Uncovering V, The Revolutionary Leader in V for Vendetta

V is the emblematic hero of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s comic V for Vendetta. Of course, most people probably know this story better through the eponymous 2005 film. The comic began to be published during the 80s. They published it in Warrior, a British magazine. After that, they published it under the famous United States brand, DC Comics.

This change in distribution and its later film adaptation brought the work into mainstream consciousness. This is despite the fact that at the beginning they considered it to be a niche work. Many said it was an outsider and “not for everyone”. After one of Hollywood’s titans, Warner Bros., got ahold of it, they softened it, adapted it, and made it more “digestible”. This angered Alan Moore so much that he asked them to remove his name from the credits.

V for Vendetta‘s creators developed it at a time when the United Kingdom was under Margaret Thatcher’s government. Her political ideas and policies contrast sharply with Alan Moore’s anarchist philosophy as well as David Lloyd’s non-conformist one. Both authors were strongly influenced by their own contemporary society. The social problems of their country strongly influenced them. How would the world turn out if totalitarian governments won out in the end?

The dystopian future of V for Vendetta

V for Vendetta presents a dystopian future in which dominant and conservative fascism has come to power. After a war, fear swept British society. That lead citizens to support their leader, Susan. In exchange for protection and stability, they surrendered all their culture and liberty to this leader.

All works of art, such as books, have disappeared here. The government eliminated all memory of history, as well as those who died in the resettlement camps. People who have no history also have no references. As such, a government can more easily manipulate them.

This may remind you of works such as Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 or George Orwell’s 1984. These novels present futures without freedom or history. They’re societies where the population seems to be half-asleep despite having lost their most fundamental rights. Amid all of this oppression, V rises as the hero/villain that drives the United Kingdom to an awakening.

And there are more than just passing similarities to your society. The mass media tries to control and manipulate people. There’s also a culture of conformism, fear of change, the accumulation of privileges and wealth by the few, etc. Why fight for your rights if you can buy a car instead? That’s the society that we see in V for Vendetta. This is a society that doesn’t remember its past. It’s lost all of its ideals and isn’t even familiar with equality.

V is a character who’s past you know nothing about. You don’t know who he was before he came to the Larkhill resettlement camp. You do, however, get to know that he survived all the experiments they conducted on him. As opposed to the rest of the population, he also remembers his ideals, history, and art. And he’s arrived to save his society. He wants to make the people recover their sense, put their fears aside, and fight for justice.

“People shouldn’t be afraid of their government. Governments should be afraid of their people.”

–V for Vendetta–

V behind the mask

It’s impossible to “unmask” V without resorting to plot spoilers. That goes for the comic as well as for the film. We’re going to be focusing on the former for this article because it’s the original work. Moore tends to “demystify” both his heroes and villains. The same happens to the Joker in The Killing Joke. V is seen as a terrorist or villain. At the beginning of the work, he himself states that he’s “the black sheep”. But is V truly a villain?

He’s for the government, that’s for sure. V is also a villain for false security and for everyone who sees the foundations of their power tremble. That’s what happens to the bishop as well as to Susan, the leader herself. The media, which is completely under the control of power, tries to spread fear among the population. That same fear allows the fascists to conquer the United Kingdom. The government brands V a terrorist. In a certain way, you can see him as such, keeping in mind that he uses violence to achieve his ends. What Moore’s trying to show here is that perhaps those who had always been the good guys perhaps aren’t so good after all.

The fact of the matter is that peaceful revolutions rarely triumph over oppressive regimes. This goes especially for such cases where the political or social revolutions broke markedly from the order before them. This occurred, for example, in the French Revolution. V wants peace and equality, but to get those, he needs to use violence. Laws and justice are at the service of the powerful. So V has no option but to disobey and take justice into his own hands.

A.S. Cohan has a study on political theory called Introduction to Revolutionary Ideas. In this work, he deals with a series of matters that affect the revolution. He also shows us how, in most cases, a revolution isn’t necessarily linked to violence.

Despite this, other scholars such as Hannah Arendt suggest revolution could be a problem when trying to establish a model that would permit revolutionary ideas to triumph. V for Vendetta shows us the steps toward revolution. However, it doesn’t show us its completion. The ideal is so perfect that Moore and Lloyd never present it in their comic.

“Behind this mask there’s more than just flesh. Beneath this mask there’s an idea… and ideas are bulletproof.”

–V from Vendetta–

V, the legacy

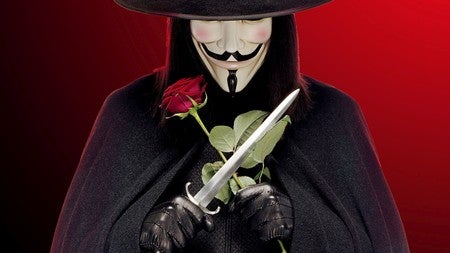

Who’s hiding behind that mask? Or better yet, who does it belong to? V’s famous mask is the visage of Guy Fawkes. He was a historical personage who tried to blow up the British Parliament in 1605. Fawkes was a Catholic. In light of Protestant oppression, he decided, without success, to take justice into his own hands. Moore and Lloyd reclaimed this character, along with his non-conformist views and his desire to snatch up equality. He’s the face of V.

The Guy Fawkes mask has become a contemporary legend in its own right. This is a legend that mass society itself has created. Roland Barthes explained this in detail in his work Mythologies. Today, we see this image at protests and on social media. It’s become something of a tool to express non-conformity. That mask invites you to conquer your fears. It exhorts you to fight for what you believe is just.

Evey is the opposite. She’s like us. She’s afraid, but V will give her up. That way she becomes free. Fear is one of the key themes in the work. The government, for example, uses fear to manipulate their people. In order to maintain his legacy alive and ensure that the revolution is from and for everyone, V ensures that Evey overcomes the barrier of fear. Through his death, she frees all of us.

The name itself, “Evey” has certain Biblical connotations. It reminds you of Eve who was the first woman and mother of all people. She puts on the mask when V dies. She’ll subsequently become the new leader, the new V.

Mass media helps you avoid reality. Nevertheless, its impact is so great that, if someone were to use it well, they could deliver a different message. V takes control of television broadcasts to send out a message to the population. That’s how he takes control of what was once a symbol of power and oppression. He makes it his own and strengthens his message. The film version is a candy-coated version of the comic. However, its spread is so broad that it’s had an impact on mainstream society. It’s created a mythos, a symbol that can wake people up.

V for Vendetta invites you to step outside of your comfort zone. It encourages you not to allow yourself to be manipulated. The film asks you to overcome barriers and achieve a fairer and more egalitarian world.

“Our masters haven’t heard the people’s voice for generations and it’s much, much louder than they care to remember.”

-Alan Moore, V for Vendetta–

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Arent, H. (2006): Sobre la revolución. trad. Pedro Bravo. Madrid, Alianza.

- Barthes, R. (1980): Mitologías. trad. H. Schmucler. Madrid, Siglo Veintiuno.

- Cohan, A.S. (1997): Introducción a las teorías de la revolución. trad. Víctor Peral Domínguez. Madrid, Espasa-Calpe.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.