The I Ching: More Than Just an Oracle

The I Ching, which has been preserved in China, is one of the oldest books known to man. It’s thought to have been written around 1200 years ago and is of Taoist origin. Its name in English means “Book of Changes”. In the West, it became popular as an oracle. However, rather than a divinatory text, it’s more of a moral guide and a philosophical and cosmogonic discourse. Indeed, its function isn’t so much to predict but rather to impart certain principles to you, the reader, you then reflect on. You then work out an answer to your question on the basis of your own intuition.

“The future is as irreversible

As ironclad yesterday. There’s no matter

Unless it be a dark and soundless letter

Of the eternal Writ no tongue can tell,

Whose book is time.”-Jorge Luis Borges, Poem for Richard Wilhelm’s version of the I Ching-

What we know today as the I Ching isn’t the original. In fact, it’s undergone several transformations over time. Texts have been deleted and added, both to enrich it and make it more understandable.

What’s the I Ching?

The I Ching was initially developed with the idea that the only constant thing in the world and life is change. It’s also based on the principle that everything you do can lead to changes in the universe. Also included in this principle is what you don’t do.

It raises the opposite principle as well. In other words, that nothing you do or stop doing can change the fundamental course of the universe. You sometimes might be able to modify things. However, you can never fundamentally change them.

The I Ching or Book of Changes mainly aims to reflect on who you are, how you feel, and how you can act in order to harmonize with the universe. It does this by imparting specific messages to you. These are encrypted to a certain extent, and you have to interpret them for yourself. Your interpretation then leads you to follow a particular course of action.

Ambiguity and uncertainty

The I Ching isn’t strictly a book of divination because it doesn’t suggest that your destiny’s already been written. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Because you only consult the I Ching when you want to know what to do in certain circumstances. This means that it’s ultimately you that makes the final decision, based on the I Ching.

The answers that the I Ching gives aren’t definitive. For example, you can’t say, “I’ve been working so hard in the garden. Will I win the best garden competition now?” You won’t find an answer to a question like this in the text. That’s because the I Ching will always answer in uncertain terms.

Some explain this ambiguity with examples like this. If a couple has an adopted child, do they have children or don’t they? In fact, the deepest and most valuable questions don’t have categorical answers. This is what the I Ching emphasizes.

Therefore, in order to consult the I Ching, you not only have to learn to interpret its answers, but you also have to ask the right questions. Otherwise, you won’t gain any benefit.

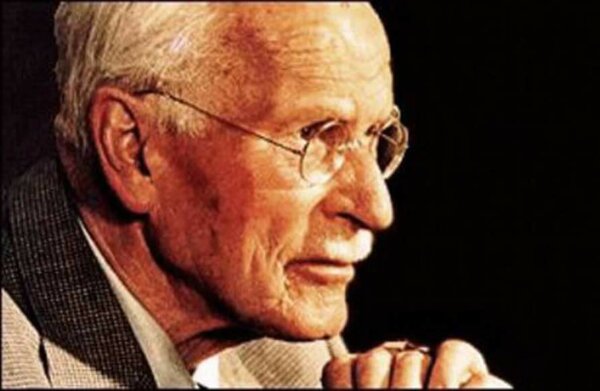

Carl Jung and the I Ching

Carl Gustav Jung frequently used the I Ching. He saw it as a means to access the contents of the unconscious. This was particularly valid within the framework of his psychoanalysis. In fact, Jung wrote the prologue to the most classic translation of the I Ching, written by Richard Wilhelm.

For many theorists, Jung’s concept of “synchronicity” relates closely to his experiences with the I Ching. According to this concept, nothing that happens is ever due to chance. The theory suggests that invisible lines connect some events with others. This results in the reality you’re subsequently presented with.

For Carl Jung, one of the ways to gain access to the understanding of his synchronicity was the I Ching. This book lets you know how but not what. It lets you know what for but not why. Indeed, when you consult it properly, you start to connect things in your life that might have previously seemed unrelated and you begin to make sense of them.

You can’t read the I Ching as an ordinary book. That’s because it’s designed as an oracle. Furthermore, you can read it a thousand times and each time it’ll probably seem like a different book. However, if you use it properly, you’ll find it an important source of enlightenment.

The I Ching, which has been preserved in China, is one of the oldest books known to man. It’s thought to have been written around 1200 years ago and is of Taoist origin. Its name in English means “Book of Changes”. In the West, it became popular as an oracle. However, rather than a divinatory text, it’s more of a moral guide and a philosophical and cosmogonic discourse. Indeed, its function isn’t so much to predict but rather to impart certain principles to you, the reader, you then reflect on. You then work out an answer to your question on the basis of your own intuition.

“The future is as irreversible

As ironclad yesterday. There’s no matter

Unless it be a dark and soundless letter

Of the eternal Writ no tongue can tell,

Whose book is time.”-Jorge Luis Borges, Poem for Richard Wilhelm’s version of the I Ching-

What we know today as the I Ching isn’t the original. In fact, it’s undergone several transformations over time. Texts have been deleted and added, both to enrich it and make it more understandable.

What’s the I Ching?

The I Ching was initially developed with the idea that the only constant thing in the world and life is change. It’s also based on the principle that everything you do can lead to changes in the universe. Also included in this principle is what you don’t do.

It raises the opposite principle as well. In other words, that nothing you do or stop doing can change the fundamental course of the universe. You sometimes might be able to modify things. However, you can never fundamentally change them.

The I Ching or Book of Changes mainly aims to reflect on who you are, how you feel, and how you can act in order to harmonize with the universe. It does this by imparting specific messages to you. These are encrypted to a certain extent, and you have to interpret them for yourself. Your interpretation then leads you to follow a particular course of action.

Ambiguity and uncertainty

The I Ching isn’t strictly a book of divination because it doesn’t suggest that your destiny’s already been written. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Because you only consult the I Ching when you want to know what to do in certain circumstances. This means that it’s ultimately you that makes the final decision, based on the I Ching.

The answers that the I Ching gives aren’t definitive. For example, you can’t say, “I’ve been working so hard in the garden. Will I win the best garden competition now?” You won’t find an answer to a question like this in the text. That’s because the I Ching will always answer in uncertain terms.

Some explain this ambiguity with examples like this. If a couple has an adopted child, do they have children or don’t they? In fact, the deepest and most valuable questions don’t have categorical answers. This is what the I Ching emphasizes.

Therefore, in order to consult the I Ching, you not only have to learn to interpret its answers, but you also have to ask the right questions. Otherwise, you won’t gain any benefit.

Carl Jung and the I Ching

Carl Gustav Jung frequently used the I Ching. He saw it as a means to access the contents of the unconscious. This was particularly valid within the framework of his psychoanalysis. In fact, Jung wrote the prologue to the most classic translation of the I Ching, written by Richard Wilhelm.

For many theorists, Jung’s concept of “synchronicity” relates closely to his experiences with the I Ching. According to this concept, nothing that happens is ever due to chance. The theory suggests that invisible lines connect some events with others. This results in the reality you’re subsequently presented with.

For Carl Jung, one of the ways to gain access to the understanding of his synchronicity was the I Ching. This book lets you know how but not what. It lets you know what for but not why. Indeed, when you consult it properly, you start to connect things in your life that might have previously seemed unrelated and you begin to make sense of them.

You can’t read the I Ching as an ordinary book. That’s because it’s designed as an oracle. Furthermore, you can read it a thousand times and each time it’ll probably seem like a different book. However, if you use it properly, you’ll find it an important source of enlightenment.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Cleary, T. (2005). I Ching/I Ching: El libro del cambio/The Book of Change. Edaf.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.