Alejandra Pizarnik, Biography of an Accursed Writer

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

Some say Alejandra Pizarnik was an accursed writer born with darkness in her soul. They nourished her rebellion, dramatic personality, and passion. In fact, she took advantage of them and came up with some unique poetry. She wrote about cages, eyes, heavy rocks, and introduced the world to Elizabeth Báthory, The Bloody Countess. Also, she navigated madness in a dreamlike state and left exceptional work behind.

She was the kind of woman who always felt like an outsider. Her own complexes and weight gains really bummed her down. Her childhood was a combination of disillusionment, fear, and emptiness. (Heaven has the color of dead childhood, she once wrote). Scholars also said she did a little bit of everything: journalism, philosophy, painting… but only poetry and amphetamines relieved her anxiety.

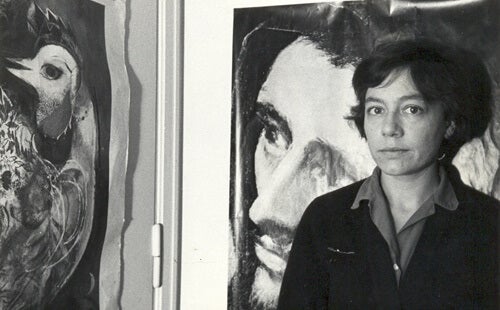

Alejandra Pizarnik, who became popular in Paris, permeated her mind and heart with the final stage of surrealism. She became friends with André Breton, Georges Bataille, and Yves Bonnefoy. Above all, she met someone who was key in her life and also in her career. His name was Octavio Paz, another notable poet.

The last accursed writer

No one explored suffering and madness like she did. She was an unfolded woman who claimed to have dead twins within her: past Alexandra and present Alexandra. They never dared to live. She took her own life in 1972, at the age of 36. However, it was an announced end, because she spent her entire existence tiptoeing around it. Deep in an abyss, she sought an out on many occasions. Until in the end, she found liberation for her torments and darkness.

To this day, Alejandra Pizarnik is still known as the last accursed poet in America. To read her work is to immerse yourself in equal parts of romanticism, surrealism, Gothic, and also in psychoanalysis. Her’s is a singular universe very few people are indifferent to.

“I don’t know about birds nor do I know the history of fire. But I believe that my solitude should have wings.”

-Alejandra Pizarnik-

Alejandra Pizarnik, a life torn between enlightenment and darkness

Being born in Avellaneda, a suburb of Buenos Aires, wasn’t probably easy for Alejandra Pizarnik. Her family was of Russian-Jewish origin, and they endured the pain of having left their native country. They were marked by the Holocaust, by the horror and personal losses they experienced during the war.

That shadow must’ve imprinted on her early. It was an inherited wound that was further aggravated by a body she didn’t like. Also, by the rejection of a mother who valued her sister more and for the state of her health. She had asthma and her stuttering limited much of her childhood. All this made her perceive herself as an outsider early on. Within a body in which she couldn’t find herself.

Literature and philosophy were her safe space as a child. That literary residue very soon aroused her need for writing and also opened the door to the particular brand of rebellion that always characterized her. As a teenager, she was known for the way she dressed and overall appearance.

Her mind was a witness to her poetic charisma before she reached college. Likewise, her need to take refuge found it and it had nothing to do with her books or writing. Her concern about gaining weight and the rejection of her own body led to her consumption of barbiturates and amphetamines.

A life of unsuccessful searches

In 1954, Alejandra Pizarnik began a degree in philosophy and letters at the University of Buenos Aires. She didn’t graduate. Later on, she delved into journalism but she didn’t like it either. Next, she began artistic training with the surrealist painter Batlle Planas. Her country was too small for her, and her eagerness to find a meaning and a channel for self-realization led her to spend a few years in Paris.

Thus, between 1960 and 1964, she lived a gratifying stage in which she began to work as a translator and wrote literary critiques for various magazines. This is when she met two people who became important to her. They were Julio Cortázar and Octavio Paz, the Mexican poet. The latter wrote the prologue to her book of poems Diana’s Tree (1962).

In 1965, the last accursed writer continued with her literary work, already in Argentina. The cultural community of that era appreciated her work and she obtained two scholarships, the Guggenheim and the Fullbright. However, she didn’t take advantage of them. Mainly due to her depressive crises, discouragement, and search for meaning that was never fruitful.

Her friends later said that, after returning from Paris, this cursed writer began to protect herself behind a self-made barrier. She attempted suicide after her father’s death. Then, her dependence on sleeping pills became more intense, almost desperate. In fact, in 1972, she was admitted to a psychiatric hospital after an intense depressive episode.

On September 25, taking advantage of a hospital leave, she took 50 secobarbital pills. There was no turning back, Alejandra finally managed to kill herself. She was 36 years old.

The work of an accursed writer

Much of Alejandra Pizarnik’s work was created around two spheres: her childhood in Buenos Aires and her fascination with death. Also, something you must take into account is a large part of her works are available thanks to Julio Cortázar and, above all, to Aurora Bernárdez, his first wife.

This is because Alejandra’s family, rather puritan and disgusted by her taste and literary style, nearly destroyed her notebooks. Also, the cultural repression of Argentina made it harder to conserve them. It was for this reason that someone took her diaries to Paris. Once they arrived, the Cortázars guarded them and then placed them under the care of Columbia University.

Her lyrical work is included in seven poetry books: The Most Alien Land (1955), The Last Innocence (1956), The Last innocence/The Lost Adventures (1958), Diana’s Tree (1962), Works and Nights (1965), Extracting the Madness Stone (1968), and A Musical Hell (1971).

Later, someone published her latest poems posthumously. Among them, the novels Pernambuco’s Buccaneer and Hilda, the Polygraph. Her most famous striking story, The Bloody Countess, is also worth mentioning.

Her style

Alejandra Pizarnik wrote frantically from the age of 15. She did it religiously because it was her only way of expressing herself in a world in which she felt like an outsider. Her poetry is full of symbols, silences, madness, the shadow of death, and delusions, among others. Poetry, according to her, was the place where the impossible becomes possible.

It was also the voice of feminism; her words had a sort of subversive beauty, in which only truths fit. Through it, she criticized labels, conventions, and the duty to be like everyone else. She was a woman who was unable to adjust to any kind of expectations.

Hence the boredom, the drowsiness, and the prevailing melancholy that made her heart collapsed and permeated her poems. Alejandra Pizarnik was an accursed writer. A great one who continues to overwhelm people through her verses and distant yet emphatic voice.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- PIÑA, Cristina (2005) Alejandra Pizarnik. Una biografía, Buenos Aires, Corregidor

- VENTI, Patricia (2008) La escritura invisible: el discurso autobiográfico en Alejandra Pizarnik, Barcelona, Anthropos

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.