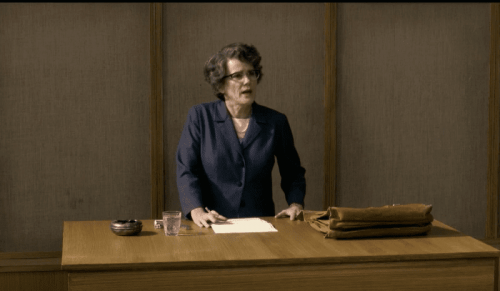

Johanna Arendt, A Pluralist Thinker

Johanna Arendt was one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century. Even though some labeled her as a “philosopher,” she rejected such a categorization. Perhaps because it’s too conclusive and limited for an intellectual with broad interests.

You could say that Johanna Arendt was one of the greatest experts on the “Jewish question“. Unlike other thinkers, she approached the subject with great breadth and critical sense, even though she was Jewish herself.

“The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after their revolution.”

-Hannah Arendt-

Her work The Origins of Totalitarianism is a true classic of political theory. In it, she exposes the historical development of anti-Semitism, racism, and imperialism. In the end, she describes what she calls “total domination,” basically embodied within Nazism and Stalinism.

A bright young woman

Hannah Arendt was born on October 14, 1906, in Linder-Limmen, Germany. Her family was Jewish and originally from Linden, the region of Prussia that later became a part of Russia.

Arendt’s father was an engineer who died of syphilis when she was just seven years old. And her mother, Martha Cohn, was a woman of liberal ideas. She wanted to give her daughter the same education the boys at the time received.

From an early age, Hannah Arendt showed signs of having great intellectual abilities and a rebellious character. Some say that, at the age of 14, she had already read the works of Emmanuel Kant and Karl Jaspers. Of course, they expelled her from school for “disciplinary issues” at age 17.

Then, Hannah traveled alone to Berlin, where she took courses on theology and philosophy. She began studying on her own and took and passed the entrance exam to the University of Marburg at the ripe age of 18.

Johanna Arendt, a Jewish intellectual

Martin Heidegger, a popular man, was one of Arendt’s teachers. The two fell in love and began a secret affair. He was married and already had children. The situation became unsustainable for Hannah, who then moved for a semester to the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg.

There, she obtained a Doctorate in Philosophy in 1928, after taking classes with Edmund Husserl. Karl Jaspers was the tutor of her thesis and later became one of her closest friends. At the time, she was also a friend of many of the most notable philosophers of her time.

The progressive rise of Nazism began with a gradual increase in anti-Semitism. Hannah Arendt used her own house to help many children and young people flee. In 1933, she was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned for eight days. She then fled to France, where she met with her first husband, Günther Stern.

A stateless thinker

Johanna Arendt was one of the few European intellectuals who radically spoke against Nazism from the very beginning, unlike other philosophers who sought to reconcile with the new regime.

In 1937, Hannah divorced Günther and in the same year, the German government withdrew her nationality. She managed to get her mother out of Germany in 1939. In 1940, she married Heinrich Blücher. Then, shortly thereafter, she was sent to a concentration camp in France for the crime of being German, even though she wasn’t. She managed to escape from there and, along with her husband and mother, immigrated to the United States.

Once in the United States, she worked as a journalist, a trade she already had experience with as she practiced it in Europe. In 1951, she became a US citizen, although she always used to say that her heart was tied to Germany by language, art, and poetry.

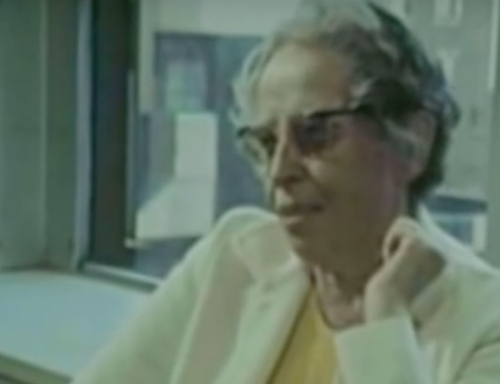

Johanna Arendt had a brilliant trajectory

When she became a US citizen, she “freed” herself from her stateless status. Actually, she said that having a citizenship was the “right to have rights”. Then, she had a brilliant career and wrote her greatest works in the United States.

In 1961, she worked as a correspondent for The New Yorker and reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal. The article bore “The banality of evil” as subtitle and it was very controversial.

In 1959, she became the first woman to teach at Princeton University. In 1963, she became a professor at the University of Chicago and worked at other academic centers thereafter.

Her beloved husband died in 1970. Four years later, Hannah suffered a heart attack she recovered from. So, she continued working until 1975 when a second heart attack took her life during an academic meeting.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Arendt, H. (2005). Arendt sobre Arendt. H. Arendt, De la historia a la acción. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.