Gut Microbiota - Definition, Relevance, and Medical Uses

Written and verified by The nurse Daniel Baldó Vela

Did you know that gut microbiota refers to the microbiota in the intestinal tract? Scientists define microbiota as “the assemblage of microorganisms in a defined environment,” such as bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses. The microbiota varies according to its surrounding environment. The term microbiota, also known as microbes, proceeds by the name of the environment in which it locates.

The human body hosts approximately 100 trillion microbiota, though some of these are useful, and some are harmful. Some scientists estimate that there are ten times more microbial cells in the body than there are human cells. Recent scientific advances in genetics have allowed humans to know a lot more about the microbes in the body.

Many countries invested a lot in researching the interactions within the human body’s ecosystem. Furthermore, they also invested in its relevance to health and disease. The two terms, microbiota and microbiome, are often used to mean the same thing, although they’re also used interchangeably. This article will perfectly explain the differences between them. You’ll also learn all about different uses and research in modern medicine.

Fast facts on gut microbiota

- Trillions of cells make up the human microbiota. For example, bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- The biggest populations of microbes reside in the gut. Other popular habitats include the skin and genitals.

- The microbial cells and their genetic material, the microbiome, live with humans from birth. This relationship is vital to health.

- Millions of microorganisms living inside the gastrointestinal tract amount to around four pounds of biomass. Nonetheless, every individual has a unique mix of species.

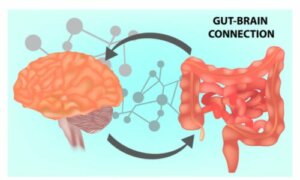

- The microbiota is important for nutrition and immunity and has effects on the brain and behavior. It implicates a number of diseases that cause a disturbance in the normal balance of microbes.

What exactly is the human microbiome?

The gut microbiota is with humans from birth, and it affects function throughout the body. The human microbiota consists of a wide variety of things, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other single-celled organisms that live in the body. Thus, the microbiome is the name given to all of the genes inside these microbial cells.

Every human being harbors anywhere between 10 trillion and 100 trillion microbial cells in a symbiotic relationship. This benefits both the microbes and their hosts, as long as your body is in a healthy state. Estimates vary. However, over 1,000 different species of microorganisms could make up the human microbiota. There are plenty of projects trying to decode the human genome by sequencing all human genes.

Similarly, the microbiome was subjected to intensive efforts to unravel all its genetic information. An intriguing online video about the human ecosystem helps understand it. The Genetic Science Learning Center of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, produced the video. It’ll surely help create a picture of this delicate, yet vital, relationship.

Different types of microbes

There’s a range of habitats for every type of microbes in your body, and each is different. Your forearm’s dry environment completely differs from your armpit’s wet and oily environment. The microbes in the body are small; small enough that they make up only about two to three percent of the weight of the human body, despite outnumbering the cells.

A genius 2012 study published in Nature by the Human Microbiome Project Consortium found many important things, including:

- Samples of mouth and stool microbial communities are particularly diverse.

- In contrast, samples from vaginal sites show particularly simple microbial communities.

The study showed the great diversity of the human microbiome across a group of healthy Western people, though posed questions for further research. How do microbial populations within each of us vary across a lifetime? Are patterns of colonization by beneficial microbes the same as those shown by disease-causing microbes?

What’s the gut microbiota?

Many years ago, experts called the gut microbiota the microflora of the gut. Around this time, in 1996, Dr. Rodney Berg wrote about the gut microbiota. Rodney is a brilliant scholar of Louisiana State University’s Microbiology and Immunology department. He wrote about its “profound” importance in a research paper he published in the journal Trends in Microbiology. “The indigenous gastrointestinal tract microflora has profound effects on the anatomical, physiological, and immunological development of the host”, Dr. Berg wrote.

The research paper adds, “The indigenous microflora stimulates the host immune system to respond more quickly to pathogen challenge and, through bacterial antagonism, inhibits colonization of the GI tract by overt exogenous pathogens”. Fortunately, this symbiotic relationship benefits both humans, and the presence of this normal flora includes microorganisms, such as those present in the environment. You can find these in practically all animals from the same habitat, though these native microbes include harmful bacteria. It can also overcome the body’s defenses that separate them from vital systems and organs.

There are beneficial bacteria in the gut, though there are also harmful bacteria that can cross into wider systems, causing local infections of the GI tract. These infections include many things. For instance, food poisoning and other GI diseases that result in diarrhea and vomiting.

The mighty gut microbiota contains over three million genes, which makes it 150 times more genetically varied than the human body. The gut microbiota of each individual is unique. It can heavily contribute to how people fight disease and digest food and even their mood and psychological processes.

Importance of the human microbiota

Firstly, there was a range of links found between gut microbes and heart disease. Microorganisms evolved alongside humans. They now form an integral part of life, carrying out a range of vital functions. They implicate both health and disease. According to recent research, there are links between bacterial populations, whether normal or disturbed, and the following diseases:

- Asthma.

- Autism.

- Cancer.

- Celiac disease.

- Colitis.

- Diabetes.

- Eczema.

- Heart disease.

- Malnutrition.

- Multiple sclerosis.

- Obesity.

Similarly, the human microbiome utterly influences many other things. The following four areas are very important to health:

- Nutrition.

- Immunity.

- Behavior.

- Disease.

Nutrition

Not only does the gut microbe absorb energy from food, but it’s also highly essential. As a matter of fact, it helps humans effectively take in nutrients. Gut bacteria also help you perfectly break down complex molecules, such as in meats and vegetables. Without the aid of gut bacteria, you can’t digest plant cellulose, and gut microbes use their metabolic activities to influence food cravings.

They also dramatically influence feelings of being full. The diversity of the microbiota utterly relates to the diversity of the diet. Younger adults trying out a wide variety of foods display a highly varied gut microbiota. On the other hand, adults who follow a distinct dietary pattern don’t have a varied microbiota.

Immunity

From the moment an animal is born, they start building their microbiome, though humans acquire their first microbes when they enter their mother’s cervix. This happens just as they arrive in this beautiful world. Therefore, without these early microbial guests, you wouldn’t have adaptive immunity. Immunity is a vital defensive mechanism. It effectively learns how to respond to microbes after encountering them.

It allows for a quicker and more effective response to disease-causing organisms. Rodents that don’t show any microorganisms whatsoever show a range of pathological effects. An immune system that didn’t develop is among these animals. The microbiota also relates to autoimmune conditions and allergies, though it can be more likely to develop when exposure to microbes is disturbed early on.

Disease

Bacterial populations in the gastrointestinal system provided deep insights into gut conditions, including inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Low microbial diversity in the gut links to IBD as well as obesity and type 2 diabetes. The status of the gut microbiota also links to metabolic syndrome, though hanging the diet dramatically reduces these risk factors.

It’s imperative to make sure your diet includes prebiotics, probiotics, and other supplements. Gut microbes and their genetics affect many factors, such as energy balance, brain development, and cognitive function. There’s ongoing research on exactly how this occurs, and their research wants to discover how you can use this relationship for human benefit. Disturbing the microbiota with antibiotics can lead to disease, such as infections that become resistant to an antibiotic.

The microbiota also plays an important role in resisting intestinal overgrowth, though of externally introduced populations that would otherwise cause disease. The “good” bacteria compete with the “bad”, with some even releasing anti-inflammatory compounds.

New vital findings on the microbiome

There’s ongoing research into the impact of gut microbiota on overall health. They made a huge investment into research about microbial populations in the body and their genetics, while exploring links with health and disease. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched the Human Microbiome Project in 2007. This innovative research project aims to define the microbial species that affect humans.

The research also seeks to discover their relationships to health by producing large, publicly available datasets from genetic studies. You find most of the microorganisms living in humans in the gastrointestinal system. In fact, this is also where they made many new discoveries. Recent developments include further confirmation of ways to insert a new strain into existing microbiota.

Researchers used seaweed to control the gut microbiota of several mice in this study. There was also recent research about potential pathogens. It studied how pathogens from outside the body go about invading, and how they relate to the gut microbiota. This will help identify ways to limit the invasion of potentially harmful microbes and their disease-causing effects. As you can see, gut microbiota is becoming a cornerstone of preventive medicine.

Did you know that gut microbiota refers to the microbiota in the intestinal tract? Scientists define microbiota as “the assemblage of microorganisms in a defined environment,” such as bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses. The microbiota varies according to its surrounding environment. The term microbiota, also known as microbes, proceeds by the name of the environment in which it locates.

The human body hosts approximately 100 trillion microbiota, though some of these are useful, and some are harmful. Some scientists estimate that there are ten times more microbial cells in the body than there are human cells. Recent scientific advances in genetics have allowed humans to know a lot more about the microbes in the body.

Many countries invested a lot in researching the interactions within the human body’s ecosystem. Furthermore, they also invested in its relevance to health and disease. The two terms, microbiota and microbiome, are often used to mean the same thing, although they’re also used interchangeably. This article will perfectly explain the differences between them. You’ll also learn all about different uses and research in modern medicine.

Fast facts on gut microbiota

- Trillions of cells make up the human microbiota. For example, bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- The biggest populations of microbes reside in the gut. Other popular habitats include the skin and genitals.

- The microbial cells and their genetic material, the microbiome, live with humans from birth. This relationship is vital to health.

- Millions of microorganisms living inside the gastrointestinal tract amount to around four pounds of biomass. Nonetheless, every individual has a unique mix of species.

- The microbiota is important for nutrition and immunity and has effects on the brain and behavior. It implicates a number of diseases that cause a disturbance in the normal balance of microbes.

What exactly is the human microbiome?

The gut microbiota is with humans from birth, and it affects function throughout the body. The human microbiota consists of a wide variety of things, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other single-celled organisms that live in the body. Thus, the microbiome is the name given to all of the genes inside these microbial cells.

Every human being harbors anywhere between 10 trillion and 100 trillion microbial cells in a symbiotic relationship. This benefits both the microbes and their hosts, as long as your body is in a healthy state. Estimates vary. However, over 1,000 different species of microorganisms could make up the human microbiota. There are plenty of projects trying to decode the human genome by sequencing all human genes.

Similarly, the microbiome was subjected to intensive efforts to unravel all its genetic information. An intriguing online video about the human ecosystem helps understand it. The Genetic Science Learning Center of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, produced the video. It’ll surely help create a picture of this delicate, yet vital, relationship.

Different types of microbes

There’s a range of habitats for every type of microbes in your body, and each is different. Your forearm’s dry environment completely differs from your armpit’s wet and oily environment. The microbes in the body are small; small enough that they make up only about two to three percent of the weight of the human body, despite outnumbering the cells.

A genius 2012 study published in Nature by the Human Microbiome Project Consortium found many important things, including:

- Samples of mouth and stool microbial communities are particularly diverse.

- In contrast, samples from vaginal sites show particularly simple microbial communities.

The study showed the great diversity of the human microbiome across a group of healthy Western people, though posed questions for further research. How do microbial populations within each of us vary across a lifetime? Are patterns of colonization by beneficial microbes the same as those shown by disease-causing microbes?

What’s the gut microbiota?

Many years ago, experts called the gut microbiota the microflora of the gut. Around this time, in 1996, Dr. Rodney Berg wrote about the gut microbiota. Rodney is a brilliant scholar of Louisiana State University’s Microbiology and Immunology department. He wrote about its “profound” importance in a research paper he published in the journal Trends in Microbiology. “The indigenous gastrointestinal tract microflora has profound effects on the anatomical, physiological, and immunological development of the host”, Dr. Berg wrote.

The research paper adds, “The indigenous microflora stimulates the host immune system to respond more quickly to pathogen challenge and, through bacterial antagonism, inhibits colonization of the GI tract by overt exogenous pathogens”. Fortunately, this symbiotic relationship benefits both humans, and the presence of this normal flora includes microorganisms, such as those present in the environment. You can find these in practically all animals from the same habitat, though these native microbes include harmful bacteria. It can also overcome the body’s defenses that separate them from vital systems and organs.

There are beneficial bacteria in the gut, though there are also harmful bacteria that can cross into wider systems, causing local infections of the GI tract. These infections include many things. For instance, food poisoning and other GI diseases that result in diarrhea and vomiting.

The mighty gut microbiota contains over three million genes, which makes it 150 times more genetically varied than the human body. The gut microbiota of each individual is unique. It can heavily contribute to how people fight disease and digest food and even their mood and psychological processes.

Importance of the human microbiota

Firstly, there was a range of links found between gut microbes and heart disease. Microorganisms evolved alongside humans. They now form an integral part of life, carrying out a range of vital functions. They implicate both health and disease. According to recent research, there are links between bacterial populations, whether normal or disturbed, and the following diseases:

- Asthma.

- Autism.

- Cancer.

- Celiac disease.

- Colitis.

- Diabetes.

- Eczema.

- Heart disease.

- Malnutrition.

- Multiple sclerosis.

- Obesity.

Similarly, the human microbiome utterly influences many other things. The following four areas are very important to health:

- Nutrition.

- Immunity.

- Behavior.

- Disease.

Nutrition

Not only does the gut microbe absorb energy from food, but it’s also highly essential. As a matter of fact, it helps humans effectively take in nutrients. Gut bacteria also help you perfectly break down complex molecules, such as in meats and vegetables. Without the aid of gut bacteria, you can’t digest plant cellulose, and gut microbes use their metabolic activities to influence food cravings.

They also dramatically influence feelings of being full. The diversity of the microbiota utterly relates to the diversity of the diet. Younger adults trying out a wide variety of foods display a highly varied gut microbiota. On the other hand, adults who follow a distinct dietary pattern don’t have a varied microbiota.

Immunity

From the moment an animal is born, they start building their microbiome, though humans acquire their first microbes when they enter their mother’s cervix. This happens just as they arrive in this beautiful world. Therefore, without these early microbial guests, you wouldn’t have adaptive immunity. Immunity is a vital defensive mechanism. It effectively learns how to respond to microbes after encountering them.

It allows for a quicker and more effective response to disease-causing organisms. Rodents that don’t show any microorganisms whatsoever show a range of pathological effects. An immune system that didn’t develop is among these animals. The microbiota also relates to autoimmune conditions and allergies, though it can be more likely to develop when exposure to microbes is disturbed early on.

Disease

Bacterial populations in the gastrointestinal system provided deep insights into gut conditions, including inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Low microbial diversity in the gut links to IBD as well as obesity and type 2 diabetes. The status of the gut microbiota also links to metabolic syndrome, though hanging the diet dramatically reduces these risk factors.

It’s imperative to make sure your diet includes prebiotics, probiotics, and other supplements. Gut microbes and their genetics affect many factors, such as energy balance, brain development, and cognitive function. There’s ongoing research on exactly how this occurs, and their research wants to discover how you can use this relationship for human benefit. Disturbing the microbiota with antibiotics can lead to disease, such as infections that become resistant to an antibiotic.

The microbiota also plays an important role in resisting intestinal overgrowth, though of externally introduced populations that would otherwise cause disease. The “good” bacteria compete with the “bad”, with some even releasing anti-inflammatory compounds.

New vital findings on the microbiome

There’s ongoing research into the impact of gut microbiota on overall health. They made a huge investment into research about microbial populations in the body and their genetics, while exploring links with health and disease. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched the Human Microbiome Project in 2007. This innovative research project aims to define the microbial species that affect humans.

The research also seeks to discover their relationships to health by producing large, publicly available datasets from genetic studies. You find most of the microorganisms living in humans in the gastrointestinal system. In fact, this is also where they made many new discoveries. Recent developments include further confirmation of ways to insert a new strain into existing microbiota.

Researchers used seaweed to control the gut microbiota of several mice in this study. There was also recent research about potential pathogens. It studied how pathogens from outside the body go about invading, and how they relate to the gut microbiota. This will help identify ways to limit the invasion of potentially harmful microbes and their disease-causing effects. As you can see, gut microbiota is becoming a cornerstone of preventive medicine.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Andreo Martínez, P., García Martínez, P. & Sánchez Samper, E.P. (2017). The gut microbiome and its relation to mental illnesses through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Discapacidad Clínica Neurociencias, 4(2): 52-58. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6123886

- Arumugam, M. et al (2011). Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature, 12(473): 174-180. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature09944

- Blanco, J.R., Gómez Eguílaz, M., Pérez Martínez, L. & Ramón Trapero, J.L. (2019). El eje microbiota-intestino-cerebro y sus grandes proyecciones. Neurología, 68: 111-117. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://www.neurologia.com/articulo/2018223

- Claes, S., Darzi, Y., Falony, G., Joossens, M., Kurilshikov, A., Raes, J., Schiwech, C., Tigchelaar, E.F., Tito, R.Y., Van Oudenhove, L., Valles Colomer, M., Vieira Silva, S., Wang, J., Wicjmenga, C. & Zhernakova, A. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology, 4(4): 623-632. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30718848/

- Gómez Chavarín, M. & Morales Gómez, M.R. (2017). Comunicación bidireccional de la microbiota intestinal en el desarrollo del sistema nervioso central y en la enfermedad de Parkinson. Arch Neurocien., 22(2): 53-71. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/arcneu/ane-2017/ane172f.pdf

- Yatsunenko, T. et al (2012). Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature, 486: 222-227. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11053

- Torrijo Bueno, B. (2017). Influencia de la microbiota en pacientes con trastornos del comportamiento (tesis de máster). Universidad de Cantabria, Cantabria, España. Consultado el 05/07/2019. Recuperado de: https://repositorio.unican.es/xmlui/handle/10902/12432

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.