The Penfield Homunculus - Representing our Brain in a Human Form

Written and verified by the psychologist Gema Sánchez Cuevas

Our brain is quite extraordinary. We have been studying it for years and we haven’t yet discovered all its possibilities. It is like the universe – infinite and full of surprises. Maybe that’s why when new functions or areas of the brain are discovered, we try to simplify the findings. That’s what happened with the well-known Penfield Homunculus.

The Penfield Homunculus was first referred to by Dr. Wilder Penfield between the 1940s and the 1950s. This Canadian neurosurgeon sought to explain and cure neurological diseases such as epilepsy. During his work, as the brain doesn’t feel pain, he applied electric shocks to different areas of patient’s brains. He then asked his patients, who were awake, what they felt.

By applying these shocks, he discovered a small area of the brain where a sensory map of our body was established. This map reflected the sensitivity of each of the parts of our anatomy. He decided to represent this area as if it were a human form, giving rise to Penfield’s Homunculus.

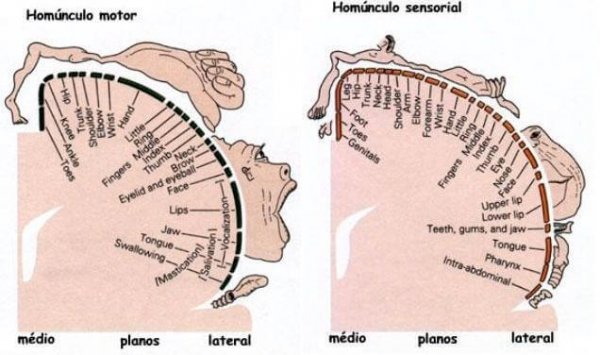

What makes this representation special is that it shows that we have areas in our body that are more sensitive to stimulation than others. This gives rise to a deformed, disproportionate man. The most sensitive areas are larger than those that are less sensitive. But this is not all. Shortly after, it was discovered that there was not only one man living in our head, but two. One sensory and one motor, both very different but with points in common.

“As long as the brain is a mystery, the universe will continue to be one too”

-Santiago Ramon y Cajal-

Characteristics and functions of Penfield’s Homunculus

We now know that there are two Penfield Homunculi, one sensory and one motor, so let’s find out a bit more about them.

Motor homunculus or primary motor cortex

The motor homunculus or primary motor cortex is found right next to the sensory homunculus. We can find it exactly in the central groove of the frontal cortex. This area is the most important one for the physical functioning of our body.

In collaboration with other areas, such as the supplementary motor cortex, and taking into account the input received from the thalamus, the motor homunculus elaborates and performs the physical movements our body makes. That is why its appearance is slightly different from that of the sensory homunculus. Its mouth, eyes and especially its hands are enormous, due to the greater uniqueness in the location of the receptors and motor nerves.

A curious aspect of this area is that it develops differently in each human being. This implies that the speed of its development is unique and personal. It depends on which parts of the body are used most and how they will have better motor skills or training in general.

Sensory homunculus or primary somesthetic cortex

The sensory homunculus represents the primary somesthetic cortex (the tactile pressure or pain sensitivity in our body). It is located in the parietal lobe, just where it joins with the frontal lobe. To explain it another way, the sensory homunculus comprises areas 1, 2, and 3 of Broadman.

In this area our body outline is represented contralaterally as it is laterally inverted. This means that the right hand representation of our body is represented in the left of this brain area, and the left representation in the right part.

It should be noted that this sensory area receives most of our body’s projections of information through the thalamus. The thalamus is the area which integrates the different sensory sources of our brain, making us perceive our world in an integrated, not separated, way according to whatever sense is perceiving it.

Furthermore, the sensory homunculus is in charge of our own perception, in other words, of the state of our inner body. It informs us of our posture and the state of our organs and our muscles. And, as strange as it may seem, of how we look from the inside.

All of this is vital for our emotional well-being. This is why the lips and the extremities are more sensitive. Caresses, kisses and hugs are very important in terms of the universe of emotions that we feel.

The phantom limb, the main disease of Penfield’s Homunculus

If Penfield’s Homunculus is affected in any way, either on a sensory or motor level, it can lead to a curious disease: the phantom limb. When suffering from this disease, the brain perceives the same sensations as that of an amputated limb.

A derivative of the phantom limb is phantom pain. With the phantom pain, the sensory area that represents the part of the amputated body sends us pain sensations from our brain. This means that even if the limb is amputated, due to the activity of the neurons of the sensory homunculus, we won’t stop feeling it. As we can see, a discovery driven by curiosity through electrical stimulation of the brain has opened up a whole universe of possibilities. Thanks to all of this, we have realized the importance of each touch on our skin, in our brain and for our emotional development.

Bibliographical references:

Abril Alonso, Águeda del. (2005) Biological foundations of behavior.Madrid

Sanz and Torres.Carlson, N. (2014). Physiology of behavior. Madrid

Pearson.Haines D.E. (2002) Principles of Neuroscience. Madrid: Elsevier Spain S.A.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

Abril Alonso, Águeda del. (2005) Fundamentos biológicos de la conducta. Madrid: Sanz y Torres.

Carlson, N. (2014). Fisiología de la conducta. Madrid: Pearson.

Haines D.E. (2002) Principios de Neurociencia. Madrid: Elsevier España S.A.

Schott, GD (1993). El homúnculo de Penfield: una nota sobre cartografía cerebral. Journal of Neurology Neurocirugía y psiquiatría , 56 (4), 329–333. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.56.4.329

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.