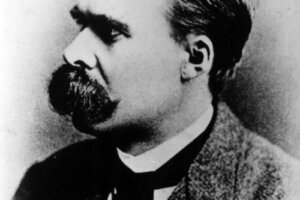

The Possible Origin of Nietzsche's Madness

Written and verified by the psychologist Gorka Jiménez Pajares

Over the years, many research articles have been published in an attempt to find the key to the disease suffered by Friedrich Nietzsche. The great philosopher and thinker of German origin died at the age of 56. He was suffering from symptoms for which medicine at the time was unable to offer an explanation. In fact, until recently, the cause of Nietzsche’s madness remained a mystery.

The diagnosis he received at the time was similar to that of many other artists suffering from syphilis. He experienced general paralysis. This was due to lues, a form of neurosyphilis. However, more recent research suggests that a more appropriate diagnosis for his illness would be frontotemporal dementia.

“The real world is much smaller than the imaginary.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche-

The symptoms of Nietzsche’s madness

Nietzsche suffered a progressive and devastating deterioration. It started at the age of 24 when he started teaching philology. Early in his illness, his symptoms included severe headaches and problems with his right field vision.

The symptoms of Nietzsche’s illness were so intense that he was forced to abandon his position as a professor and settle in Turin, Italy. Marcelo Miranda claims that it was here where Nietzsche’s mental disorder became unmanageable. Consequently, he needed to be hospitalized, first in Basel and later in Jena.

Among the symptoms of Nietzsche’s madness were the following:

- Hyperorality behaviors. This means the compulsive need to place both edible and inedible objects into the mouth. It’s accompanied by sucking, chewing, biting, etc.

- Strange and negligent behavior in respect of caring for one’s body.

- Hyperphagia or voracious appetite.

- Anger attacks.

- Aggressive behaviors.

- Coprophagy. Eating one’s own feces.

- Megalomanic or delusions of grandeur.

- Dramatic personality changes.

“Nietzsche signed his letters ‘Phoenix’, ‘Antichrist’ and ‘Dionysus’ and sent irreverent letters to the Kaiser and Bismarck. He called himself ‘the redeemer of all millennia’.”

-Marcelo Miranda-

Frontotemporal dementia

Certain research supports the fact that Nietzsche’s madness can currently be explained as frontotemporal dementia.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) claims that this dementia is characterized by having an insidious onset and a gradual (neither rapid nor slow) progression. Moreover, symptoms similar to those of Nietzsche occur:

- Changes in behavior. For example, disinhibition, apathy, inertia, lack of empathy, and the existence of obsessions and compulsions. The aforementioned hyperphagia and hyperorality would be included here. In addition, there are changes in social cognition. This means the way the sufferer processes information from the interpersonal context is intensely altered.

- Changes in language. These are related to its reception, processing, and expression.

For a diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia to be made, other possible causes must be ruled out. For example, a stroke, a tumor mass, or a thyroid disease, as well as certain other psychiatric diseases.

The etiology of frontotemporal dementia remains unknown. That said, today, there are some accepted facts that we mention below.

“I need companions, living ones, not dead companions and corpses which I carry with me wherever I wish.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche-

Causes of frontotemporal dementia

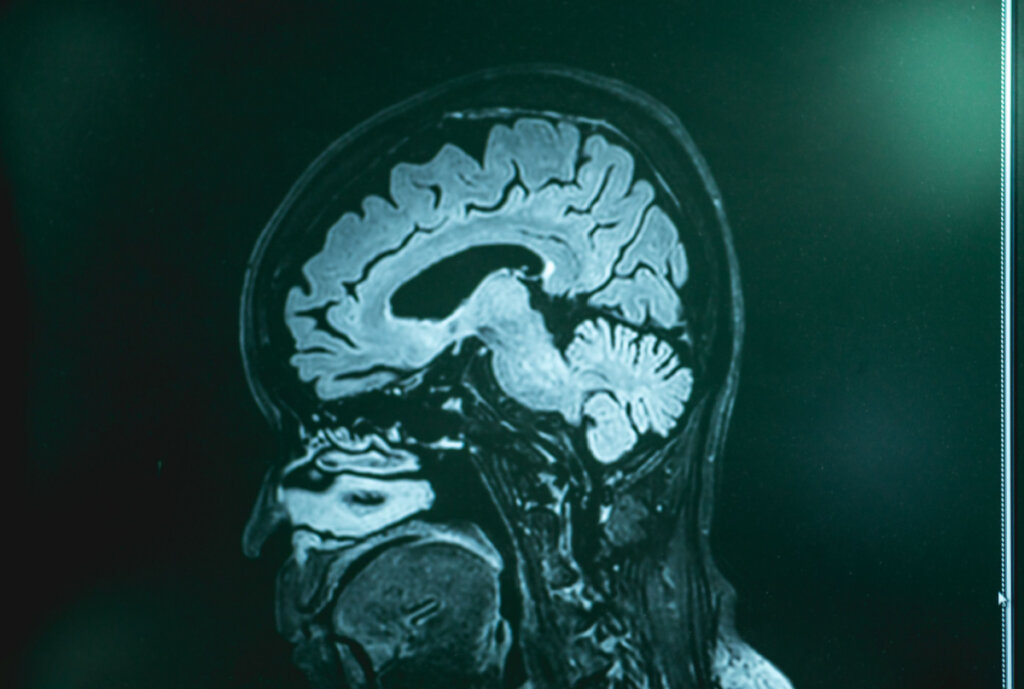

Despite the cause-effect ignorance regarding this particular type of dementia, various hypotheses are being considered, some with greater success. Through neuroimaging procedures, certain atrophy can be observed in these patients. In other words, shrinkage of certain areas of the cortex, especially in the temporal and frontal cortex.

“It is a very rare and heterogeneous type of dementia with generally unknown etiology (in 50 percent of cases it is not known).”

-Amparo Belloch-

The professor of psychopathology, Amparo Belloch, states that some genes that could be involved have been identified:

- The gene that encodes the tau protein. It’s located on chromosomes 3 and 17.

- The MAPT microtubule-related gene.

- The granulin-related gene GRN (progranulin gene).

- The C9ORF72 valosin-containing protein gene.

In frontotemporal dementia, symptoms usually start between the ages of 40 and 65 years. However, there may be cases, such as Nietzsche’s, in which they occur earlier. Once manifested, the disease usually causes the death of the person three to four years after diagnosis.

This type of dementia encompasses approximately 20 percent of all registered dementia cases. If there’s a history of this type of dementia in your family, you may well be interested in visiting a medical professional. They might be able to tell you if there are any risk factors on which you can intervene.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

-

Campohermoso Rodríguez, O. F. (2008). De la Genialidad a la Locura Friedrich Nietzsche. Cuadernos Hospital de Clínicas, 53(2), 91-96.

-

Miranda, M. (2016). LA DEMENCIA DE FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE O¿ CÓMO PUEDE MODIFICAR LA CREATIVIDAD UNA DEMENCIA?. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 27(3), 413-415.

-

Parálisis general. (s. f.). https://medlineplus.gov/spanish/ency/article/000748.htm

-

Miranda, M., & Navarrete, L. (2007). ¿ Qué causó la demencia de Friedrich Nietzsche?. Revista médica de Chile, 135(10), 1355-1357.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (Dsm-5-Tr(tm)) (5.a ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

-

Condor, S., & Antaki, C. (2000). Cognición social y discurso. El discurso como estructura y proceso. Barcelona: Gedisa, 453-489.

-

Martínez Valdés, H. (2021). Revisión sistemática: Diagnóstico diferencial entre Enfermedad de Alzheimer y LATE en pacientes con deterioro cognitivo.

- Belloch, A. (2022a). Manual de psicopatología, vol II.

-

Demencia frontotemporal – Síntomas y causas – Mayo Clinic. (2021, 16 noviembre). https://www.mayoclinic.org/es-es/diseases-conditions/frontotemporal-dementia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354737

-

Biologia, A. (2022, 20 julio). Analisis-del-gen-GRN-en-pacientes-con-demencia-frontotemporal-DFT-y-del-gen-C9ORF72-en-pacientes-con-DFT-y-esclerosis-lateral-amiotrofica-ELA. Passei Direto. https://www.passeidireto.com/arquivo/111101587/analisis-del-gen-grn-en-pacientes-con-demencia-frontotemporal-dft-y-del-gen-c-9-/4

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.