When Sigmund Freud Lost His Daughter Sophie

Written and verified by the psychologist Valeria Sabater

When Sigmund Freud lost his daughter Sophie, he was forced to change many of his theories about grief. He was fully aware that this pain and emptiness would never leave him. It may weaken over time, but wouldn’t be forgotten. At the same time, he understood that there was nowhere to shelter himself to relieve the suffering. The death of a child was, in his opinion, something inconceivable.

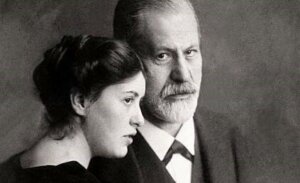

Sophie Freud was the fifth child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She was born on April 12th, 1893, and almost immediately became her father’s favorite. That child, almost without knowing why, softened the tyrannical and patriarchal character of the father of psychoanalysis. She was beautiful, resolute, and always determined to follow her own will beyond what her surroundings may have dictated to her.

She married Max Halberstadt, a photographer and portrait painter from Hamburg, at the age of 20. The 30-year-old wasn’t rich, nor was he distinguished or overly ambitious. Thus, Sigmund Freud was aware that his daughter might be in need. However, he didn’t object to the marriage and made his daughter promise to keep him informed of her problems and concerns.

That’s what Sophie did. However, no one could predict that her happiness (and that of her family) would be cut short and that she would die only six years into her marriage.

When Sigmund Freud lost his daughter Sophie

One year into their marriage, Sophie and Max Halberstadt had a child, Ernst Wolfgang. Sigmund Freud was fascinated by the little boy, and penned these words to his colleague Karl Abraham:

“My grandson Ernst is a charming little fellow who laughs attractively when you pay attention to him. He’s a decent and valuable creature in these times where only unleashed bestiality grows.”

The context of those comments was World War I, which was already raging in Europe. Sigmund Freud was one of the first public figures to warn society about this disconcerting and brutal movement that was germinating even in his native Vienna. However, his personal and family circle wouldn’t be affected until Hitler came to power in 1933.

Until then, Freud continued to develop his work while continuing to exchange correspondence with his daughter Sophie. On December 8, 1918, his second grandson, Heinz, was born. It was then that the young woman told her father that they were in financial trouble and that the arrival of that second son was a blessing, but also a problem.

Freud didn’t hesitate to offer her the help she needed. As we can read in Letters of Sigmund Freud, he also offered his daughter advice on the contraceptive methods of the time. However, they didn’t seem to be effective because, a year later, Sophie became pregnant again.

The third unwanted pregnancy

When Sophie wrote to her father, announcing this third unwanted pregnancy, and fearing his reply, her father replied as follows:

“If you think the news will make me very angry or dismayed, then you’re wrong. Accept this baby, don’t be disappointed. In a few days, you’ll receive some money which has come from my latest work.”

However, in 1920, Europe was in the grip of the Spanish flu. Sophie was very weakened by that third pregnancy and ended up being admitted to a hospital in January of that same year. She sadly died a few days later from an infection. When Sigmund Freud lost his daughter Sophie, he wrote about the impact of that experience.

He explained, for example, that he couldn’t find transportation to be with her in her final days. The only thing he could do was to go to her funeral and try to accept a loss he found no meaning or explanation to.

However, the most striking thing happened nine years after that loss. In a letter to one of her best friends and colleagues, Ludwig Binswanger, he wrote that he still hadn’t been able to come to terms with the experience.

“We know that the acute pain we feel after a loss will continue; it will also remain inconsolable and we will never find a replacement. No matter what happens, no matter what we do, the pain is always there. And that’s the way it should be. It’s the only way to perpetuate a love we don’t want to give up.”

-Letter from Sigmund Freud to Ludwig Binswanger-

Sigmund Freud and his grief

In Letters of Sigmund Freud, we can even read the letters that Freud and Dr. Arthur Lippmann from the Hamburg hospital sent to each other after Sophie’s death at the age of 26.

In them, the father of psychoanalysis regretted that effective contraception wasn’t yet available. Moreover, in these letters, he even lamented what he called “A foolish and inhuman law that forced women to continue with unwanted pregnancies”.

When Sigmund Freud lost his daughter Sophie, he tried to deal with the grief in his own way and dragged it out for more than 10 years, to the point that he had to reformulate the whole concept in his theories.

Eventually, he had to accept that both sadness and melancholy could be experienced when dealing with loss and that both states were acceptable. Even pain itself was a challenge compatible with survival. It was (and is) a stubborn bond that one refuses to abandon because it’s our way of holding on to the love of a loved one.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Freud, Sigmund (2016). “Cartas a sus hijos”, T. II, Ed. Paidós, 2016.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.