Victor Leborgne - A Case in Neuroscience

The brain of Victor Leborgne is probably the most studied in the history of neuroscience. It’s still preserved in the Musee Dupuytren in Paris and scientists have examined it thousands of times. However, until a few years ago, there was very little information about this man, to whose brain we owe important scientific findings.

Victor Leborgne’s brain was in the museum for over a century. Thanks to him, scientists managed to identify the area that controls language. Nobody knows much about how it got there, not even if he authorized its donation to science. In any case, we owe him a lot. His condition illuminated a path for medical researchers to follow.

“Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition.”

-Adam Smith-

Cezary W. Domanski, psychologist and historian at the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Poland decided to investigate the story of Victor Leborgne. Until he began to investigate, people only knew Victor’s last name.

The beliefs of the era

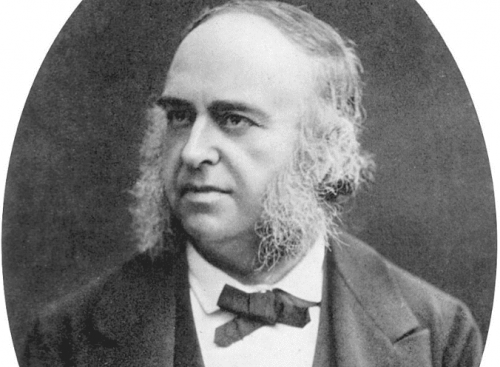

Dr. Paul Broca presented the case of Victor Leborgne in 1861 at the Society of Anthropology of Paris. It was quite a neurological finding. This doctor identified the exact region of the brain where language happened. Since then, we know it as Broca’s area.

Broca was not the first person to point out that language most likely originated in the frontal lobe. However, at that time, most people believe that mental functions originated in the hollow cavities of the brain. They believed that the cerebral cortex didn’t go beyond a mere shell made of blood vessels and tissues, with hardly any function.

The brain that helped him prove this theory belonged to a man whom Broca simply called Mr. Leborgne. It isn’t clear why he did this since there were no reservations regarding patient data at the time. We only know that he was a man who lost his ability to speak.

Victor Leborgne’s story

A Polish historian named Domanski began his research in Paris. He somehow obtained the death certificate from a man named Victor Leborgne, which coincided with the dates on which Dr. Broca made his famous presentation. From that point, he began to reconstruct the details of the story.

Victor Leborgne was born on July 21, 1820, in Moret-sur-Loing, a region of France. His father was a school teacher named Pierre Leborgne and his mother, Margueritte Savard, was a humble housewife. The couple procreated six children and Victor was their fourth.

From an early age, Leborgne suffered from seizures. Despite this, Victor led a relatively normal life. He trained as a “formier” (an artisan who makes wooden lasts for shoe manufacturers). Tanneries abounded in the town where he was born and shoemaking was a very common trade.

Loss of speech and discovery

Everything indicates that Leborgne began suffering from seizures and these became increasingly continuous and severe. At the age of 30, he had a very strong one that left him speechless. He arrived at Hospice de Bicêtre two months after losing his speech and remained there for the next 21 years of his life, until the day he died.

In principle, Victor Leborgne didn’t present any other problems besides his inability to speak. Apparently, he understood everything he heard. However, when he wanted to speak, he could only say “tan”. Some people believe it had something to do with his profession.

After about 10 years, Leborgne began to show signs of deterioration. For instance, his arm and right leg weakened and he began to lose his sight and cognitive faculties. His depression led him to stay in bed for several years and he also suffered from gangrene. Then, he found Dr. Broca.

When Victor Leborgne died, Broca did his autopsy and found there was an anomaly in his frontal lobe. Thus, this allowed him to test his hypothesis that changed neuroscience forever. Humankind owes a lot to this man science forgot until now.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Giménez-Roldán, S. (2017). Una revisión crítica sobre la contribución de Broca a la afasia: desde la prioridad al sombrerero Leborgne.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.