productions could be analyzed the same as a dream. He also presented evidence that Freud’s concept of the Oedipus complex is universal. In other words, it exists across time and culture.

At the time, Róheim was one of the biggest detractors of famous anthropologists such as Bronislaw Malinowski and Margaret Mead. He questioned their interest in showing the unique aspects of each culture, which led people to believe that they were vastly different from one another. Róheim believed the opposite, that universal elements were far more important than circumstantial specificities. Géza Róheim died in the United States in 1953, two months after his beloved wife passed away.

Although the name Géza Róheim isn’t as well-known as others in the world of psychoanalysis, he was one of the most brilliant minds in the field. In fact, Sigmund Freud himself said that the researcher was one of the few who managed to broaden the scope of psychoanalysis and culture, beyond what he had proposed in his seminal work, Totem and Taboo.

Many consider Géza Róheim to be the father of psychoanalytic anthropology. He’s also admired for the meticulous records he made of his fieldwork with indigenous communities in Australia and North America. The same precision and intensity gave him his privileged place in the history of psychoanalysis.

Géza Róheim’s seminal work is titled Psychoanalysis and Anthropology: Culture, Personality, and the Unconscious. In it, he applied Freudian principles to concepts of cultural comprehension, something that many of his contemporaries thought was wrong. Nevertheless, over time, his approach has quieted the naysayers.

Géza Róheim’s beginnings

Géza Róheim was born in Budapest, Hungary in September of 1891. Unlike many pioneers in psychoanalysis, Róheim had a very happy childhood. He was the only child of Jewish merchants who raised him with love and affection. His grandfather doted on him and shared with him his interest in myths and popular legends.

When Géza Róheim was only eight years old, he read The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper. This approximation of primitive cultures fascinated him from the very beginning. From then on, he read everything he could find on the subject and quickly became an expert.

Róheim was a happy and charismatic person who divided his time between books about mythology and ethnography and his love for good cooking and sports. In 1914, he graduated with a degree in geography. Later, he continued his studies in Leipzig and Berlin, Germany. That’s where he first came into contact with psychoanalysis through the work of Otto Rank.

A new approach

Géza Róheim said that his discovery of Freud was an enlightening experience. He felt like all of his knowledge was separate and unfocused, and psychoanalysis was the theoretical structure that gave order and meaning to a lot of his observations and knowledge.

Róheim started studying psychoanalysis, first with Sandor Ferenczi and later with Wilma Kovacs. In the beginning, the work of Melanie Klein was very influential for him. Later, he dove deeper into Freud’s work and concepts and moved more towards classical psychoanalysis. He met Freud in person in 1918.

From then on, Róheim’s work focused on the psychoanalytic interpretation of cultural and social phenomena. His work was not purely analytic or theoretical. Instead, it was based on the time he spent with indigenous communities.

The work of Géza Róheim

Géza Róheim published several far-reaching books, such as The Riddle of the Sphinx, Magic and Schizophrenia, and The Gates of the Dream. He wrote in Hungarian, and his books were later translated into English and French. Only a small portion of his work is available in Spanish.

Róheim proposed that the myths and legends of indigenous peoples have a structure similar to that of individuals’ dreams. From that perspective, these cultural productions could be analyzed the same as a dream. He also presented evidence that Freud’s concept of the Oedipus complex is universal. In other words, it exists across time and culture.

At the time, Róheim was one of the biggest detractors of famous anthropologists such as Bronislaw Malinowski and Margaret Mead. He questioned their interest in showing the unique aspects of each culture, which led people to believe that they were vastly different from one another. Róheim believed the opposite, that universal elements were far more important than circumstantial specificities. Géza Róheim died in the United States in 1953, two months after his beloved wife passed away.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

Romero, A., & Visbal, A. (1999). Relaciones científicas: acerca de las conexiones de la Psicología y otras ciencias. Discernimiento, 11.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.