Gender and Corruption: Are They Related?

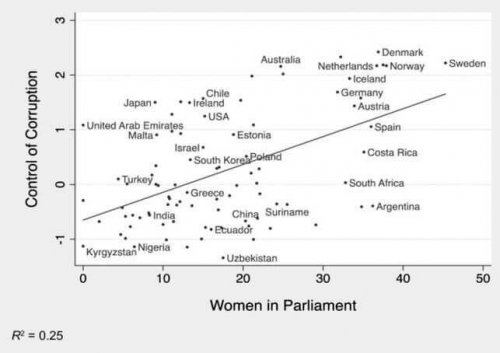

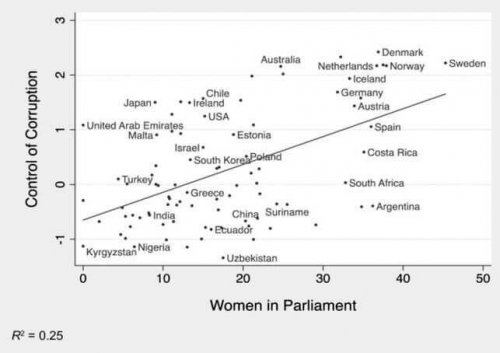

Is there less corruption when women participate in politics? Are gender and corruption related? In 2015, Stensöta, Wängnerud, and Svensson carried out a study with which they tried to answer these questions. This investigation touches on the relationship between a greater number of women in parliament and a greater capacity to control corruption.

Are women less corrupt than men? The simple answer is yes. However, the relationship between gender and corruption has many nuances. First of all, why are women less corrupt? Are they less selfish? Do they have more self-control? Or do they not have the same opportunities to be corrupt?

This last question seems to have been answered in the recent study published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. Authors Chandan Jha of Le Moyne College and Sudipta Sarangi of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University showed that the relationship between gender and corruption isn’t caused by gender differences in social status. Actually, these authors suggest that corruption rates are unlikely to increase when women attain high social statuses.

In addition, this study led to another important discovery. A thorough analysis of 17 European countries found that the presence of women in local governments was negatively related to bribes.

“No science is immune to the infection of politics and the corruption of power.”

-Jacob Bronowski-

The Relationship between Gender and Corruption

Why is it important to have women in positions of power? Information on the relationship between gender and corruption may be incomplete. However, the general benefits of gender diversity are well-known as of now. The participation of women in the private sector has brought higher return rates, lower possibilities of bankruptcy, and other similar indicators of positive performance.

In the public sector, evidence shows that the presence of women in elective positions improves the allocation of public resources. On the other hand, it also increases the likelihood that the legislative priorities consider women and children’s interests.

The political implications of this study point to the need to promote gender equality (in general), as well as the presence of women in politics (in particular). Previous pieces of research have shown that a greater presence of women in governmental issues is associated with better results in education and health.

Anyway… Does Corruption Have a Gender?

In countries where corruption is the social norm, women who tend to follow social standards more than men may act almost as corruptly as men. Perhaps if women reach political decision-making positions, maybe they won’t feel the need to introduce codes of good behavior or fight against corruption.

In fact, Esarey and Chirillo (2013) established that the relationship between women in positions of political responsibility and corruption is practically nonexistent in authoritarian countries. A Congolese parliamentarian talked about this bluntly: “In the Congo, we all have to be a bit corrupt in order to survive. That’s just how the system works here”.

However, in countries where ‘good governance’ rules, increasing women’s political representation incites them to support legislative measures related to social norms. That’d explain why places such as Europe (where corruption obviously exists, but it’s not a social norm in the sense that not everyone accepts corrupt behavior), it’s important to encourage women’s political participation to fight against corruption.

“The world won’t be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything.”

-Albert Einstein-

Is there less corruption when women participate in politics? Are gender and corruption related? In 2015, Stensöta, Wängnerud, and Svensson carried out a study with which they tried to answer these questions. This investigation touches on the relationship between a greater number of women in parliament and a greater capacity to control corruption.

Are women less corrupt than men? The simple answer is yes. However, the relationship between gender and corruption has many nuances. First of all, why are women less corrupt? Are they less selfish? Do they have more self-control? Or do they not have the same opportunities to be corrupt?

This last question seems to have been answered in the recent study published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. Authors Chandan Jha of Le Moyne College and Sudipta Sarangi of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University showed that the relationship between gender and corruption isn’t caused by gender differences in social status. Actually, these authors suggest that corruption rates are unlikely to increase when women attain high social statuses.

In addition, this study led to another important discovery. A thorough analysis of 17 European countries found that the presence of women in local governments was negatively related to bribes.

“No science is immune to the infection of politics and the corruption of power.”

-Jacob Bronowski-

The Relationship between Gender and Corruption

Why is it important to have women in positions of power? Information on the relationship between gender and corruption may be incomplete. However, the general benefits of gender diversity are well-known as of now. The participation of women in the private sector has brought higher return rates, lower possibilities of bankruptcy, and other similar indicators of positive performance.

In the public sector, evidence shows that the presence of women in elective positions improves the allocation of public resources. On the other hand, it also increases the likelihood that the legislative priorities consider women and children’s interests.

The political implications of this study point to the need to promote gender equality (in general), as well as the presence of women in politics (in particular). Previous pieces of research have shown that a greater presence of women in governmental issues is associated with better results in education and health.

Anyway… Does Corruption Have a Gender?

In countries where corruption is the social norm, women who tend to follow social standards more than men may act almost as corruptly as men. Perhaps if women reach political decision-making positions, maybe they won’t feel the need to introduce codes of good behavior or fight against corruption.

In fact, Esarey and Chirillo (2013) established that the relationship between women in positions of political responsibility and corruption is practically nonexistent in authoritarian countries. A Congolese parliamentarian talked about this bluntly: “In the Congo, we all have to be a bit corrupt in order to survive. That’s just how the system works here”.

However, in countries where ‘good governance’ rules, increasing women’s political representation incites them to support legislative measures related to social norms. That’d explain why places such as Europe (where corruption obviously exists, but it’s not a social norm in the sense that not everyone accepts corrupt behavior), it’s important to encourage women’s political participation to fight against corruption.

“The world won’t be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything.”

-Albert Einstein-

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

Agerberg, M., Sundstrom, A., & Wangnerud, L. (2014, July). Why Regime Type affects the link between gender and corruption. In IPSA Congress, Montreal, July.

Esarey, J., & Chirillo, G. (2013). “Fairer sex” or purity myth? Corruption, gender, and institutional context. Politics & Gender, 9(4), 361-389.

Jha, C., & Sarangi, S. (2016). Social Media, Internet, and Corruption.

Jha, C. K., & Sarangi, S. (2017). Does social media reduce corruption?. Information Economics and Policy, 39, 60-71.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.