What We Can Learn from "A Beautiful Mind"

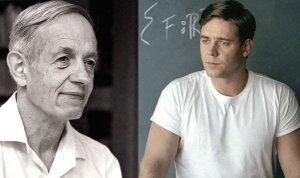

John Nash, the mathematical genius that inspired the amazing movie “A Beautiful Mind,” died in 2015.

Based on the novel of the same name by Sylvia Nasar and produced in 2001, the film was a great success which won four Oscars and countless followers. Starring Russell Crowe, the movie offers its audience a wonderful message in a simple way that invites us to look for ways to overcome our limitations, whatever they may be.

For those unfamiliar with John Nash’s story…

John Nash was 30 years old when doctors diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia. It was a tremendous illness that had severe effects on him.

He was a brilliant, outstanding, promising individual when it happened. However, nothing stopped him from chasing his dreams. After years of subjecting himself to cruel treatments to try to overcome his mental illness, John Nash managed to keep his symptoms at bay.

He learned to live with with his hallucinations. John heard voices, and saw things…but he could handle them.

Of course, he had to fight through the end of his days. It is very complicated to live without being able to discern what is real and what is not. However, Nash’s brilliant mind succeeded.

Nash won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994 for his game theory, which even now continues to be valid and useful in the strategic field. John fought his illness his whole life. And, yes, he won. He managed to lead a life completely different from what his illness dictated.

His death, just as his life, was unexpected. On May 23, 2015, Nash passed away along with his wife in a traffic accident.

An example of perseverance and hope

We owe him a lot, not only for his contribution to science but for telling us his story and returning to “the world of the sane” to teach us all that every mind is wonderful.

John held on to his intelligence and coexisted with the voices in his head despite their efforts to stifle him. His struggle was far from easy. However, he came to understand that the true path in his life lay in acceptance. And it showed.

Inspiration struck. He managed to create his own stable world in a constantly changing scene. And, what was at first a battle, ended up being a home to him in his development. Despite his limitations, Nash earned a position as a professor at MIT and was able to share the brilliance that his mental illness had once tried to stifle.

John Forbes Nash Jr. learned to live with schizophrenia throughout his life by applying the rule that “every problem has a solution.” This is a rule that, while it may not apply to every person with a mental illness, can be brought into every life in some way.

To live knowing that a large part of our pain is inevitable should be a premise we all follow. Undoubtedly, John gave us the key to enjoying life: accept, flow, and act.

So, can schizophrenia be cured, or not?

Sometimes, what someone needs is not a brilliant mind to speak but a patient heart to listen.

The investigative journalist Robert Whitaker found that, for a long time, Western Lapland in Finland had the highest rates of schizophrenia in the population. To give you an idea, about 70,000 people live there, and throughout the 1970s and early 80s, there were 25 or more new cases of schizophrenia there each year – that is double or, in some cases, triple the amount in the rest of Finland or Europe.

But in 1969, Yrjö Alanen arrived at the psychiatric hospital in Turku, Finland. At that time, there were very few psychiatrists that believed in the possibility of psychotherapy as a treatment for psychosis.

However, Alanen thought the hallucinations and paranoid delusions associated with patients with schizophrenic tendencies showed meaningful stories when analyzed carefully.

So, they started working on the task of listening to patients and their families.

Through this process, they created a new treatment model that they called the “Need Adapted Treatment Model (NATM).” This treatment keeps in mind that each person is unique and, thus requires a specific treatment adapted for their needs.

For example, some patients needed to be hospitalized while others did not. Moreover, there would be patients that benefited from low doses of psychiatric drugs (e.g. anxiolytics or antipsychotics) while others would not.

So, as we can see, they personalized and worked with each case as its own unique entity, becoming more and more aware of the needs of each patient and their families. Of course, they made decisions on treatment jointly, valuing a diversity of opinions.

Therapy sessions did not revolve around the reduction of psychotic symptoms, but instead centered on the past successes and achievements of the patient to try and strengthen their control over their life.

By doing this, patients do not lost their hope to be like others or to maintain “normality,” and they can look ahead instead of isolating themselves.

In recent years, Open Dialogue Therapy has transformed the “box of psychotic population” in Western Lapland. Spending on psychiatric services in the region has massively been reduced and, at present, is the sector with the lowest amount of spending on mental health in all of Finland. Twenty five new cases annually has become only two or three new cases.

So it is clear is that things can be done differently. There is another kind of treatment for those with schizophrenia or any other psychosis that guarantees a different life than what is expected for them.

So remember: there are always better ways of doing things. But if we as a society are sick, we will never come to see that there is a wonderful light at the end of the tunnel for everyone.

John Nash, the mathematical genius that inspired the amazing movie “A Beautiful Mind,” died in 2015.

Based on the novel of the same name by Sylvia Nasar and produced in 2001, the film was a great success which won four Oscars and countless followers. Starring Russell Crowe, the movie offers its audience a wonderful message in a simple way that invites us to look for ways to overcome our limitations, whatever they may be.

For those unfamiliar with John Nash’s story…

John Nash was 30 years old when doctors diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia. It was a tremendous illness that had severe effects on him.

He was a brilliant, outstanding, promising individual when it happened. However, nothing stopped him from chasing his dreams. After years of subjecting himself to cruel treatments to try to overcome his mental illness, John Nash managed to keep his symptoms at bay.

He learned to live with with his hallucinations. John heard voices, and saw things…but he could handle them.

Of course, he had to fight through the end of his days. It is very complicated to live without being able to discern what is real and what is not. However, Nash’s brilliant mind succeeded.

Nash won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994 for his game theory, which even now continues to be valid and useful in the strategic field. John fought his illness his whole life. And, yes, he won. He managed to lead a life completely different from what his illness dictated.

His death, just as his life, was unexpected. On May 23, 2015, Nash passed away along with his wife in a traffic accident.

An example of perseverance and hope

We owe him a lot, not only for his contribution to science but for telling us his story and returning to “the world of the sane” to teach us all that every mind is wonderful.

John held on to his intelligence and coexisted with the voices in his head despite their efforts to stifle him. His struggle was far from easy. However, he came to understand that the true path in his life lay in acceptance. And it showed.

Inspiration struck. He managed to create his own stable world in a constantly changing scene. And, what was at first a battle, ended up being a home to him in his development. Despite his limitations, Nash earned a position as a professor at MIT and was able to share the brilliance that his mental illness had once tried to stifle.

John Forbes Nash Jr. learned to live with schizophrenia throughout his life by applying the rule that “every problem has a solution.” This is a rule that, while it may not apply to every person with a mental illness, can be brought into every life in some way.

To live knowing that a large part of our pain is inevitable should be a premise we all follow. Undoubtedly, John gave us the key to enjoying life: accept, flow, and act.

So, can schizophrenia be cured, or not?

Sometimes, what someone needs is not a brilliant mind to speak but a patient heart to listen.

The investigative journalist Robert Whitaker found that, for a long time, Western Lapland in Finland had the highest rates of schizophrenia in the population. To give you an idea, about 70,000 people live there, and throughout the 1970s and early 80s, there were 25 or more new cases of schizophrenia there each year – that is double or, in some cases, triple the amount in the rest of Finland or Europe.

But in 1969, Yrjö Alanen arrived at the psychiatric hospital in Turku, Finland. At that time, there were very few psychiatrists that believed in the possibility of psychotherapy as a treatment for psychosis.

However, Alanen thought the hallucinations and paranoid delusions associated with patients with schizophrenic tendencies showed meaningful stories when analyzed carefully.

So, they started working on the task of listening to patients and their families.

Through this process, they created a new treatment model that they called the “Need Adapted Treatment Model (NATM).” This treatment keeps in mind that each person is unique and, thus requires a specific treatment adapted for their needs.

For example, some patients needed to be hospitalized while others did not. Moreover, there would be patients that benefited from low doses of psychiatric drugs (e.g. anxiolytics or antipsychotics) while others would not.

So, as we can see, they personalized and worked with each case as its own unique entity, becoming more and more aware of the needs of each patient and their families. Of course, they made decisions on treatment jointly, valuing a diversity of opinions.

Therapy sessions did not revolve around the reduction of psychotic symptoms, but instead centered on the past successes and achievements of the patient to try and strengthen their control over their life.

By doing this, patients do not lost their hope to be like others or to maintain “normality,” and they can look ahead instead of isolating themselves.

In recent years, Open Dialogue Therapy has transformed the “box of psychotic population” in Western Lapland. Spending on psychiatric services in the region has massively been reduced and, at present, is the sector with the lowest amount of spending on mental health in all of Finland. Twenty five new cases annually has become only two or three new cases.

So it is clear is that things can be done differently. There is another kind of treatment for those with schizophrenia or any other psychosis that guarantees a different life than what is expected for them.

So remember: there are always better ways of doing things. But if we as a society are sick, we will never come to see that there is a wonderful light at the end of the tunnel for everyone.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.