Max Eitingon and the Pillars of Psychoanalytical Education

Max Eitingon was one of the first and most important first-generation physicians and psychoanalysts. He made fundamental contributions to psychoanalytical education and training, and his work altered the current of thought in the field.

Psychoanalysts undergo a different type of training to other mental health professionals. In the early days of psychoanalysis, there were no training programs for the study of this particular field. Instead, psychoanalysts had to have a degree in medicine. In other words, psychoanalysts were, first and foremost, doctors.

This practice continues in some countries today, although it’s not the only way to enter the field of psychoanalysis. Thanks to the work of Max Eitingon and other prominent figures, the future of psychoanalysis changed forever, branching off from the world of medicine and becoming a field in its own right.

One of the major differences between a psychologist and psychoanalyst is that the former requires a university degree in the field of psychology. Psychoanalysts, on the other hand, are often trained by undergoing their own training analysis. Max Eitingon played a fundamental role in bringing about this change.

In this article, we want to shed some light on these issues and discover more about the life and work of Max Eitingon.

“The feeling of triumph on being liberated is too strongly mixed with sorrow, for in spite of everything, I still greatly loved the prison from which I have been released.”

-Sigmund Freud in a letter to Max Eitingon-

Max Eitingon: the early years

Max Eitingon was born in the town of Mogilev, Belarus on June 26, 1881. He came from a family of Orthodox Jews of very good social standing. His father, Chaim Eitingon, was a wealthy merchant. He began his career in the sugar business, before later moving into the fur trade. Max had two sisters and two brothers, and was the second oldest of five children.

The family settled in Germany when Max was just 12 years old. He was shy and had a severe stutter. As a result of his stutter, he dropped out of high school but later took classes in art history and philosophy at the prestigious universities of Halle, Heidelberg, and Marburg.

In 1902, he began studying medicine in Leipzig, after taking high school equivalency tests to complete his studies. Subsequently, he found a job in Zurich, as an assistant to Eugene Bleuler. While he was there, he also met Carl Gustav Jung for the first time. Of the three, Eitingon was the first to reach out to Sigmund Freud, traveling to Vienna in 1907 for their first meeting.

Eitingon and psychoanalysis

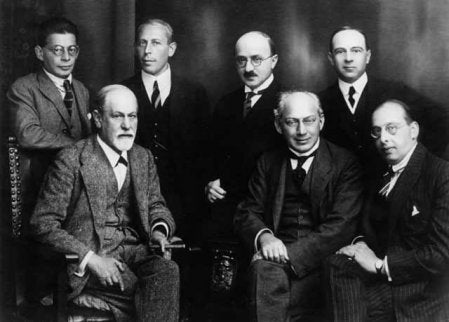

Max Eitingon began attending the meetings of the Vienna Psychological Society. There, he made an interesting speech that caught the attention of Sigmund Freud. As a result of this speech, the two met to discuss a particularly interesting case. On impulse, Max Eitingon and the father of psychoanalysis decided to carry out one of the first training analyses in history. They did it in stages, conducting their sessions between 1908 and 1909, during evening walks together.

His meeting with Sigmund Freud marked a before and after in the life of Max Eitingon. From that moment on, the pair formed an unbreakable bond, which lasted until Freud’s death. Eitingon became one of his closest “confidants”. On more than one occasion, he entrusted him to manage crises within various different psychoanalytical societies.

However, not everyone held Eitingon in the same regard, as disagreements began to erupt amongst the psychoanalysts of the time. For Carl Jung, Eitingon was someone of little consequence, while Otto Rank was firmly opposed to his joining the Secret Committee, which he did in 1919. Max was never a great psychoanalytical theorist but remained a staunch supporter of his teacher, and was charged with implementing his basic techniques.

Notable contributions

Along with Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon founded the Berlin Psychoanalytic Polyclinic, contributing considerable financial resources to the company. He also financially supported The International Journal of Psychoanalysis.

The Polyclinic later became the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, an institution whose goal was to provide a structured training program for psychoanalysts.

The three great pillars of education, as described by Sigmund Freud and implemented with great consistency by Max Eitingon, were the following:

- The introduction of the training psychoanalysis. This is when the psychoanalysis is conducted by someone aspiring to become a psychoanalyst. The goal is for the person to resolve their unconscious conflicts and learn the technique.

- Complementary training through structured seminars. In psychoanalysis, participation in seminars or study groups is essential for interacting with peers and increasing one’s aptitude.

- Supervision and presentation of cases. Their peers, to whom they had to present the cases they worked on, supervised each psychoanalyst.

These three pillars remain intact nowadays within the field of classical psychoanalysis. Max Eitingon and Sigmund Freud remained close friends until Freud’s death in 1939. Eitingon himself died just four years later, in Jerusalem. However, he left a lasting impact on the field of psychoanalysis, and on the training of future psychoanalysts.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Infante, J. A. (1968). “Algunas reflexiones acerca de la relación analítica”. Revista de psicoanálisis, 25(3-4), 767-775.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.