Franco Basaglia: A Groundbreaking Psychiatrist

Franco Basaglia was ahead of his time. This Italian psychiatrist came up with a new, revolutionary approach to psychiatry. In fact, the World Health Organization says that Basaglia’s work is key to understanding psychiatry as it is today.

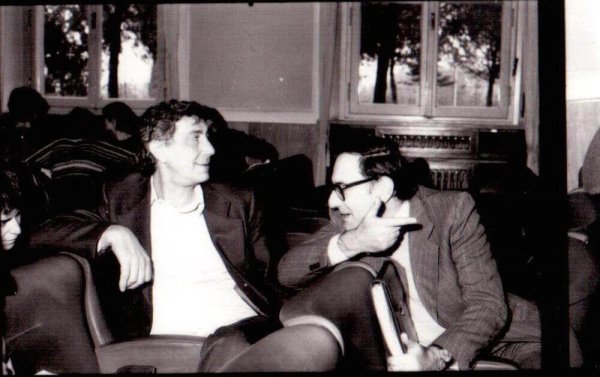

Along with Ronald D. Laing and David G. Cooper, Franco Basaglia is considered one of the fathers of “anti-psychiatry”. Many of his books have become classics, been translated into various languages, and read by many generations.

But Basaglia wasn’t just a meticulous scientist. He was also a humanist and activist. He fought back against traditional psychiatry, not just because its methods weren’t effective, but also due to his deep, ethical convictions. Today, his legacy lives on.

The Early Life of Franco Basaglia

Basaglia was born in Venice, Italy, in 1924 to a relatively wealthy family. He had a peaceful childhood. At the age of 19, he began studying at the school of medicine at the University of Padua.

He also became involved in the anti-fascist movement in his country, which led to his imprisonment in 1944 and 1945. The time he spent in prison made him become a fierce advocate against forced confinement.

Franco Basaglia earned his psychiatry degree in 1950. Eight years later, he became a professor at the University of Padua. Just three years later, he quit that job and moved to Gorizia, where he was the director of the local psychiatric hospital. There, he discovered that the patients received a scarily similar treatment to prisoners in jail.

By that time, Basaglia already had his own ideas about mental illness. He didn’t accept the idea that they had physical causes. He considered them a consequence of marginalization and dysfunctional environments.

This is a part of his first speech at the hospital: “A person with a mental illness goes into a mental hospital as a ‘person’. Once there, they become a ‘thing’. But patients are ‘people’ above all else and should be treated as such. We’re here to forget that we’re psychiatrists and remember that we’re people, just like them”.

His Experience in Trieste

In August of 1971, Franco Basaglia took over the management of a psychiatric hospital in Trieste, Italy with 1,182 patients. The community considered it a dump. They believed it was the perfect place for “bothersome” people that didn’t fit into society.

Basaglia started a transformation, both inside and outside the hospital. His ideas ended up gaining him the support of other psychiatrists, along with local governments and hospitals all over the world. They understood his theories and agreed with his idea that the psychiatric world needed a revolution.

As far as his work in hospitals, he thought it was vital to have artistic workshops with the patients. He also tried to create opportunities for them to create and follow up on their own projects and goals. The point was for them to stop being passive and for other people to stop thinking they had little or nothing to offer.

That was Basaglia’s basic goal: to prove that mentally ill patients were still able to do things, just in different ways.

A Hospital with Open Doors

The most important part of all was that he created an open-door system for the hospital. The patients could go outside, back into society. That also meant many of them were able to return home. On top of all that, Basaglia held meetings in the hospital to hear the patients’ opinions and try to find alternative solutions.

He wanted mental hospitals not to be considered marginal places within society. He also wanted the people of a community to help the patients re-integrate into that society.

His experiences led Franco Basaglia to start a movement to put an end to mental institutions and the ideas that they indirectly represented. That meant he had to fight against most of the psychiatric world of his day and age.

This world defended pushing patients to the outskirts and into controlled environments. It was the same world that simply believed those people would never be able to integrate into society.

Despite all that resistance, his ideas won in the end. He created the “democratic psychiatry” model and created the push for Italy to pass Law 180. The law placed a permanent ban on the forced confinement of people with a mental illness or dysfunction.

A True Psychiatric Revolution

By 1980, the Trieste hospital was completely transformed. All the old installations and procedures had been replaced with others that were cheaper, more humane, and more effective.

The mental institution made way for 40 different services. They no longer believed in confinement and seclusion. Their approach involved using new tools and resources such as home visits. They treated more acute cases of mental illness in apartments with small groups of people. This idea went on to become “psychosocial rehabilitation”.

Franco Basaglia died in 1980. He left behind ideas that forever changed the psychiatric landscape in many societies. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that his revolution did for psychiatry what Copernicus’ discovery that the Earth wasn’t the center of our solar system did for the world of science.

In a kind of contradictory way, what Basaglia was trying to tell us was that no one deserved to be rejected. He reminded people of the value of life, and, with that, of life’s meaning and purpose.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

Basaglia, F., & Ongaro, F. B. (1973). La mayoría marginada: la ideología del control social (Vol. 16). Laia.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.