Anterograde Amnesia: An Inability to Learn New Information

Written and verified by the psychologist Gema Sánchez Cuevas

Remembering a phone number off the top of your head, recognizing someone you know on the street and remembering their name, remembering where you went on vacation last summer… All of these functions are part of a basic yet very important psychological process: memory.

But when you can’t remember events from the past or learn new information, your memory might be damaged. You may even have anterograde amnesia.

Today, the role of memory is valued because of how much time it saves when it’s working well. People with a “good memory” can solve problems more quickly if they’ve already solved it before. After all, they’ve already practiced the process they would need to find a solution.

The same can be said for abilities like swimming, typing quickly, and riding a bicycle. Once you learn how to do it, you don’t forget even if you haven’t done it for a long time. They might get a little rusty if you’re out of practice, but soon you’ll get back to the level you were at before.

Seen from this angle, human memory seems to be responsible for a wide range of functions. However, it doesn’t always function at the level we would like. Certain memory failures, like forgetting where you put your keys, don’t seem too serious. Other times it can be more concerning, like when you can’t remember who you were just talking to.

What can memory do?

Memory allows us to learn, organize, and consolidate information and past events. It’s closely linked to attention, another basic psychological process. The process has three stages: encoding, storage, and recall. Amnesia disrupts memory.

We can think of memory as a three-part psychological process by which we encode information, store it in the brain, and recall it when we need it. The most important part is that the information we learn be recalled when it’s not right in front of us. Sometimes we recall things quickly and precisely, and other times with more difficulty.

Studies on memory in the fields of cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience indicate that the brain has multiple memory systems. In turn, each of them has its own characteristics, functions, and processes.

Memory can be defined as a three-part psychological process by which we encode information, store it in the brain, and recall it when we need it.

An inability to access memories or learn new things

Amnesia is diagnosed when the person presents serious memory problems. These may include an inability to store new information or recall previously recorded information.

Organic amnesia is the result of physical brain damage caused by illness, injury, or even substance abuse. On the other hand, dissociative amnesia is due to psychological factors, like repression and other defense mechanisms.

In addition, there have been cases of spontaneous amnesia, such as transient global amnesia. This one is a sudden loss of memory for no apparent reason. It happens more often in elderly men and tends to last for less than 20 hours.

Amnesia can also be classified according to the type of memories that the person is unable to recall or form. Anterograde amnesia is the inability to form new memories. Retrograde amnesia is the inability to recall past memories that a person used to be able to access.

People with anterograde amnesia can remember things that happened in their youth. But they can’t learn or remember things that happened after the onset of the injury that caused the amnesia.

Korsakoff’s syndrome

Of all the organic types of amnesia, Korsakoff’s syndrome is the most common. It is caused by a thiamine deficiency in the brain generally due to chronic alcoholism. It was named after Sergei Korsakoff, the man who discovered it.

Korsakoff’s syndrome is characterized by an acute state of mental confusion and spatiotemporal disorientation. When it’s chronic, the confused state is prolonged.

Often, the onset of Korsakoff’s syndrome follows an acute episode of Wernicke’s disease, or Wernicke’s encephalopathy. When both occur together, it is called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

The main symptoms of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome include:

- ataxia (lack of coordination)

- ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of the ocular muscles)

- polyneuropathy (pain and weakness in the same areas of the body on both sides)

People with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome also suffer from:

- disorientation in time, place, and person

- the inability to recognize family members

- apathy

- attention deficits

- the inability to maintain a coherent conversation

Retrograde amnesia: forgetting the past

A severe brain injury, whether from a fall, an accident, or an electrical shock, can produce retrograde amnesia. Retrograde amnesia is defined as the inability to remember past events. In many cases, the amnesia goes away, and the person gradually recovers their memory. In the best cases, it comes back completely.

Retrograde amnesia generally “erases” memories just a few minutes before the injury. If the blow is really strong, it can affect memories from months or even years before.

Anterograde amnesia: living with no future

Some injuries produce a global, permanent memory deficit without any other reduction in intellectual ability. In these cases, the person has no problems with language, perception, or attention. In addition, they retain the skills they had before the injury.

People with anterograde amnesia have incredible difficulty retaining new information, but they can maintain a conversation. Their operative memory functions normally, but a few minutes later they can’t remember what just happened.

Therefore, people with anterograde amnesia can’t learn new things (or have an extremely hard time with it). Sometimes they can’t even remember information from the past. It’s almost like living perpetually in the present. The past hardly exists, and they can’t make plans for the future because they’ll forget.

However, they can learn new skills, albeit much more slowly than the general population.

Associated areas of the brain

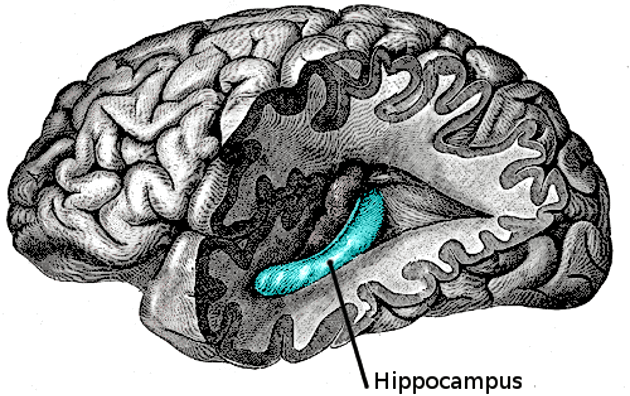

One of the main challenges of modern day neuroscience is to figure out which areas of the brain play a role in anterograde amnesia. In general, they believe the brain damage that causes it occurs in the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe.

These brain regions act as a passageway where events and facts are stored provisionally until they can be stored more permanently in the frontal lobe. Think of the hippocampus like a storage space for short-term memory.

If it can’t store information correctly, it will be impossible for the information to reach the frontal lobe. This means the brain can’t form long-term memories. In cases of partial amnesia, the memories might form but have very few real details.

However, even though the hippocampus might seem like the most important region involved in anterograde amnesia, recent studies suggest that other brain structures play a role too. Specifically, damage to the basal forebrain seems to also interrupt the process of memory formation.

This area is in charge of producing acetylcholine, a very important substance for memory function, initiating and modulating the processes involved. The most common type of brain damage to the basal forebrain is an aneurysm, which is frequently associated with anterograde amnesia.

Finally, the relationship between amnesia and Korsakoff’s syndrome has pointed to a third region that may play a role in the development of anterograde amnesia. The diencephalon is a region that suffers damage due to Korsakoff’s syndrome. Recently, researchers have begun studying the involvement of the diencephalon in amnesia.

Signs of anterograde amnesia

The clearest sign of anterograde amnesia is low performance on traditional memory and recognition tests. A few minutes after someone presents them with a list of 15-20 words, people with anterograde amnesia can only remember a few.

In addition, most forget words at the beginning or middle of the list, but can remember ones at the end at an almost normal level. The same thing happens with conversations, movies, and TV shows. Everyday activities become hard: they forget where they’ve left things, what they’ve done, and who they’ve seen.

Therefore, it can cause problems living with other people, since it’s hard for them to hold a conversation or remember what they talked about with someone on previous occasions. They give off the impression that they’re not really in the present.

Everyday activities become problematic: they forget where they’ve left things, what they’ve done, and who they’ve seen.

They talk about people and events from the past as if they were happening now. They can’t make plans for the future because they don’t even know what they’re going to do tomorrow. Maybe that’s why they lack the warmth or intimacy that people normally display when they talk about memories from the past and their hopes for the future.

At the same time, their memory problems can obviously cause huge issues in their daily lives. At home, they might need constant care or supervision. After all, they can’t remember things like taking their medication, and can’t successfully do things that involve multiple steps.

However, they can learn to do other things like walk short distances, from home to a nearby store for example. It seems like they retain a lot of their knowledge, just like people with retrograde amnesia.

Can they learn new things?

Gabrieli, Cohen and Corkin (1983) tried to answer this question with their patient H.M. They asked him to define words and phrases that people had only started to use when he already had amnesia. He didn’t have much success, although he did know what rock and roll was. They also tried to teach him the meaning of unfamiliar words. Despite lengthy training, the only thing he could do was match words to their definitions.

There have been other cases. A 10-year-old boy with severe anterograde amnesia due to anoxia (lack of oxygen) couldn’t improve his reading level after the incident. He also did pretty poorly on different semantic memory tests. However, he was able to learn to play computer games just as easily as his peers (Wood, Ebert and Kinsbourne 1982).

How can we explain the preservation of certain functions?

Some theories propose the idea of multiple memory systems. While the one responsible for normal functioning on certain tests might remain intact with amnesia, others suffer damage. That’s why performance on different tests varies in comparison with the general population.

The distinction between episodic memory and semantic memory (Tulving 1972) has led some authors to suggest that with amnesia, semantic memory functions normally, which would explain why certain linguistic functions remain intact. Damage to the episodic memory would explain the failure of recall and recognition functions.

People with amnesia seem to have unimpaired linguistic function, and they perform well on tests involving past knowledge. This means that people acquire all the concepts and rules needed to complete these tests successfully very early in life.

Conclusion

Setting aside theories about how people develop amnesia, the main takeaway to remember is that anterograde amnesia is a selective memory deficit as a consequence of brain damage. The biggest problem these people have is extreme difficulty storing new information. They can’t remember new things and have a lot of trouble learning.

However, anterograde amnesia does not affect the memory of past information. All the information stored before the damage occurred is fine, and the person can remember it without problems. But it’s also important to remember that characteristics of anterograde amnesia vary case by case.

References:

Belloch, A., Sandín, B. and Ramos, F. (Eds.) (1995). Manual de Psicopatología (2 vols.). Madrid: McGraw Hill.

Freedman, A.M., Kaplan, H.I. and Sadock, B.J. (Eds.) (1983). Tratado de Psiquiatría. (2 vols.). Barcelona: Salvat. (Orig.: 1980).

Remembering a phone number off the top of your head, recognizing someone you know on the street and remembering their name, remembering where you went on vacation last summer… All of these functions are part of a basic yet very important psychological process: memory.

But when you can’t remember events from the past or learn new information, your memory might be damaged. You may even have anterograde amnesia.

Today, the role of memory is valued because of how much time it saves when it’s working well. People with a “good memory” can solve problems more quickly if they’ve already solved it before. After all, they’ve already practiced the process they would need to find a solution.

The same can be said for abilities like swimming, typing quickly, and riding a bicycle. Once you learn how to do it, you don’t forget even if you haven’t done it for a long time. They might get a little rusty if you’re out of practice, but soon you’ll get back to the level you were at before.

Seen from this angle, human memory seems to be responsible for a wide range of functions. However, it doesn’t always function at the level we would like. Certain memory failures, like forgetting where you put your keys, don’t seem too serious. Other times it can be more concerning, like when you can’t remember who you were just talking to.

What can memory do?

Memory allows us to learn, organize, and consolidate information and past events. It’s closely linked to attention, another basic psychological process. The process has three stages: encoding, storage, and recall. Amnesia disrupts memory.

We can think of memory as a three-part psychological process by which we encode information, store it in the brain, and recall it when we need it. The most important part is that the information we learn be recalled when it’s not right in front of us. Sometimes we recall things quickly and precisely, and other times with more difficulty.

Studies on memory in the fields of cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience indicate that the brain has multiple memory systems. In turn, each of them has its own characteristics, functions, and processes.

Memory can be defined as a three-part psychological process by which we encode information, store it in the brain, and recall it when we need it.

An inability to access memories or learn new things

Amnesia is diagnosed when the person presents serious memory problems. These may include an inability to store new information or recall previously recorded information.

Organic amnesia is the result of physical brain damage caused by illness, injury, or even substance abuse. On the other hand, dissociative amnesia is due to psychological factors, like repression and other defense mechanisms.

In addition, there have been cases of spontaneous amnesia, such as transient global amnesia. This one is a sudden loss of memory for no apparent reason. It happens more often in elderly men and tends to last for less than 20 hours.

Amnesia can also be classified according to the type of memories that the person is unable to recall or form. Anterograde amnesia is the inability to form new memories. Retrograde amnesia is the inability to recall past memories that a person used to be able to access.

People with anterograde amnesia can remember things that happened in their youth. But they can’t learn or remember things that happened after the onset of the injury that caused the amnesia.

Korsakoff’s syndrome

Of all the organic types of amnesia, Korsakoff’s syndrome is the most common. It is caused by a thiamine deficiency in the brain generally due to chronic alcoholism. It was named after Sergei Korsakoff, the man who discovered it.

Korsakoff’s syndrome is characterized by an acute state of mental confusion and spatiotemporal disorientation. When it’s chronic, the confused state is prolonged.

Often, the onset of Korsakoff’s syndrome follows an acute episode of Wernicke’s disease, or Wernicke’s encephalopathy. When both occur together, it is called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

The main symptoms of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome include:

- ataxia (lack of coordination)

- ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of the ocular muscles)

- polyneuropathy (pain and weakness in the same areas of the body on both sides)

People with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome also suffer from:

- disorientation in time, place, and person

- the inability to recognize family members

- apathy

- attention deficits

- the inability to maintain a coherent conversation

Retrograde amnesia: forgetting the past

A severe brain injury, whether from a fall, an accident, or an electrical shock, can produce retrograde amnesia. Retrograde amnesia is defined as the inability to remember past events. In many cases, the amnesia goes away, and the person gradually recovers their memory. In the best cases, it comes back completely.

Retrograde amnesia generally “erases” memories just a few minutes before the injury. If the blow is really strong, it can affect memories from months or even years before.

Anterograde amnesia: living with no future

Some injuries produce a global, permanent memory deficit without any other reduction in intellectual ability. In these cases, the person has no problems with language, perception, or attention. In addition, they retain the skills they had before the injury.

People with anterograde amnesia have incredible difficulty retaining new information, but they can maintain a conversation. Their operative memory functions normally, but a few minutes later they can’t remember what just happened.

Therefore, people with anterograde amnesia can’t learn new things (or have an extremely hard time with it). Sometimes they can’t even remember information from the past. It’s almost like living perpetually in the present. The past hardly exists, and they can’t make plans for the future because they’ll forget.

However, they can learn new skills, albeit much more slowly than the general population.

Associated areas of the brain

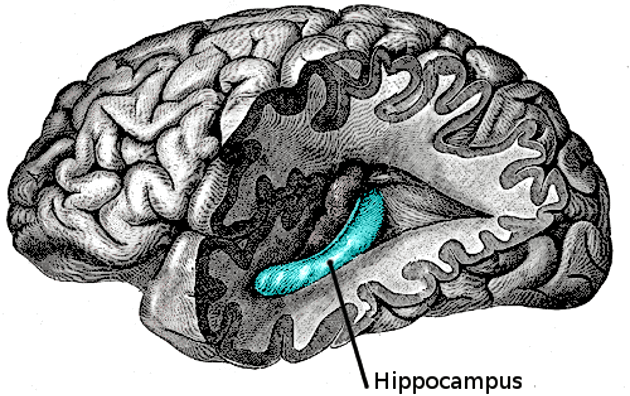

One of the main challenges of modern day neuroscience is to figure out which areas of the brain play a role in anterograde amnesia. In general, they believe the brain damage that causes it occurs in the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe.

These brain regions act as a passageway where events and facts are stored provisionally until they can be stored more permanently in the frontal lobe. Think of the hippocampus like a storage space for short-term memory.

If it can’t store information correctly, it will be impossible for the information to reach the frontal lobe. This means the brain can’t form long-term memories. In cases of partial amnesia, the memories might form but have very few real details.

However, even though the hippocampus might seem like the most important region involved in anterograde amnesia, recent studies suggest that other brain structures play a role too. Specifically, damage to the basal forebrain seems to also interrupt the process of memory formation.

This area is in charge of producing acetylcholine, a very important substance for memory function, initiating and modulating the processes involved. The most common type of brain damage to the basal forebrain is an aneurysm, which is frequently associated with anterograde amnesia.

Finally, the relationship between amnesia and Korsakoff’s syndrome has pointed to a third region that may play a role in the development of anterograde amnesia. The diencephalon is a region that suffers damage due to Korsakoff’s syndrome. Recently, researchers have begun studying the involvement of the diencephalon in amnesia.

Signs of anterograde amnesia

The clearest sign of anterograde amnesia is low performance on traditional memory and recognition tests. A few minutes after someone presents them with a list of 15-20 words, people with anterograde amnesia can only remember a few.

In addition, most forget words at the beginning or middle of the list, but can remember ones at the end at an almost normal level. The same thing happens with conversations, movies, and TV shows. Everyday activities become hard: they forget where they’ve left things, what they’ve done, and who they’ve seen.

Therefore, it can cause problems living with other people, since it’s hard for them to hold a conversation or remember what they talked about with someone on previous occasions. They give off the impression that they’re not really in the present.

Everyday activities become problematic: they forget where they’ve left things, what they’ve done, and who they’ve seen.

They talk about people and events from the past as if they were happening now. They can’t make plans for the future because they don’t even know what they’re going to do tomorrow. Maybe that’s why they lack the warmth or intimacy that people normally display when they talk about memories from the past and their hopes for the future.

At the same time, their memory problems can obviously cause huge issues in their daily lives. At home, they might need constant care or supervision. After all, they can’t remember things like taking their medication, and can’t successfully do things that involve multiple steps.

However, they can learn to do other things like walk short distances, from home to a nearby store for example. It seems like they retain a lot of their knowledge, just like people with retrograde amnesia.

Can they learn new things?

Gabrieli, Cohen and Corkin (1983) tried to answer this question with their patient H.M. They asked him to define words and phrases that people had only started to use when he already had amnesia. He didn’t have much success, although he did know what rock and roll was. They also tried to teach him the meaning of unfamiliar words. Despite lengthy training, the only thing he could do was match words to their definitions.

There have been other cases. A 10-year-old boy with severe anterograde amnesia due to anoxia (lack of oxygen) couldn’t improve his reading level after the incident. He also did pretty poorly on different semantic memory tests. However, he was able to learn to play computer games just as easily as his peers (Wood, Ebert and Kinsbourne 1982).

How can we explain the preservation of certain functions?

Some theories propose the idea of multiple memory systems. While the one responsible for normal functioning on certain tests might remain intact with amnesia, others suffer damage. That’s why performance on different tests varies in comparison with the general population.

The distinction between episodic memory and semantic memory (Tulving 1972) has led some authors to suggest that with amnesia, semantic memory functions normally, which would explain why certain linguistic functions remain intact. Damage to the episodic memory would explain the failure of recall and recognition functions.

People with amnesia seem to have unimpaired linguistic function, and they perform well on tests involving past knowledge. This means that people acquire all the concepts and rules needed to complete these tests successfully very early in life.

Conclusion

Setting aside theories about how people develop amnesia, the main takeaway to remember is that anterograde amnesia is a selective memory deficit as a consequence of brain damage. The biggest problem these people have is extreme difficulty storing new information. They can’t remember new things and have a lot of trouble learning.

However, anterograde amnesia does not affect the memory of past information. All the information stored before the damage occurred is fine, and the person can remember it without problems. But it’s also important to remember that characteristics of anterograde amnesia vary case by case.

References:

Belloch, A., Sandín, B. and Ramos, F. (Eds.) (1995). Manual de Psicopatología (2 vols.). Madrid: McGraw Hill.

Freedman, A.M., Kaplan, H.I. and Sadock, B.J. (Eds.) (1983). Tratado de Psiquiatría. (2 vols.). Barcelona: Salvat. (Orig.: 1980).

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.