How Good People Turn Evil: The Stanford Prison Experiment

“The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil” is the title of a book by Philip Zimbardo. In it, he presents his Stanford prison experiment, one of the most significant in the entire history of psychology.

The results changed how we view human beings. And they also influenced our understanding of how important our environment is and the role we play in our behaviors and attitudes.

In the book, Zimbardo asks some questions. What makes a good person act evilly? How can you seduce a moral person into acting immorally? Where’s the line separating good from bad, and who’s in danger of crossing it?

Before we try to find out, let’s learn a little more about what exactly the Stanford prison experiment was.

The Origins of the Stanford Prison Experiment

A professor at Stanford University, Philip Zimbardo wanted to research humans in a context where they lacked freedom. To achieve that, Zimbardo proposed simulating a prison using unused university space.

After making the area like a jail, Zimbardo had to fill it with “prisoners” and “guards.” So, Zimbardo recruited students for his experiment. They would get a small amount of money if they were willing to play these roles.

The experiment had 24 students, who they assigned to two groups (prisoners and guards), randomly. He wanted to increase the feeling of realism and achieve more immersion in those roles.

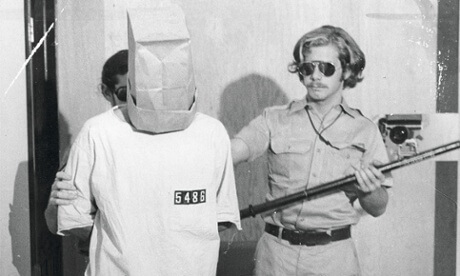

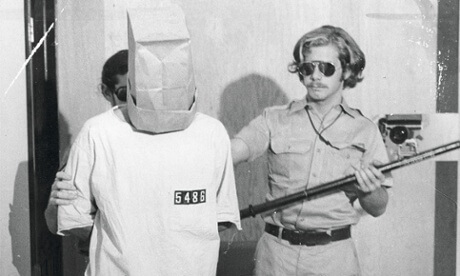

So, he had them go through a detention process (they had help from the police). Then, the simulated Stanford prison dressed them all like prisoners and replaced their names with identification numbers.

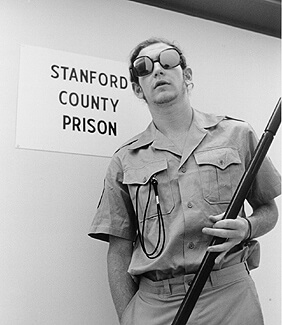

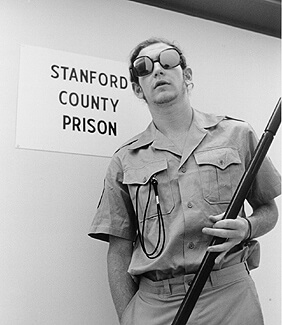

They gave the guards a uniform and sunglasses to encourage their role of authority.

Evil in the Stanford Prison

At the beginning of the Stanford prison experiment, most prisoners treated the situation as a game. So their immersion in their roles was very low.

But the guards needed to reaffirm their authority and have the prisoners act like prisoners. So, they started to do constant recounts and exercise an unfair amount of control.

The guards started to force the prisoners to follow certain rules during the recounts. Things like singing out their identification number. Also, if they disobeyed that order, they had to do push-ups.

These “games,” or orders, were harmless at first. By the second day, they became real, violent humiliations of the prisoners by the guards.

The guards punished the prisoners who got no food or sleep. For example, they would put them in a closet for hours. Or they would force them to stay standing up, naked.

The guards even got to the point of forcing them to pretend they were giving oral sex to the others. Because of this harassment, the prisoners forgot they were students taking part in an experiment. They started to think they were prisoners.

They had to cancel the Stanford prison experiment on the sixth day. Why? The violence that came from the students completely getting immersed in their roles.

There’s one question that immediately comes to mind. “How did the guards reach that level of evil with the prisoners?”

Conclusions: The Power of their Situation

After observing the behavior of the guards, Zimbardo tried to identify some variables. He wanted to understand what had made a normal group of students — without pathologies — act the way they did.

We can’t chalk up the evil of their behavior to the fact that the student guards were evil. This is because the makeup of each group was random.

In fact, before the experiment, they took a test related to violence. The results were clear: they didn’t tolerate violence, or only in very few situations.

So, the factor must have been something intrinsic to the experiment. Zimbardo started to think it was the strength of the situation he created in that prison. That it was the circumstances that pushed the peaceful students to act evil.

That’s strange because it’s true that we tend to think evil is a factor of disposition. That is, there are good people and bad people independent of the role or circumstances they’re given.

We tend to think the force of disposition, or personality, is more powerful than circumstances or roles. In this sense, Zimbardo’s experiment ended up telling us the opposite. Hence the revolutionary extent of the results.

The situation, along with the awareness a person has of their context, is extremely important. It’s what brings a person to act one way or another.

Sometimes the situation will push us to carry out a violent or evil act. So, if we’re not conscious of that, we won’t be able to do anything to avoid it.

Dehumanization in the Standford Prison Experiment

In the Stanford prison experiment, Zimbardo created a perfect context for the prisoners to feel dehumanized. They were made to feel this way in the guards’ eyes too.

This dehumanization comes from multiple factors. One, for example: is the imbalance of power between guards and prisoners. Or, the way the guards started to see the prisoners as a general group. And especially the substitution of their names for identification numbers, etc.

All this caused the guards to see the prisoners as just that, prisoners. They stopped seeing them as humans they could empathize with.

People who, in reality, out of the simulated context of the experiment, shared an important role with them. They were all students.

The Banality of Goodness and Evil

There’s one conclusion Zimbardo leaves us in his book. There aren’t any demons or heroes, or at least less than we think there are. Instead, evil and goodness must be more of a product of circumstance.

They aren’t as related to personality or childhood values as we think. This, deep down, is an optimistic message. Just about anyone can commit an evil act. But, at the same time, every person can also act heroically.

There’s only one thing we have to do to prevent the first case. We have to identify the characteristics of the situation or our role that might make us act evil.

Zimbardo wrote us this “anti-evil” handbook. With it, we can go against the pressures of any situation. It’s become so popular a concept, that there’s even a major movie that re-envisions it.

One question we might stick around and reflect on is about a certain situation we’ve all found ourselves in.

When we determine someone is acting evilly, how do we evaluate it? Do we evaluate their situation and their pressures, or do we simply categorize them as evil?

“The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil” is the title of a book by Philip Zimbardo. In it, he presents his Stanford prison experiment, one of the most significant in the entire history of psychology.

The results changed how we view human beings. And they also influenced our understanding of how important our environment is and the role we play in our behaviors and attitudes.

In the book, Zimbardo asks some questions. What makes a good person act evilly? How can you seduce a moral person into acting immorally? Where’s the line separating good from bad, and who’s in danger of crossing it?

Before we try to find out, let’s learn a little more about what exactly the Stanford prison experiment was.

The Origins of the Stanford Prison Experiment

A professor at Stanford University, Philip Zimbardo wanted to research humans in a context where they lacked freedom. To achieve that, Zimbardo proposed simulating a prison using unused university space.

After making the area like a jail, Zimbardo had to fill it with “prisoners” and “guards.” So, Zimbardo recruited students for his experiment. They would get a small amount of money if they were willing to play these roles.

The experiment had 24 students, who they assigned to two groups (prisoners and guards), randomly. He wanted to increase the feeling of realism and achieve more immersion in those roles.

So, he had them go through a detention process (they had help from the police). Then, the simulated Stanford prison dressed them all like prisoners and replaced their names with identification numbers.

They gave the guards a uniform and sunglasses to encourage their role of authority.

Evil in the Stanford Prison

At the beginning of the Stanford prison experiment, most prisoners treated the situation as a game. So their immersion in their roles was very low.

But the guards needed to reaffirm their authority and have the prisoners act like prisoners. So, they started to do constant recounts and exercise an unfair amount of control.

The guards started to force the prisoners to follow certain rules during the recounts. Things like singing out their identification number. Also, if they disobeyed that order, they had to do push-ups.

These “games,” or orders, were harmless at first. By the second day, they became real, violent humiliations of the prisoners by the guards.

The guards punished the prisoners who got no food or sleep. For example, they would put them in a closet for hours. Or they would force them to stay standing up, naked.

The guards even got to the point of forcing them to pretend they were giving oral sex to the others. Because of this harassment, the prisoners forgot they were students taking part in an experiment. They started to think they were prisoners.

They had to cancel the Stanford prison experiment on the sixth day. Why? The violence that came from the students completely getting immersed in their roles.

There’s one question that immediately comes to mind. “How did the guards reach that level of evil with the prisoners?”

Conclusions: The Power of their Situation

After observing the behavior of the guards, Zimbardo tried to identify some variables. He wanted to understand what had made a normal group of students — without pathologies — act the way they did.

We can’t chalk up the evil of their behavior to the fact that the student guards were evil. This is because the makeup of each group was random.

In fact, before the experiment, they took a test related to violence. The results were clear: they didn’t tolerate violence, or only in very few situations.

So, the factor must have been something intrinsic to the experiment. Zimbardo started to think it was the strength of the situation he created in that prison. That it was the circumstances that pushed the peaceful students to act evil.

That’s strange because it’s true that we tend to think evil is a factor of disposition. That is, there are good people and bad people independent of the role or circumstances they’re given.

We tend to think the force of disposition, or personality, is more powerful than circumstances or roles. In this sense, Zimbardo’s experiment ended up telling us the opposite. Hence the revolutionary extent of the results.

The situation, along with the awareness a person has of their context, is extremely important. It’s what brings a person to act one way or another.

Sometimes the situation will push us to carry out a violent or evil act. So, if we’re not conscious of that, we won’t be able to do anything to avoid it.

Dehumanization in the Standford Prison Experiment

In the Stanford prison experiment, Zimbardo created a perfect context for the prisoners to feel dehumanized. They were made to feel this way in the guards’ eyes too.

This dehumanization comes from multiple factors. One, for example: is the imbalance of power between guards and prisoners. Or, the way the guards started to see the prisoners as a general group. And especially the substitution of their names for identification numbers, etc.

All this caused the guards to see the prisoners as just that, prisoners. They stopped seeing them as humans they could empathize with.

People who, in reality, out of the simulated context of the experiment, shared an important role with them. They were all students.

The Banality of Goodness and Evil

There’s one conclusion Zimbardo leaves us in his book. There aren’t any demons or heroes, or at least less than we think there are. Instead, evil and goodness must be more of a product of circumstance.

They aren’t as related to personality or childhood values as we think. This, deep down, is an optimistic message. Just about anyone can commit an evil act. But, at the same time, every person can also act heroically.

There’s only one thing we have to do to prevent the first case. We have to identify the characteristics of the situation or our role that might make us act evil.

Zimbardo wrote us this “anti-evil” handbook. With it, we can go against the pressures of any situation. It’s become so popular a concept, that there’s even a major movie that re-envisions it.

One question we might stick around and reflect on is about a certain situation we’ve all found ourselves in.

When we determine someone is acting evilly, how do we evaluate it? Do we evaluate their situation and their pressures, or do we simply categorize them as evil?

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.