Children Become Parents When Their Parents Get Old

Today, most parents live to a very old age. But this involves a decline in health that demands our care, protection, affection, and attention.

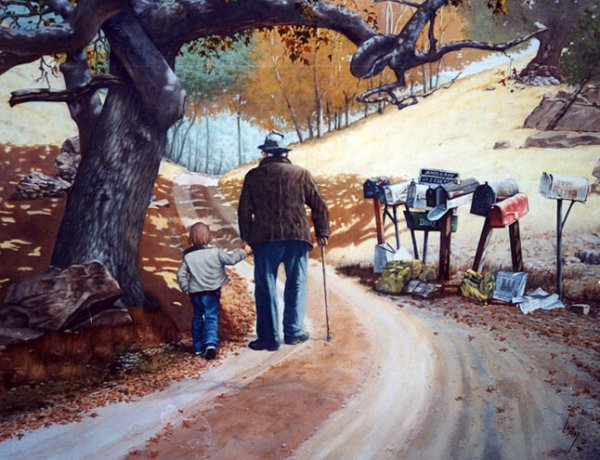

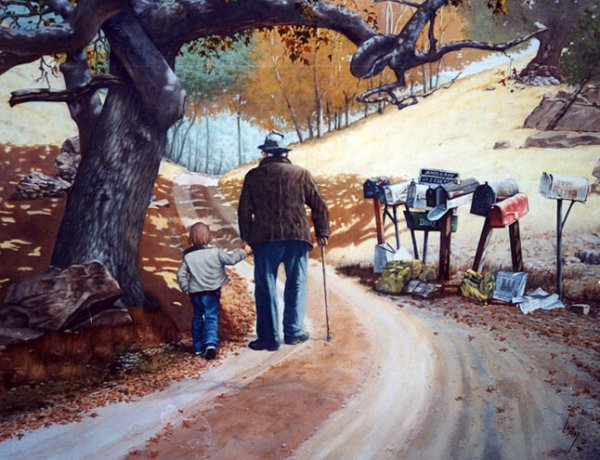

That’s why they say that we all become parents when our parents are near death. Because it’s our turn to hug them, feed them, and touch their souls with our words and care. We become walking sticks for their souls when we remind them, through our affection, of the warmth that they always brought to our lives.

It’s normal to look at old age and the last stage of life in a negative way. However, there are many reasons to think of it as a beautiful stage, and also one that’s essential for working through the grief.

Sharing that time with our parents or grandparents means sharing a need for affection that, in some way, also symbolizes the start of goodbye. It means supporting the people who made us grow and gave us life with the same force that it takes to say goodbye.

A message from an elderly parent:

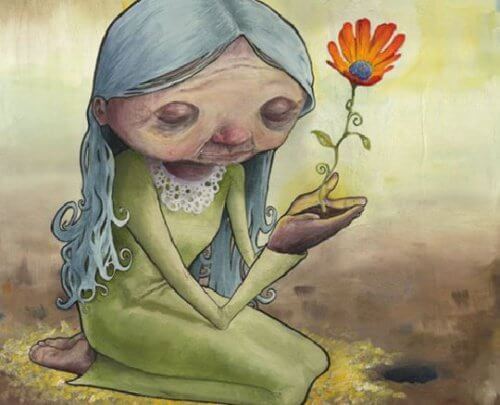

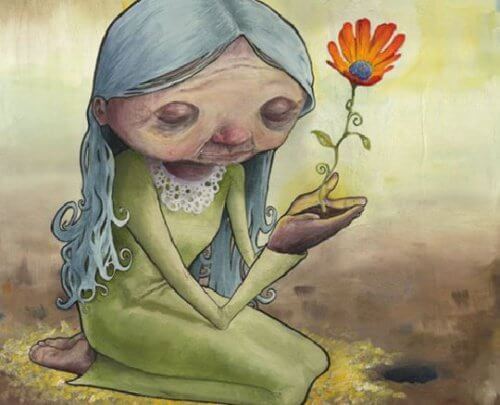

When I start to lose my memory or lose track of conversation, give me time to remember. When I can’t eat by myself, when I have accidents, or when I can’t even stand up, help me with patience.

Don’t despair because I’m older and have aches and pains. Don’t be embarrassed of me. Help me to get outside, breathe fresh air, and enjoy the light of the sun. Don’t lose patience because I walk slowly. Don’t get exasperated if I shout, cry, or bring up battles of the past.

Remember the time I spent teaching you to do what I need help with now, so that you could support me. I have a new mission in the family, so I’m asking you not to miss the opportunity I’ve given you. Love me when I get older, because I’m still me, even though my hair is gray.

The last goodbye to life

To reflect on the role of children when their parents get older, Fabricio Carpinejar wrote a wonderful piece that can offer us some light during a not-so-bright time. It’s usually pretty hard to feel okay because you can’t forget that you’re faced with saying goodbye to the person who taught you how to talk, grow, eat, and walk.

Here is what Carpinejar wrote:

“There’s a rupture in the history of the family, where ages accumulate and overlap, and the natural order of things doesn’t make sense: this is when the child becomes the parent of their parent.

It’s when the parent gets older and starts to walk like they’re moving through snow. Slow, slow, imprecise. It’s when the parent who held your hand with strength when you were little doesn’t want to be alone anymore. It’s when the parent, once strong and undefeatable, gets weaker and and has to catch their breath before getting up.

It’s when the parent, who once commanded and ordered you around, can now only breathe, grunt, and look for the door or the window, which now seem so far away to them. It’s when the parent, who was once prepared and hard-working, fails to put on their own clothing and can’t remember to take their medications.

And we, as children, can’t do anything but accept that we’re responsible for their life. The life that created us now depends on us to die peacefully.

Every child becomes a parent when their parent dies. Perhaps taking care of our elderly parents is strangely like pregnancy. It’s the final lesson. An opportunity to return the care and love that they gave us for decades.

And just like we prepare our houses to care for our babies by blocking electrical outlets and setting up playpens, now we rearrange the furniture to accommodate our parents. The first transformation occurs in the bathroom. As parents of our parents, we will install a bar in the shower.

The bar is emblematic. The bar is symbolic. Because bathing, which is normally simple and refreshing, has become a storm to the old feet of our protectors. We can’t leave them alone for one moment. The house will have clamps on the walls. And our arms will extend like a railing.

Getting old is walking while holding onto objects, getting old is even climbing a staircase without stairs. We’ll be strangers in our own homes.

We’ll observe every detail with fear and uncertainty, with doubt and worry. We’ll be frustrated architects, designers, and engineers. How did we not anticipate that our parents would get ill and need us? We’ll regret the couches, the statues, and the spiral staircase. We’ll regret all the obstacles and even the carpet.

Happy is the child who is a parent to their parent before they die! And unfortunate is the child who only shows up at the funeral and doesn’t get to say goodbye a little each day.

My friend Joe was with his father until his last minutes. In the hospital, the nurse went to move him from the bed to the stretcher in an attempt to change the sheets, when Joe called from his seat, ‘Let me help you.’

They combined their strength and he took his father in his lap for the first time. He put his father’s face on his chest. On his shoulders, he settled his father, shriveled by cancer, small, wrinkled, fragile, shaky.

He stayed there hugging him for quite some time, as long as his childhood, his adolescence, a long time, and endless amount of time. Rocking his father back and forth. Caressing his father, calming his father. And he whispered, ‘I’m here. I’m here, dad.’ What a father wants to hear at the end of his life is for his son to say he’s there.”

Although caring for our parents can be exhausting, we can’t forget that this sadness and tiredness is part of the grief that we have to work through. It’s part of the goodbye to that part of our soul, to our childhood.

With them, we lose all those things that we never shared with anyone else, that nobody else witnessed. This requires great deal of personal growth that life gives us the opportunity to carry out. We can’t pass it up.

Today, most parents live to a very old age. But this involves a decline in health that demands our care, protection, affection, and attention.

That’s why they say that we all become parents when our parents are near death. Because it’s our turn to hug them, feed them, and touch their souls with our words and care. We become walking sticks for their souls when we remind them, through our affection, of the warmth that they always brought to our lives.

It’s normal to look at old age and the last stage of life in a negative way. However, there are many reasons to think of it as a beautiful stage, and also one that’s essential for working through the grief.

Sharing that time with our parents or grandparents means sharing a need for affection that, in some way, also symbolizes the start of goodbye. It means supporting the people who made us grow and gave us life with the same force that it takes to say goodbye.

A message from an elderly parent:

When I start to lose my memory or lose track of conversation, give me time to remember. When I can’t eat by myself, when I have accidents, or when I can’t even stand up, help me with patience.

Don’t despair because I’m older and have aches and pains. Don’t be embarrassed of me. Help me to get outside, breathe fresh air, and enjoy the light of the sun. Don’t lose patience because I walk slowly. Don’t get exasperated if I shout, cry, or bring up battles of the past.

Remember the time I spent teaching you to do what I need help with now, so that you could support me. I have a new mission in the family, so I’m asking you not to miss the opportunity I’ve given you. Love me when I get older, because I’m still me, even though my hair is gray.

The last goodbye to life

To reflect on the role of children when their parents get older, Fabricio Carpinejar wrote a wonderful piece that can offer us some light during a not-so-bright time. It’s usually pretty hard to feel okay because you can’t forget that you’re faced with saying goodbye to the person who taught you how to talk, grow, eat, and walk.

Here is what Carpinejar wrote:

“There’s a rupture in the history of the family, where ages accumulate and overlap, and the natural order of things doesn’t make sense: this is when the child becomes the parent of their parent.

It’s when the parent gets older and starts to walk like they’re moving through snow. Slow, slow, imprecise. It’s when the parent who held your hand with strength when you were little doesn’t want to be alone anymore. It’s when the parent, once strong and undefeatable, gets weaker and and has to catch their breath before getting up.

It’s when the parent, who once commanded and ordered you around, can now only breathe, grunt, and look for the door or the window, which now seem so far away to them. It’s when the parent, who was once prepared and hard-working, fails to put on their own clothing and can’t remember to take their medications.

And we, as children, can’t do anything but accept that we’re responsible for their life. The life that created us now depends on us to die peacefully.

Every child becomes a parent when their parent dies. Perhaps taking care of our elderly parents is strangely like pregnancy. It’s the final lesson. An opportunity to return the care and love that they gave us for decades.

And just like we prepare our houses to care for our babies by blocking electrical outlets and setting up playpens, now we rearrange the furniture to accommodate our parents. The first transformation occurs in the bathroom. As parents of our parents, we will install a bar in the shower.

The bar is emblematic. The bar is symbolic. Because bathing, which is normally simple and refreshing, has become a storm to the old feet of our protectors. We can’t leave them alone for one moment. The house will have clamps on the walls. And our arms will extend like a railing.

Getting old is walking while holding onto objects, getting old is even climbing a staircase without stairs. We’ll be strangers in our own homes.

We’ll observe every detail with fear and uncertainty, with doubt and worry. We’ll be frustrated architects, designers, and engineers. How did we not anticipate that our parents would get ill and need us? We’ll regret the couches, the statues, and the spiral staircase. We’ll regret all the obstacles and even the carpet.

Happy is the child who is a parent to their parent before they die! And unfortunate is the child who only shows up at the funeral and doesn’t get to say goodbye a little each day.

My friend Joe was with his father until his last minutes. In the hospital, the nurse went to move him from the bed to the stretcher in an attempt to change the sheets, when Joe called from his seat, ‘Let me help you.’

They combined their strength and he took his father in his lap for the first time. He put his father’s face on his chest. On his shoulders, he settled his father, shriveled by cancer, small, wrinkled, fragile, shaky.

He stayed there hugging him for quite some time, as long as his childhood, his adolescence, a long time, and endless amount of time. Rocking his father back and forth. Caressing his father, calming his father. And he whispered, ‘I’m here. I’m here, dad.’ What a father wants to hear at the end of his life is for his son to say he’s there.”

Although caring for our parents can be exhausting, we can’t forget that this sadness and tiredness is part of the grief that we have to work through. It’s part of the goodbye to that part of our soul, to our childhood.

With them, we lose all those things that we never shared with anyone else, that nobody else witnessed. This requires great deal of personal growth that life gives us the opportunity to carry out. We can’t pass it up.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.