Adrenocorticotropic Hormone: Characteristics and Functions

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is a hormone produced in the pituitary gland. This is the main endocrine gland in vertebrates. The hormones it secretes control the functioning of almost all other endocrine glands in the body (1).

Thus, ACTH is a corticotropic cell. These mainly produce adrenocorticotropic hormones that they place in the center. We’ll detail the characteristics of this particular hormone below.

Synthesis of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

This hormone is synthesized from a protein called proopiomelanocortin (POMC). This precursor protein is composed of 266 amino acids, and ACTH is composed of 39 amino acids. In addition, PMOC also generates other peptides, such as:

- Lipotropin

- Endorphin

- Met-encephaline

- Melanocyte stimulating hormone

- Mid-lobe protein similar to corticotropin (CLIP)

Adrenocorticotrophin secretion

As we mentioned above, the secretion of the adrenocorticotropic hormone is pulsatile. This means that it follows a characteristic circadian rhythm, reaching its maximum rhythm at 6:00 a.m., and its minimum at midnight.

Thanks to the secretion of ACTH, suprarenal glucocorticoids are secreted, following a parallel daytime pattern. The biological half-life of ACTH in the circulation is less than ten minutes.

Modulators of ACTH synthesis and/or secretion

Stimulators

- CRH (main modulator)

- TNF (tumor necrosis factor)

- IL-1 (interleukin-1)

- CKK (cholecystokinin)

- VIP (vasoactive intestinal peptide)

- Alpha-adrenergic stimuli

- Acetylcholine

- Serotonin

Inhibitors

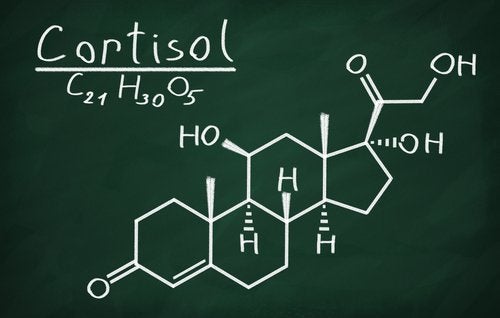

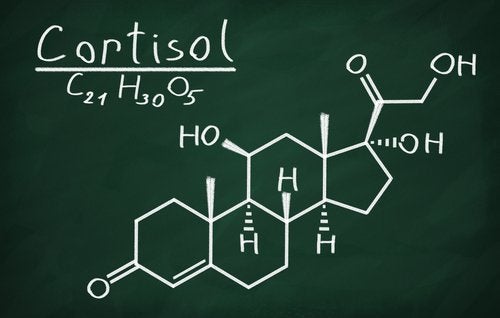

- Cortisol (main modulator)

- GABA

- Endorphins

- Encephalins

- Activin

- Galanin

- ANP (atrial natriuretic peptide)

- Substance P

Mechanism of action of adrenocorticotropic hormone

ACTH acts through a membrane receptor. This receptor is called the melanocortin receptor 2, a receptor coupled to G proteins. The second biological messenger is cAMP.

Action

ACTH acts in the following way:

- It preserves the homeostasis of metabolism and controls the endocrine reaction to stress.

- It induces steroidogenesis. This is a set of metabolic reactions that mainly ensure the synthesis of steroid hormones in a certain organ or tissue (corticoids, androgens, and, to a lesser extent, mineralocorticoids).

- It stimulates skin pigmentation, which is determined by the amount of melanin in the skin. This is because its molecule contains the sequence of melanocyte-stimulating hormones (MSH).

- It also produces a certain degree of lipolysis: the breakdown of food lipids into fatty acids during digestion.

Frequently, the inhibition of ACTH and the adrenal axis occurs due to the use of steroids. For example, in asthma, collagenopathies, and hematological diseases (1).

ACTH-related diseases

Cushing’s syndrome

This syndrome includes a series of clinical and biochemical abnormalities resulting from chronic exposure to excess cortisol produced by the adrenal cortex. Between 80 and 85% of this syndrome is caused by a pituitary adenoma that produces ACTH (3).

The differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome constitutes one of the greatest challenges in endocrinology. While the clinical manifestations are obvious in many cases, they can be very subtle in others. Weight gain with central fat redistribution affecting the face, neck, trunk, and abdomen is one of the most common clinical findings (4).

Thus, other important clinical data are the presence of facial plethora, hirsutism, acne, menstrual disorders, hypertension, proximal muscle weakness, stretch marks, carbohydrate intolerance, or diabetes (5).

Addison’s disease (6)

Addison’s disease is a syndrome characterized by a lack of glucose and/or mineralocorticoids. In this case, a deficient production of ACTH may occur, thus leading to a decrease in the production of glucocorticoids (secondary hypoadrenocorticism).

Secondary hypoadrenocorticism can be natural or iatrogenic. The natural form is due to the absence of normal adrenal stimulation by CRH or ACTH and denotes primary pituitary or hypothalamic failure. Thus, most of these cases are the result of inflammation, tumors, trauma, or hypothalamic or pituitary birth defects.

The iatrogenic form is the most common form of secondary hypoadrenocorticism in veterinary medicine. It occurs due to the exogenous administration of glucocorticoids, which suppress the normal production of pituitary ACTH. As a result, it promotes bilateral adrenal atrophy.

Addison’s disease is a slow and progressive process. It’s caused by the insufficient supply of adrenocortical hormones for the body’s normal requirements. Thus, they have their origin in the bilateral destruction of the adrenal cortex. In addition, the symptomatology doesn’t begin to appear until the loss of 90 percent or more of the adrenal tissue (7).

Thus, ACTH is a key hormone in the correct functioning of the nervous system. In fact, its malfunctioning involves some illnesses such as those we’ve seen, in addition to other hormonal disorders. Scientists still have a lot to research about this hormone, but the importance of its role in the human body seems clear.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is a hormone produced in the pituitary gland. This is the main endocrine gland in vertebrates. The hormones it secretes control the functioning of almost all other endocrine glands in the body (1).

Thus, ACTH is a corticotropic cell. These mainly produce adrenocorticotropic hormones that they place in the center. We’ll detail the characteristics of this particular hormone below.

Synthesis of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

This hormone is synthesized from a protein called proopiomelanocortin (POMC). This precursor protein is composed of 266 amino acids, and ACTH is composed of 39 amino acids. In addition, PMOC also generates other peptides, such as:

- Lipotropin

- Endorphin

- Met-encephaline

- Melanocyte stimulating hormone

- Mid-lobe protein similar to corticotropin (CLIP)

Adrenocorticotrophin secretion

As we mentioned above, the secretion of the adrenocorticotropic hormone is pulsatile. This means that it follows a characteristic circadian rhythm, reaching its maximum rhythm at 6:00 a.m., and its minimum at midnight.

Thanks to the secretion of ACTH, suprarenal glucocorticoids are secreted, following a parallel daytime pattern. The biological half-life of ACTH in the circulation is less than ten minutes.

Modulators of ACTH synthesis and/or secretion

Stimulators

- CRH (main modulator)

- TNF (tumor necrosis factor)

- IL-1 (interleukin-1)

- CKK (cholecystokinin)

- VIP (vasoactive intestinal peptide)

- Alpha-adrenergic stimuli

- Acetylcholine

- Serotonin

Inhibitors

- Cortisol (main modulator)

- GABA

- Endorphins

- Encephalins

- Activin

- Galanin

- ANP (atrial natriuretic peptide)

- Substance P

Mechanism of action of adrenocorticotropic hormone

ACTH acts through a membrane receptor. This receptor is called the melanocortin receptor 2, a receptor coupled to G proteins. The second biological messenger is cAMP.

Action

ACTH acts in the following way:

- It preserves the homeostasis of metabolism and controls the endocrine reaction to stress.

- It induces steroidogenesis. This is a set of metabolic reactions that mainly ensure the synthesis of steroid hormones in a certain organ or tissue (corticoids, androgens, and, to a lesser extent, mineralocorticoids).

- It stimulates skin pigmentation, which is determined by the amount of melanin in the skin. This is because its molecule contains the sequence of melanocyte-stimulating hormones (MSH).

- It also produces a certain degree of lipolysis: the breakdown of food lipids into fatty acids during digestion.

Frequently, the inhibition of ACTH and the adrenal axis occurs due to the use of steroids. For example, in asthma, collagenopathies, and hematological diseases (1).

ACTH-related diseases

Cushing’s syndrome

This syndrome includes a series of clinical and biochemical abnormalities resulting from chronic exposure to excess cortisol produced by the adrenal cortex. Between 80 and 85% of this syndrome is caused by a pituitary adenoma that produces ACTH (3).

The differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome constitutes one of the greatest challenges in endocrinology. While the clinical manifestations are obvious in many cases, they can be very subtle in others. Weight gain with central fat redistribution affecting the face, neck, trunk, and abdomen is one of the most common clinical findings (4).

Thus, other important clinical data are the presence of facial plethora, hirsutism, acne, menstrual disorders, hypertension, proximal muscle weakness, stretch marks, carbohydrate intolerance, or diabetes (5).

Addison’s disease (6)

Addison’s disease is a syndrome characterized by a lack of glucose and/or mineralocorticoids. In this case, a deficient production of ACTH may occur, thus leading to a decrease in the production of glucocorticoids (secondary hypoadrenocorticism).

Secondary hypoadrenocorticism can be natural or iatrogenic. The natural form is due to the absence of normal adrenal stimulation by CRH or ACTH and denotes primary pituitary or hypothalamic failure. Thus, most of these cases are the result of inflammation, tumors, trauma, or hypothalamic or pituitary birth defects.

The iatrogenic form is the most common form of secondary hypoadrenocorticism in veterinary medicine. It occurs due to the exogenous administration of glucocorticoids, which suppress the normal production of pituitary ACTH. As a result, it promotes bilateral adrenal atrophy.

Addison’s disease is a slow and progressive process. It’s caused by the insufficient supply of adrenocortical hormones for the body’s normal requirements. Thus, they have their origin in the bilateral destruction of the adrenal cortex. In addition, the symptomatology doesn’t begin to appear until the loss of 90 percent or more of the adrenal tissue (7).

Thus, ACTH is a key hormone in the correct functioning of the nervous system. In fact, its malfunctioning involves some illnesses such as those we’ve seen, in addition to other hormonal disorders. Scientists still have a lot to research about this hormone, but the importance of its role in the human body seems clear.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

-

Brandan, N. C., Llanos, I. C., Miño, C. A., Ragazzoli, M. A., & Ruiz Díaz, D. A. (2007). Hormonas hipotalámicas e hipofisarias. Universidad Nacional de Nordeste. Facultad de Medicina.

- ¿Qué es esteroidogénesis?. Retrieved from https://www.cun.es/diccionario-medico/terminos/esteroidogenesis

-

Arias, E. A. S., & Castillo, V. A. (2016). Síndrome de Cushing adrenal dependiente de hormona luteinizante. Revista argentina de endocrinología y metabolismo, 53(1), 36-41.

-

Findling, J. W., & Raff, H. (2005). Screening and diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics, 34(2), 385-402.

-

Aron, D. C., Tyrrell, J. B., & Wilson, C. B. (1995). Pituitary tumors. Current concepts in diagnosis and management. Western journal of medicine, 162(4), 340.

-

Picazo, R. (2003). Hipoadrenocorticismo: enfermedad de Addison. Clínica veterinaria de pequeños animales, 23(3), 0155-162.

-

Candel González, F. J., Matesanz David, M., & Candel Monserrate, I. (2001, September). Insuficiencia corticosuprarrenal primaria: Enfermedad de Addison. In Anales de Medicina Interna (Vol. 18, No. 9, pp. 48-54). Arán Ediciones, SL.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.