Wassily Kandinsky, a Life All about Color

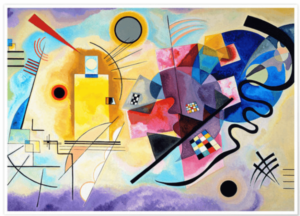

Wassily Kandinsky was the first painter to base his art on purely pictorial means of expression. Wassily abandoned the use of objects in his paintings in favor of abstraction.

Kandinsky was a multi-skilled artist. He wasn’t just a painter but also an engraver and writer. Throughout the world, this Russian artist is considered one of the creators of pure abstraction in modern art.

After successful leading edge art exhibitions, he founded the influential Munich group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider, 1911-14) and began to dedicate himself solely to abstract painting. His style evolved from his first fluid and elemental works to geometric and pictographic works.

Wassily Kandinsky: childhood and background

Kandinsky was born in his homeland Russia on December 4, 1866, in Moscow. He was born into a wealthy, multicultural home.

His mother was a Muscovite, one of his grandmothers was a Mongolian princess, and his father was a native of Kyakhta, a Siberian city near the Chinese border. Thus, from childhood, he grew up with a rich cultural heritage that was partly European and partly Asian.

His family was genteel and fond of travel. While still a child, he became acquainted with Venice, Rome, Florence, the Caucasus, and Crimea.

His mother had a strong musical inclination, while his father worked as a tea merchant. However, when Kandinsky was just five years old, his parents got divorced.

The boy moved to Odessa (Ukraine) to live with an aunt. There, he learned to play the piano and the cello in elementary school. In addition, he studied drawing with a private tutor.

From his childhood onward, he started experimenting with art. His childhood works reveal very specific color combinations, infused by his premise: “Each color lives by its mysterious life”.

Kandinsky’s youth

In 1886, he began studying law and economics at Moscow State University. The young man continued to experience unique feelings about color as he gazed at the city’s vivid architecture and collections of icons.

In 1889, the university sent him on an ethnographic mission (studying culture) to the Vologda province in the heavily-forested north. Kandinsky returned from this trip with an interest in the often wild and unrealistic styles of Russian folk art. That same year, he discovered the Rembrandts at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and continued his visual education with a trip to Paris.

By his own testimony, at this stage of his life, he had already lost much of his early enthusiasm for the social sciences. However, he continued to pursue his academic career and, in 1893, he was awarded a doctorate.

At first, he resisted his artistic inclination, considering that art was “a luxury forbidden to a Russian”. Finally, after teaching for a time at the university, he accepted a position as director of the photographic section of a Moscow printing company.

In 1892, Kandinsky married his cousin, Anna Chimyakina. Soon after, he accepted a position at the Moscow Law Faculty while he kept his artistic tastes a secondary pursuit.

However, two events led to an abrupt career change in 1896. The first occurred while he was attending an exhibition of French impressionists in Moscow, which was his first experience of non-representational art. The second event was when he listened to Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Bolshoi Theater. From this point on, Kandinsky’s life and career changed.

The start of his artistic career

In 1896, as he approached his 30th birthday, Kandinsky decided to abandon his law career and move to Munich. The language wasn’t a problem for him, since he’d learned German from his maternal grandmother as a child.

In Munich, he decided to dedicate himself full time to studying art. He enrolled at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, although much of his artistic learning was self-taught.

Kandinsky stated that Claude Monet’s work was one of his greatest inspirations. In Monet’s paintings, the subject played a secondary role, with color taking center stage.

It was as if reality and fairy tales were combined. That was the secret of Kandinsky’s early work, which was based on folk art and remained so even as his work became more complex over time.

Between 1902 and 1907, the artist was something of a nomad. He visited several different countries, including France, the Netherlands, Tunisia, Italy, and Russia. He finally settled in Murnau, Germany.

During his travels, he painted a series of alpine landscapes between 1908 and 1910. His famous work, The Blue Mountain, which explicitly described a scenic view of nature using colors, belongs to this period.

Unlike other artists of the time, his use of color on canvas was completely unusual. He used the color palette to express emotions rather than to give an accurate description of nature or other subjects.

Munich and the Blue Rider group

In 1909, he founded and became the president of the Munich New Artists’ Association. However, his more radical thoughts didn’t mesh well with those of more mainstream artists, which led to the group being dissolved in 1911.

This led to the formation of a new group, the Blue Rider, with like-minded artists. The group organized two exhibitions and even published an annual almanac. However, with the outbreak of World War I, Kandinsky returned to Russia.

“Lend your ears to music, open your eyes to painting, and… stop thinking! Just ask yourself whether the work has enabled you to ‘walk about’ into a hitherto unknown world. If the answer is yes, what more do you want?”

-Wassily Kandinsky-

The year 1910 was crucial for Kandinsky and the world of art. That year, Wassily Kandinsky revolutionized the art scene with his first abstract watercolor.

During this period, he published his treatise “On the Spiritual in Art” in The Blue Rider Almanac. In addition, he promoted abstract art and the free use of colors. Until that moment, color had been a purely functional tool at the service of the artist. That is, it served only as a complement to represent an object, a landscape, etc. Kandinsky took the plunge and broke with that purely functional use to give color total freedom.

Wassily Kandinsky and his return to Russia

At the end of the Russian Revolution, the artist held an important position in the People’s Commissariat for Education (government office) and the Moscow Academy. Upon returning to Russia, he became engrossed in Russian cultural politics. In addition, he assisted in art education and museum reform from 1918 to 1921.

He organized 22 museums and became the director of the Museum of Pictorial Culture. In 1920, he was appointed a professor at the University of Moscow.

Dedicating less time to painting, he devoted much of his time to teaching his artistic knowledge to others. The artist followed a program based on the analysis of shapes and colors in his classes.

In 1921, Kandinsky founded the Academy of Artistic Sciences and became its first director. However, at the end of that year, the Soviet attitude toward art changed. The radical members of the institute rejected Kandinsky’s ideas and expressionist vision of art. His peers judged him as too individualistic and, as a consequence, he decided to leave Russia.

Reception in Germany: Weimar period

In 1921, the architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Weimar Bauhaus art school, invited Kandinsky to Germany, who accepted the invitation.

The following year, Wassily taught painting classes for beginners as well as trained professionals. Kandinsky set about teaching them his color theory with new aspects of form psychology.

In 1926, he published his second theoretical book, Point and Line to Plane. This book described his development of forms study. The work emphasized geometric shapes: triangles, circles, semicircles, straight lines, and curves.

As he experimented further with color, his works underwent further changes over time. Works from this period highlighted individual geometric elements that paved the way for using cool colors.

In 1933, when the Nazis closed the Bauhaus art school, the artist settled in France.

Wassily Kandinsky and his time in the City of Lights

In Paris, he lived in a small apartment while he developed his creative skill. Most of his works from this period featured original color compositions, occasionally mixing sand with paint to give his paintings a rustic, grainy texture.

His Parisian period paintings are splendid in their use of color, rich in invention, and charming in humor.

“The true work of art is born from the artist: a mysterious, enigmatic, and mystical creation. It detatches itself from him, it acquires an autonomous life, becomes a personality, an independent subject, animated with spiritual breath, the living subject of a real existence of being.”

-Wassily Kandinsky-

In July 1937, accompanied by other contemporary artists, he presented his work at the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. Although the exhibition was well-attended, 57 of his works were confiscated by the Nazis.

The master of color and abstract art died of cerebrovascular disease in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, on December 13, 1944. But his memory lives on in his work. His paintings will always be timeless.

Kandinsky continues to be highly regarded for his paintings and for being one of the creators of abstract art. He invented a language of abstract forms with which he replaced nature’s forms.

Wassily wanted to reflect the universe in his own visionary world. He felt that painting had the same power as music and that colors should correspond to the vibrations of the human soul.

Wassily Kandinsky was the first painter to base his art on purely pictorial means of expression. Wassily abandoned the use of objects in his paintings in favor of abstraction.

Kandinsky was a multi-skilled artist. He wasn’t just a painter but also an engraver and writer. Throughout the world, this Russian artist is considered one of the creators of pure abstraction in modern art.

After successful leading edge art exhibitions, he founded the influential Munich group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider, 1911-14) and began to dedicate himself solely to abstract painting. His style evolved from his first fluid and elemental works to geometric and pictographic works.

Wassily Kandinsky: childhood and background

Kandinsky was born in his homeland Russia on December 4, 1866, in Moscow. He was born into a wealthy, multicultural home.

His mother was a Muscovite, one of his grandmothers was a Mongolian princess, and his father was a native of Kyakhta, a Siberian city near the Chinese border. Thus, from childhood, he grew up with a rich cultural heritage that was partly European and partly Asian.

His family was genteel and fond of travel. While still a child, he became acquainted with Venice, Rome, Florence, the Caucasus, and Crimea.

His mother had a strong musical inclination, while his father worked as a tea merchant. However, when Kandinsky was just five years old, his parents got divorced.

The boy moved to Odessa (Ukraine) to live with an aunt. There, he learned to play the piano and the cello in elementary school. In addition, he studied drawing with a private tutor.

From his childhood onward, he started experimenting with art. His childhood works reveal very specific color combinations, infused by his premise: “Each color lives by its mysterious life”.

Kandinsky’s youth

In 1886, he began studying law and economics at Moscow State University. The young man continued to experience unique feelings about color as he gazed at the city’s vivid architecture and collections of icons.

In 1889, the university sent him on an ethnographic mission (studying culture) to the Vologda province in the heavily-forested north. Kandinsky returned from this trip with an interest in the often wild and unrealistic styles of Russian folk art. That same year, he discovered the Rembrandts at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and continued his visual education with a trip to Paris.

By his own testimony, at this stage of his life, he had already lost much of his early enthusiasm for the social sciences. However, he continued to pursue his academic career and, in 1893, he was awarded a doctorate.

At first, he resisted his artistic inclination, considering that art was “a luxury forbidden to a Russian”. Finally, after teaching for a time at the university, he accepted a position as director of the photographic section of a Moscow printing company.

In 1892, Kandinsky married his cousin, Anna Chimyakina. Soon after, he accepted a position at the Moscow Law Faculty while he kept his artistic tastes a secondary pursuit.

However, two events led to an abrupt career change in 1896. The first occurred while he was attending an exhibition of French impressionists in Moscow, which was his first experience of non-representational art. The second event was when he listened to Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Bolshoi Theater. From this point on, Kandinsky’s life and career changed.

The start of his artistic career

In 1896, as he approached his 30th birthday, Kandinsky decided to abandon his law career and move to Munich. The language wasn’t a problem for him, since he’d learned German from his maternal grandmother as a child.

In Munich, he decided to dedicate himself full time to studying art. He enrolled at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, although much of his artistic learning was self-taught.

Kandinsky stated that Claude Monet’s work was one of his greatest inspirations. In Monet’s paintings, the subject played a secondary role, with color taking center stage.

It was as if reality and fairy tales were combined. That was the secret of Kandinsky’s early work, which was based on folk art and remained so even as his work became more complex over time.

Between 1902 and 1907, the artist was something of a nomad. He visited several different countries, including France, the Netherlands, Tunisia, Italy, and Russia. He finally settled in Murnau, Germany.

During his travels, he painted a series of alpine landscapes between 1908 and 1910. His famous work, The Blue Mountain, which explicitly described a scenic view of nature using colors, belongs to this period.

Unlike other artists of the time, his use of color on canvas was completely unusual. He used the color palette to express emotions rather than to give an accurate description of nature or other subjects.

Munich and the Blue Rider group

In 1909, he founded and became the president of the Munich New Artists’ Association. However, his more radical thoughts didn’t mesh well with those of more mainstream artists, which led to the group being dissolved in 1911.

This led to the formation of a new group, the Blue Rider, with like-minded artists. The group organized two exhibitions and even published an annual almanac. However, with the outbreak of World War I, Kandinsky returned to Russia.

“Lend your ears to music, open your eyes to painting, and… stop thinking! Just ask yourself whether the work has enabled you to ‘walk about’ into a hitherto unknown world. If the answer is yes, what more do you want?”

-Wassily Kandinsky-

The year 1910 was crucial for Kandinsky and the world of art. That year, Wassily Kandinsky revolutionized the art scene with his first abstract watercolor.

During this period, he published his treatise “On the Spiritual in Art” in The Blue Rider Almanac. In addition, he promoted abstract art and the free use of colors. Until that moment, color had been a purely functional tool at the service of the artist. That is, it served only as a complement to represent an object, a landscape, etc. Kandinsky took the plunge and broke with that purely functional use to give color total freedom.

Wassily Kandinsky and his return to Russia

At the end of the Russian Revolution, the artist held an important position in the People’s Commissariat for Education (government office) and the Moscow Academy. Upon returning to Russia, he became engrossed in Russian cultural politics. In addition, he assisted in art education and museum reform from 1918 to 1921.

He organized 22 museums and became the director of the Museum of Pictorial Culture. In 1920, he was appointed a professor at the University of Moscow.

Dedicating less time to painting, he devoted much of his time to teaching his artistic knowledge to others. The artist followed a program based on the analysis of shapes and colors in his classes.

In 1921, Kandinsky founded the Academy of Artistic Sciences and became its first director. However, at the end of that year, the Soviet attitude toward art changed. The radical members of the institute rejected Kandinsky’s ideas and expressionist vision of art. His peers judged him as too individualistic and, as a consequence, he decided to leave Russia.

Reception in Germany: Weimar period

In 1921, the architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Weimar Bauhaus art school, invited Kandinsky to Germany, who accepted the invitation.

The following year, Wassily taught painting classes for beginners as well as trained professionals. Kandinsky set about teaching them his color theory with new aspects of form psychology.

In 1926, he published his second theoretical book, Point and Line to Plane. This book described his development of forms study. The work emphasized geometric shapes: triangles, circles, semicircles, straight lines, and curves.

As he experimented further with color, his works underwent further changes over time. Works from this period highlighted individual geometric elements that paved the way for using cool colors.

In 1933, when the Nazis closed the Bauhaus art school, the artist settled in France.

Wassily Kandinsky and his time in the City of Lights

In Paris, he lived in a small apartment while he developed his creative skill. Most of his works from this period featured original color compositions, occasionally mixing sand with paint to give his paintings a rustic, grainy texture.

His Parisian period paintings are splendid in their use of color, rich in invention, and charming in humor.

“The true work of art is born from the artist: a mysterious, enigmatic, and mystical creation. It detatches itself from him, it acquires an autonomous life, becomes a personality, an independent subject, animated with spiritual breath, the living subject of a real existence of being.”

-Wassily Kandinsky-

In July 1937, accompanied by other contemporary artists, he presented his work at the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. Although the exhibition was well-attended, 57 of his works were confiscated by the Nazis.

The master of color and abstract art died of cerebrovascular disease in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, on December 13, 1944. But his memory lives on in his work. His paintings will always be timeless.

Kandinsky continues to be highly regarded for his paintings and for being one of the creators of abstract art. He invented a language of abstract forms with which he replaced nature’s forms.

Wassily wanted to reflect the universe in his own visionary world. He felt that painting had the same power as music and that colors should correspond to the vibrations of the human soul.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Kandinsky, W. (2016). De lo espiritual en el arte. Wassily Kandinsky.

- Martínez Benito, J. (2011). Kandinsky y la abstracción: nuevas interpretaciones (Doctoral dissertation).

- Silenzi, M. (2009). El juicio estético sobre lo bello: Lo sublime en el arte y el pensamiento de Kandinsky. Andamios, 6(11), 287-302.

- Düchting, H. (1990). Wassily Kandinsky: 1866-1944 una revolución pictórica. Benedikt Taschen.

- García, G. I. (2002). Utopia e ideologia: Kandinsky y la modernizacion del espacio pictorico. Káñina, 26(2), 135-146.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.