The Philosophy of Mental Illness

The philosophy of mental illness is an interdisciplinary field of study. It combines methods and points of view from philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and ethics to analyze mental illness.

Philosophers of mental illness look at the ontological, epistemological, and normative problems that arise from the range of understanding of mental illness. One of the central questions of this philosophy is if it’s possible for the concept of mental illness to have an appropriate and objective scientific definition.

Thus, one point of discussion is whether mental illnesses should be understood as a form of mental dysfunction. The philosophy of mental illness also analyzes whether mental illnesses are better identified as discrete mental entities, with clear criteria for inclusion/exclusion, or as points along a continuum between normal and unwell.

Philosophy of mental illness: a criticism of the diagnostic process

Philosophers who criticize the idea of mental illness argue that it isn’t possible to define the term “mental illness”. Also, they argue that the categories of mental illnesses impose pre-existing norms and power dynamics.

Also, there are many questions about the relationship between the role of values when it comes to understanding mental illness. Philosophers think about how those values relate to the concept of illness in general.

Philosophers who are part of the neurodiversity movement believe that society as a whole needs to revise the concept of mental illness. It’s important for it to reflect the different types of cognitions that people display without stigmatizing individuals who are statistically “abnormal”.

The diagnosis problem

In addition, there are epistemological problems that are related to the relationship between mental illness and diagnosis. Historically, the main issue has centered around how mental illness nosologies (classification frameworks), especially the DSM, relate mental dysfunctions with observable symptoms.

In the DSM framework, mental dysfunction can be identified through the presence or absence of a set of symptoms from a verification list. Those who disagree with the use of behavior-based symptoms to diagnose mental illness argue that the symptoms are useless without an appropriate theoretical framework of what it means to say that a mental mechanism is dysfunctional.

Consequently, a diagnostic system should be capable of distinguishing between a person with a genuine mental illness and someone who’s going through a difficult time in their lives. Critics argue that the DSM, as it stands today, isn’t capable of doing that.

Is the concept of mental illness even trustworthy?

Also, there are related questions about the nature and role of values in mental illness. The first question is if mental illness is a value-neutral concept. Nosologies of mental illnesses attempt to come up with value-neutral definitions of disorders.

In an ideal world, the concepts in manuals such as the DSM would reflect a universal underlying human reality. The mental disorders they define shouldn’t represent culturally relative value judgments of what happens in the mind.

Philosophical criticisms of the concept of mental illness

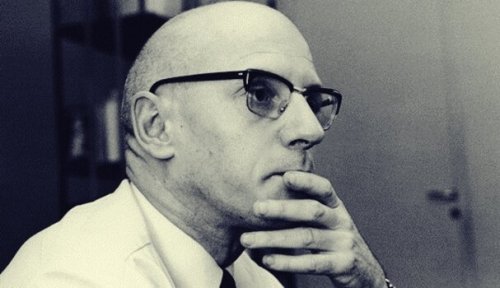

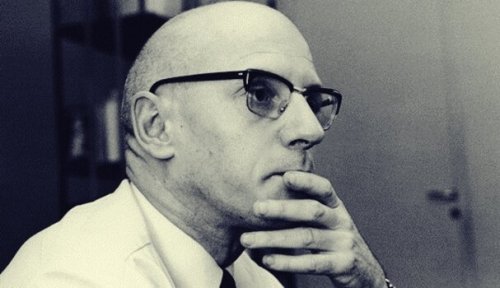

Michel Foucault was one of the first critics of the idea of mental illness and mental health institutions. Foucault argued that, historically, psychiatric asylums served as places to apply models of rationality that gave privilege to individuals who were already in positions of power.

This model excluded many members of society from the circle of people with rational agency. Asylums were places where society housed “undesirable” people. Thus, they reinforced pre-existing power dynamics.

Foucault believed that ideas about mental illness are social constructions that serve the same purpose as race, gender, social class, and sexual orientation. Therefore, certain individuals and institutions use the concept of mental illness to maintain and expand their power. The goal is to preserve social order, as defined by the people in power.

A constructivist perspective of mental illness

Constructivists can take a range of positions on the question of social constructions and mental illness. A less radical constructivist, for example, might argue that cultures impose models of “ideal agency”. Then, society uses them to label sets of human behavior.

From this perspective, behavioral syndromes can be present in all cultures. Thus, each culture develops a theory of ideal agency, which means that certain syndromes are labeled “illnesses”. At the same time, other cultures group the syndromes together in a different way, depending on their values.

The set of behaviors that we label “symptoms of depression” only exists because doctors have lumped them together, for many different reasons we won’t explain here. The only way, then, to explain why a particular set of behaviors, feelings, or thoughts are grouped together that way is because doctors and experts have created that grouping.

If you want to talk about the characteristic behaviors involved in a heart attack, it’s easy to look at the causal history that unifies that particular behavior. The symptoms of mental illnesses, however, lack an explanation for their being grouped together that’s independent of their clinical presentation.

From this point of view, the syndromes are similar to what Ian Hacking called “interactive types”. Natural types represent groupings that exist independent of outside opinions. However, with interactive types, individuals experience themselves according to an established point of view; they change their feelings and emotions to adjust to a particular type.

Examples of the interactive type with mental illness

You should think of multiple personality disorder (now known as dissociative identity disorder) as an interactive type. In other words, multiple personality disorder isn’t a basic issue with human neurology that neuroscientists can discover.

Once the concept of multiple personality disorder is identified, many people will be labeled as such. These ideas will lead to diagnoses without any underlying causes in the brain that can be detected.

This label effectively hides other possible explanations for the mental illness that are less essentialist and even pluralist within the philosophy.

In conclusion, the philosophy of mental illness is a perspective that, in many ways, teaches psychology how to understand a person outside of the medical field and iatrogenic labels.

The philosophy of mental illness is an interdisciplinary field of study. It combines methods and points of view from philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and ethics to analyze mental illness.

Philosophers of mental illness look at the ontological, epistemological, and normative problems that arise from the range of understanding of mental illness. One of the central questions of this philosophy is if it’s possible for the concept of mental illness to have an appropriate and objective scientific definition.

Thus, one point of discussion is whether mental illnesses should be understood as a form of mental dysfunction. The philosophy of mental illness also analyzes whether mental illnesses are better identified as discrete mental entities, with clear criteria for inclusion/exclusion, or as points along a continuum between normal and unwell.

Philosophy of mental illness: a criticism of the diagnostic process

Philosophers who criticize the idea of mental illness argue that it isn’t possible to define the term “mental illness”. Also, they argue that the categories of mental illnesses impose pre-existing norms and power dynamics.

Also, there are many questions about the relationship between the role of values when it comes to understanding mental illness. Philosophers think about how those values relate to the concept of illness in general.

Philosophers who are part of the neurodiversity movement believe that society as a whole needs to revise the concept of mental illness. It’s important for it to reflect the different types of cognitions that people display without stigmatizing individuals who are statistically “abnormal”.

The diagnosis problem

In addition, there are epistemological problems that are related to the relationship between mental illness and diagnosis. Historically, the main issue has centered around how mental illness nosologies (classification frameworks), especially the DSM, relate mental dysfunctions with observable symptoms.

In the DSM framework, mental dysfunction can be identified through the presence or absence of a set of symptoms from a verification list. Those who disagree with the use of behavior-based symptoms to diagnose mental illness argue that the symptoms are useless without an appropriate theoretical framework of what it means to say that a mental mechanism is dysfunctional.

Consequently, a diagnostic system should be capable of distinguishing between a person with a genuine mental illness and someone who’s going through a difficult time in their lives. Critics argue that the DSM, as it stands today, isn’t capable of doing that.

Is the concept of mental illness even trustworthy?

Also, there are related questions about the nature and role of values in mental illness. The first question is if mental illness is a value-neutral concept. Nosologies of mental illnesses attempt to come up with value-neutral definitions of disorders.

In an ideal world, the concepts in manuals such as the DSM would reflect a universal underlying human reality. The mental disorders they define shouldn’t represent culturally relative value judgments of what happens in the mind.

Philosophical criticisms of the concept of mental illness

Michel Foucault was one of the first critics of the idea of mental illness and mental health institutions. Foucault argued that, historically, psychiatric asylums served as places to apply models of rationality that gave privilege to individuals who were already in positions of power.

This model excluded many members of society from the circle of people with rational agency. Asylums were places where society housed “undesirable” people. Thus, they reinforced pre-existing power dynamics.

Foucault believed that ideas about mental illness are social constructions that serve the same purpose as race, gender, social class, and sexual orientation. Therefore, certain individuals and institutions use the concept of mental illness to maintain and expand their power. The goal is to preserve social order, as defined by the people in power.

A constructivist perspective of mental illness

Constructivists can take a range of positions on the question of social constructions and mental illness. A less radical constructivist, for example, might argue that cultures impose models of “ideal agency”. Then, society uses them to label sets of human behavior.

From this perspective, behavioral syndromes can be present in all cultures. Thus, each culture develops a theory of ideal agency, which means that certain syndromes are labeled “illnesses”. At the same time, other cultures group the syndromes together in a different way, depending on their values.

The set of behaviors that we label “symptoms of depression” only exists because doctors have lumped them together, for many different reasons we won’t explain here. The only way, then, to explain why a particular set of behaviors, feelings, or thoughts are grouped together that way is because doctors and experts have created that grouping.

If you want to talk about the characteristic behaviors involved in a heart attack, it’s easy to look at the causal history that unifies that particular behavior. The symptoms of mental illnesses, however, lack an explanation for their being grouped together that’s independent of their clinical presentation.

From this point of view, the syndromes are similar to what Ian Hacking called “interactive types”. Natural types represent groupings that exist independent of outside opinions. However, with interactive types, individuals experience themselves according to an established point of view; they change their feelings and emotions to adjust to a particular type.

Examples of the interactive type with mental illness

You should think of multiple personality disorder (now known as dissociative identity disorder) as an interactive type. In other words, multiple personality disorder isn’t a basic issue with human neurology that neuroscientists can discover.

Once the concept of multiple personality disorder is identified, many people will be labeled as such. These ideas will lead to diagnoses without any underlying causes in the brain that can be detected.

This label effectively hides other possible explanations for the mental illness that are less essentialist and even pluralist within the philosophy.

In conclusion, the philosophy of mental illness is a perspective that, in many ways, teaches psychology how to understand a person outside of the medical field and iatrogenic labels.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.