Freud's Pleasure Principle: Pleasure in Displeasure?

Written and verified by the psychologist Martina Estevan Del Carpio

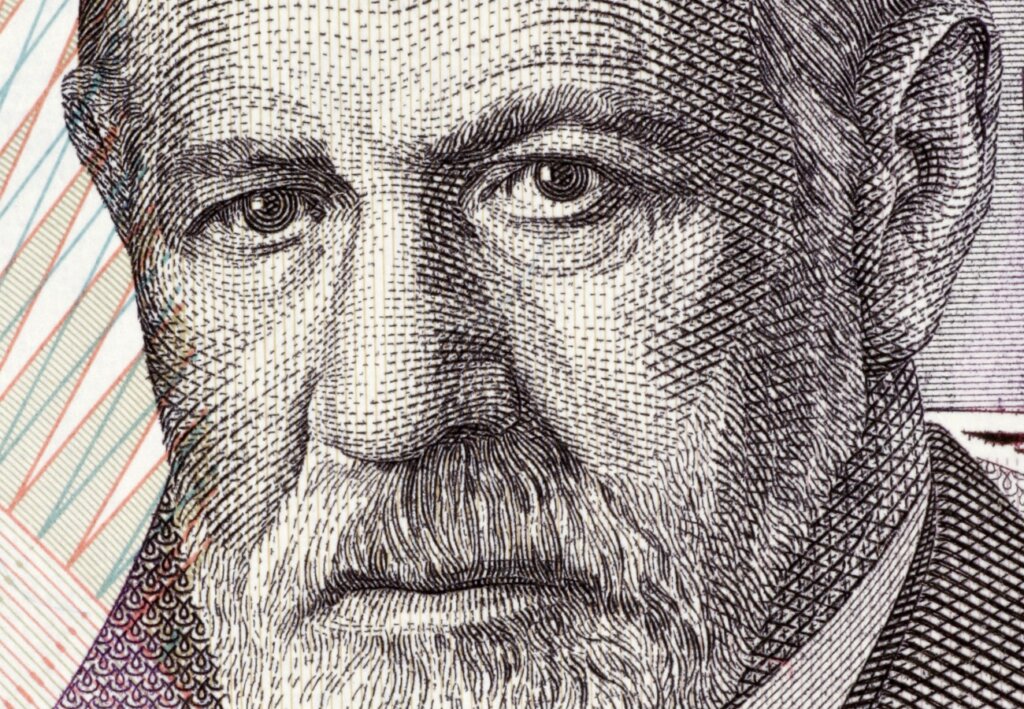

If you’re not interested in breaking with the common canons of thought, it might be better that you stop reading now. On the other hand, if you’re keen to do so, we’re going to explore what Sigmund Freud was referring to in his essay, Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

One of the motivations that guided the work of this father of psychoanalysis was his desire to know more about the constitution of the psychic apparatus. In other words, how our psyche works. In his first theories, he came to the conclusion that the structure of the psyche bases its dynamism on the pleasure principle.

Freud’s constitution of the psychic apparatus

For Freud, the psyche was constituted by three psychic instances:

- The unconscious.

- The conscious.

- The preconscious.

Separate systems, different operations

Freud believed that, in the unconscious, there are a series of psychic elements of deep origin. In effect, they’re a set of traumas that have been repressed, hidden, and buried. These memories represent a conflict for the subject.

On the other hand, he saw the conscious as the recognized and accepted region, from where the individual interacts with the outside world and the people that surround them.

Finally, in the preconscious, Freud saw contents that either become conscious representations or sink into the depths of the unconscious.

These three systems gave shape to the psychic apparatus. In order to sustain itself, it requires the assistance of a mediating function or censorship. In fact, a function without which the repressed contents would find no opposition to gaining access to consciousness.

Freud claimed that censorship is a function that’s essential and permanent. It constitutes a kind of selective barrier that prevents the free flow of information between the unconscious systems, on the one hand, and the preconscious-conscious systems, on the other. It prevents unconscious desires and the formations derived from them from accessing the plane of consciousness. Thus, they’re located at the origin of repression.

As we mentioned earlier, in the first instance, the functioning of the psychic apparatus is sustained in the pleasure principle.

The pleasure principle, Freud’s first theory

These three systems come into conflict when a voltage invades the device. Freud stated that tension is an energetic charge that occurs and generates a disturbance in the functioning of the psyche. It disrupts the feeling of pleasure, as it’s momentarily lost.

Faced with this irruption, the device responds in a manner approaching pleasure. In other words, it tries to discharge its energy and resume its lost pleasure. Freud identified this force or impulse that guides the discharge as drive.

If we now return to our first question, we can account for something beyond the pleasure principle.

Beyond the pleasure principle

The metapsychological change from the first to the second topic was initially driven by some findings from the psychoanalytic field.

In 1920, Sigmund Freud made a 180 turn in his theory. In effect, he acknowledged his own failings and developed a new topic on this functioning. He began to distinguish between two types of drives:

- Life or erotic drive. It fights for pleasure, love, and sexual desire.

- The death drive. It’s directed to the most unpleasant of places. For instance, sadomasochism and aggressive and destructive tendencies.

Given these diverse characteristics and manifestations, it’s clear that there are two unethical drives. That said, they turn out to be two sides of the same coin.

Indeed, both drives pursue the same realization or satisfaction of a goal. Freud believed that there can be erotic feelings charged with aggressiveness or forms of violence saturated with sensuality. The ultimate purpose of both drives refers to the satisfaction of unconscious desire.

Superego, Id, and I

Freud no longer spoke of the three instances mentioned above, but of the superego, id, and I.

- The Id. This concept was adopted by the field of psychoanalysis to designate the drive pole of the subject. It’s the basic instinct, the most ancient, elemental, and archaic part of our psychic apparatus.

In the id, we see our most primitive drives acting. They govern, without restriction, the principle of pleasure. This drives the direct and immediate discharge of tensions and accumulated excitement and converging processes. For example, condensation and displacement. They bear the unmistakable stamp of the unconscious. Moreover, they contain the basic and spontaneous drives of sexuality and aggressiveness.

- The I. This is the psychic apparatus that embodies the world of reason and reflection. It tries to transmit to the id the influence of the external world. Furthermore, it aspires to replace the pleasure principle, which reigns without restrictions in this instance, with the principle of pleasure and reality.

The I must mediate and achieve consensus between the three demands of the id which seeks its direct and immediate satisfaction. However, the requirements of reality sometimes make it impossible or dangerous to satisfy some of these drives. Moreover, the coercive imperatives of the moral conscience, far from seeking a sensible economy of pleasure, tend to develop feelings of guilt and the quality of obligation.

The superego

- The superego or ideal of the I. This is a global structure that has three important functions. These are self-observation, moral conscience, and the formation of ideals.

The superego is constituted by the uncritical internalization of moral, social, and cultural norms and values. In effect, internalization takes place through successive identifications with the idealized figures of the parents. The subject assimilates a trait, quality, or attribute of another individual and transforms themselves, either totally or partially, on this model.

Therefore, if an individual wishes to vindicate the destinies of their existence, they must be able to achieve a compromise between the need to adapt to reality, the need to respond to the drive demands of the Id fed by its own archaic heritage, and its prescriptions and cultural ideals. They try to impose themselves on the individual from the requirements of the superego.

The path of desire as a motor

Desire, as unconscious, is never purely erotic. Moreover, desire can’t be named, it can’t be reached, nor does it appear to us in clear and easy-to-interpret forms. Desire moves us, life motorizes us.

Have you ever experienced desire? It’s indecipherable, it carries with it the sense of a certain lacking. When you think you have it, it slips away again. For instance, when you find yourself thinking “I thought I wanted that, but now that I have it, I want more. I want something else. I no longer want the same as before”.

This is how the pleasure principle works. In effect, paradoxically, by not working. It means that whenever you’re moving forward, you recognize that you’re not the only owner of your ideas. In fact, as crazy as it may seem, you’re not guided by the pleasure of being here.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Ansermet, F., & Magistretti, P. (2011). Los enigmas del placer. Katz Editores.

- Colín, A. (2015). De la pulsión de muerte, el deseo, y la pulsión invocante. Revista Fuentes Humanísticas, 27(51), 25-40.

- Freud, S. (2020). Más allá del principio del placer (Vol. 357). Ediciones Akal.

- Laznik, D., Lubián, E., & Kligmann, L. (2011). La segunda tópica freudiana: sus dimensiones clínicas. Anuario de investigaciones, 18, 81-85.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.