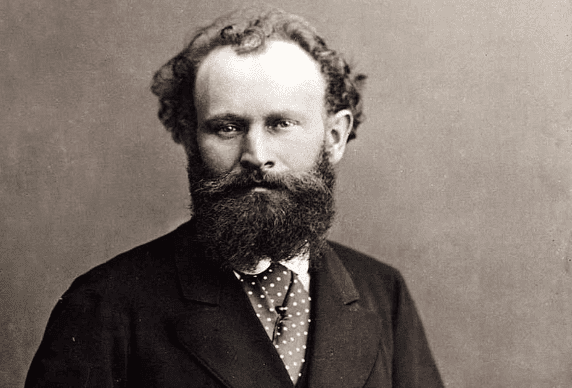

Édouard Manet: The First Impressionist

Édouard Manet was a 19th-century French painter who acted as inspiration for countless later painters, with his distinctive style and focus. Manet paved a new path by defying the traditional subjects in painting and portraying the events and circumstances of his time.

He exhibited his painting, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe in 1863. The critics tore him apart. But at the same time, he received praise and enthusiasm from a younger generation of painters who would go on to form the core of Impressionism.

Édouard Manet: The first impressionist

Early life

Édouard Manet was born on January 23rd, 1832, in Paris. His father, August Manet, was a high-ranking member of the Justice Ministry. His mother, Eugénie-Désirée Fournier, was the daughter of a diplomat and goddaughter to a Swedish prince in line to be king.

A wealthy family with many contacts, Manet’s parents hoped he would choose a respectable career, preferably as a lawyer. Little did they know that a much different path was in store for him.

In 1839, he studied at the Canon Poiloup school in Vaugirard. From 1844 to 1848, he was a boarding student at the Còllege Rollin. He wasn’t a good student. The only course that interested him was the one painting class they offered.

His father wanted him to enroll in law school, but Édouard decided not to go down that path. When his father refused to allow him to become a painter, he requested a place in the naval school, but didn’t pass the entrance exam.

At just sixteen years old, he set out as a navigation apprentice on a transport ship. When he came back to France in June, 1849, he failed his naval exam again. After this, his parents finally gave in to his stubborn insistence in becoming a painter.

Manet’s first formal studies

In 1850, Manet began studying with the classic painter Thomas Couture. It was with him that he developed an understanding of painting and its techniques.

In 1856, after six years with Couture, Manet set up a shared studio with Albert de Balleroy, an artist who did military paintings. It was here that he painted Boy With Cherries (1858). He was soon to move on to another studio, where he painted The Absinthe Drinker (1859).

In that same year, he made short trips to the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy. In between trips, he also spent time at the Louvre copying paintings by Tiziano and Diego Velázquez.

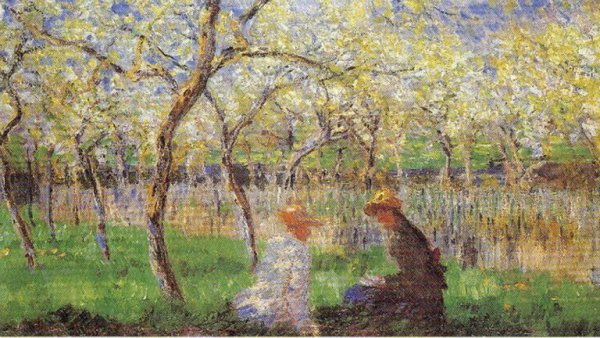

Despite his success with realism, Manet started to paint in a more relaxed, impressionistic style. One of the main characteristics was his use of broad strokes and a portrayal of common people doing daily tasks.

His canvases began to fill up with singers, people in streets, Roman people, and beggars. This unconventional subject matter, combined with a vast knowledge of the old masters, surprised some people and amazed many others.

Adult life and Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

Between 1862 and 1865, Édouard Manet took part in some expositions by the Galería Martinet. In 1863, he married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch woman who had given him piano lessons. They had already been together for ten years and had a child together before officially marrying.

That same year, the Salon jury rejected Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which he’d painted in a completely revolutionary style.

“I paint as I feel like painting; to hell with all their studies.”

-Édouard Manet-

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was inspired by works of old masters such as The Pastoral Concert (Giorgione, 1510) and The Judgment of Paris (Raphael, 1517-20). The painting caused a big stir and was the beginning of the “carnival notoriety” that plagued him throughout his career.

His critics felt offended at the notion that there was a naked woman in the company of two young men wearing contemporary clothes. Instead of seeming to them like a hazy allegoric figure, the woman’s modernity made her nudity strike them as vulgar and potentially threatening.

It also bothered the critics that Manet painted these people in a harsh, impersonal light. They also had trouble understanding why the people were in a forest environment that was clearly not realistic.

Major works

His painting, Olympia, which he did two years later, caused yet another scandal at the Salon in 1865. It shows a naked woman lying down and looking boldly at the viewer. He painted it with a harsh, bright light that almost erases the interior space, and turns her into a kind of two-dimensional figure.

This contemporary odalisque, which the French statesman Georges Clemenceau went on to have installed in the Louvre in 1907, was determined to be indecent by both critics and the public.

Deeply affected by the reception, Manet left for Spain in August 1865. But his stay there was short, because he didn’t like the food, and because it frustrated him to have no knowledge of the language.

While he was in Madrid, he met Théodore Duret, who ended up becoming one of the main proponents of his work. In 1866, he also came into contact with the novelist Emile Zola, and they struck up a friendship. Zola went on to write a brilliant article in the French newspaper Figaro in 1867.

Zola pointed out that nearly every important artist started out by offending public sensibilities. This review impressed art critic Louis-Edmond Duranty, who also began to support Manet. Then, painters such as Cézanne, Gauguin, Degas, and Monet became supporters as well.

Later years

In 1874, Manet received an invitation to take part in the first exhibition by impressionist painters. Despite his support for the movement, he rejected the invitation, and all the ones they sent after the first.

Manet felt that he needed to stay focused on the Salon and his place in the art world. Like many of his paintings, Édouard Manet was a contradiction. He was both bourgeois and common, both conventional and radical.

“One must be of one’s time and paint what one sees.”

-Édouard Manet-

A year after the first impressionist painting exhibition, he was given the opportunity to do illustrations for the French edition of The Crow by Edgar Allen Poe. In 1881, the French government awarded him the Légion d’honneur (The Legion of Honor).

He died two years later in Paris, on April 30th, 1883. On top of his 420 paintings, he left behind a reputation that would forever define him as a bold, influential artist.

Legacy

When he debuted as a painter, Manet encountered a lot of critical resistance to his work. That didn’t go away at all, until nearly the end of his career.

His fame rose towards the end of the 19th century thanks to the success of his commemorative exhibition and the critical acceptance of the impressionists. But it wasn’t until the 20th century that art historians gave him his status as one of the most important painters of his era.

Manet’s rejection of traditional models and perspectives were a symbol of the break from academic painting in the 19th century. There’s absolutely no doubt that his work helped pave the way for the revolutionary work of the impressionists and post-impressionists.

He also had a major influence on a great deal of the art of the 19th and 20th century, simply because of his choice of subject. His focus on modern, urban themes, which he portrayed in a direct, almost distant way, set him even farther apart from the standards of the Salon.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Venturi, L., & Fabricant, L. (1960). Cuatro pasos hacia el arte moderno: Giorgione, Caravaggio, Manet, Cézanne. Nueva Visión.

- Álvarez Lopera, J. (1996). Revisión de un lugar común: Goya y Manet. Reales sitios, 33, (128). Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.