Averroes and 17 Other Philosophers from the Middle Ages

Written and verified by the philosopher Matias Rizzuto

Despite the perception of the Middle Ages as a dark period, it was actually an era rich in nascent reflections by prominent philosophers. From the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the beginning of the Renaissance, intellectuals across Europe strove to fuse the teachings of Christianity with classical philosophy, giving life to debates and new schools of thought.

Influenced by Greek, Roman, Islamic, and Jewish traditions, medieval sages addressed existence, morality, and man’s relationship with God. Their contributions, which are still relevant today, have significantly shaped the landscape of Western thought. Keep reading to get to know more about them!

Notable philosophers from the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages bequeathed important reflections, knowledge, and models of thought through the philosophers who lived at that time. Below, find out who they are.

1. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD)

Known as Saint Augustine, he was an influential figure in Western Christianity. Born in Tagaste (present-day Souk Ahras, Algeria), Augustine lived a tumultuous youth. There, he immersed himself in various philosophical and spiritual currents, with special emphasis on Manichaeism and Neoplatonism.

His book Confessions (398) recounts his spiritual search and eventual conversion to Christianity, all through a journey of unprecedented intellectual restlessness.

This book isn’t only considered one of the great works of Christian literature but is also a source of inspiration for philosophers and authors throughout the centuries due to its candid examination of human nature and the relationship of the individual with God.

2. Boethius (480-524 AD)

Boethius was a Roman philosopher and politician whose efforts to harmonize the philosophical thought of classical antiquity with Christian teachings left a lasting impact on the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Throughout his life, Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius distinguished himself as a scholar committed to translating and commenting on the works of Aristotle and Plato into Latin. Because of this, his writings were essential for the preservation of Hellenistic thought.

However, it’s thanks to his work entitled The Consolation of Philosophy (524) that his name endures to this day. Written during his imprisonment shortly before his execution, this philosophical dialogue between Boethius and the personification of philosophy addresses reflections on the ephemeral nature of earthly fortune and the search for true and eternal good.

3. Juan Scotus Erigena (810-877 AD)

Erigena was an Irish-born Neoplatonic theologian and philosopher who played a crucial role in the transition from ancient to medieval thought. He stood out as a bridge between the philosophical traditions of the Greek world and the emerging theological traditions of medieval Europe.

His masterpiece, Periphyseon or De Divisione Naturae (867), is a dialogue that explores the relationship between God, nature, and humanity and addresses the question of how divinity manifests itself in creation.

Although his ideas were considered heterodox and eventually received condemnation from the Church, his influence on the discipline during the Middle Ages and on later philosophers, such as Meister Eckhart and Nicholas of Cusa, is undeniable.

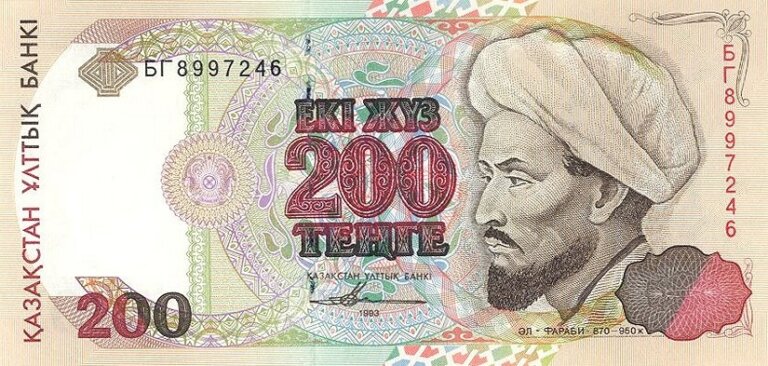

4. Al-Farabi (872-950 AD)

Known as “The Second Master” after Aristotle, he was one of the most prominent Islamic philosophers of the Middle Ages and a pioneer in the study of logic and political philosophy. Al-Farabi combined and synthesized elements of Greek, Persian, and Islamic philosophical traditions.

His contributions covered areas as diverse as music, mathematics, cosmology, and ethics, but it was his commentary on and reinterpretations of Aristotle’s works that gave him prestige.

In the field of political philosophy, his work Virtuous City or Al-Madina al-fadila stands out for its vision of an ideal society governed by a philosopher leader, in a vein similar to Plato’s Republic.

5. Avicenna (Ibn Sina) (980-1037 AD)

Avicenna was a Persian polymath who explored various fields of knowledge of his time, from medicine and philosophy to astronomy and alchemy. Many consider him the father of modern medicine, and his influence spread beyond the Islamic world, reaching medieval Europe.

His best-known work, The Canon of Medicine or Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb (1025), served as a primary reference in medicine for centuries.

In the realm of philosophy, Avicenna strove to merge and reconcile Aristotelian thought with the principles of Islam. And his Book of Healing or Kitab al-Shifa (1027) is a testament to this monumental effort.

The conception of the “necessary being,” a being that exists for itself and on which everything else depends, is a pillar of Avicenna’s metaphysics and had a significant influence on medieval and Renaissance thinking about the existence and nature of God.

6. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109)

Also known as Saint Anselm, he was an Italian Benedictine monk, theologian, and philosopher who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury. He’s known for his contributions to theology and philosophy, especially with regard to arguments about the existence of God.

His rationalist approach to faith and his emphasis on the ability of reason to approach the understanding of divine mysteries position him as a fundamental figure in the development of scholasticism, a philosophical and theological movement that sought to use reason and logic in the study of faith.

7. Peter Abelard (1079-1142)

Peter Abelard was a medieval philosopher, theologian, and logician of great relevance in the intellectual field of 12th-century Europe. This central figure at the University of Paris was known for his skill in dialectics, a form of debate that employs logic and argumentation.

Throughout his academic career, Peter Abelard didn’t hesitate to question and challenge traditional doctrines, which often led him into confrontations with other prominent thinkers and ecclesiastical authorities of his time.

His work Sic et Non (1141) is a clear example of his dialectical approach. In this writing, he presented contradictions in the writings of the Church fathers, encouraging critical analysis and a deeper theological debate.

8. Averroes (Ibn Rushd) (1126-1198)

Born in Córdoba, in Muslim Spain, Averroes went down in history for his extensive commentaries on the works of Aristotle. His meticulous interpretation of the Greek philosopher not only revitalized the study of Aristotle in the Islamic world but, after being translated into Latin, also laid the foundation for the Aristotelian revival in medieval Europe.

Averroes defended the idea that philosophy and religion were complementary and could coexist harmoniously. According to his writings, truth, whether reached through philosophical reason or religious revelation, remains a unified truth.

9. Maimonides (1135-1204)

Also known by his Hebrew name, Moisés ben Maimón, or by his acronym, Rambam, he was a Jewish scholar of Andalusian origin whose contributions to Judaism, philosophy, and medicine have left a lasting legacy over the centuries. Born in Córdoba during the heyday of Muslim Spain, Maimonides was both a prominent rabbi and a respected physician.

In his philosophical work Guide of the Perplexed (1190), he attempted to reconcile the teachings of Aristotelian philosophy with the principles of Judaism. He addressed complex questions, such as the nature of God, prophecy, and the problem of evil, attempting to provide rational answers to theological dilemmas.

Throughout his life, he faced criticism both from conservative Jewish sectors, who viewed his philosophical inclinations with suspicion, and from Muslim thinkers.

10. Albertus Magnus (1200-1280)

Albertus Magnus was one of the first to introduce and comment extensively on the works of Aristotle in Europe. At a time when many of the Greek philosopher’s works were unknown or viewed with suspicion, Saint Albert the Great advocated for the integration of Aristotelian thought with Christian theology. For Albertus, philosophy and religion, far from being opposites, could enrich each other.

In addition to his deep interest in philosophy, Albertus was a pioneer in the empirical study of nature. His research in fields as varied as botany, zoology, chemistry, and geology reflected an observational and experimental approach, anticipating some aspects of the modern scientific method.

11. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

This thinker is undoubtedly one of the most transcendent in the history of philosophy and theology. In a period when the rediscovery of Aristotle’s works in Western Europe generated tensions and debates in academia, Thomas Aquinas defended the idea that reason and faith are complementary and that knowledge of God could be achieved through rational means.

His best-known work, the Summa Theologica (1274), is a theological compendium in which he addresses and analyzes almost all the fundamental topics of theology and philosophy, from the existence and nature of God to ethics and the nature of good and evil. Aquinas raises objections, responses, and then refutations to each topic with deep erudition and argumentative skill.

12. Roger Bacon (1214-1294)

Roger Bacon was an English philosopher and Franciscan friar recognized for his early emphasis on the empirical method in research and his advocacy of the role of experimentation in the advancement of knowledge. At a time when the authority of ancient texts and tradition often trumped direct observation, Roger Bacon advocated a more systematic and practical approach.

He also highlighted the relevance of mathematics in understanding the universe and defended the idea that knowledge should be sought not only for theological or philosophical reasons but also to improve the human condition.

In addition to his methodological contributions, Bacon wrote on optics, alchemy, and astronomy and predicted future inventions, such as eyeglasses and self-propelled vehicles.

13. John Duns Scotus (1266-1308)

John Duns Scotus taught at the universities of Oxford and Paris. His contributions to theology and philosophy established him as a central figure of late scholasticism. His ability to address and resolve theological problems with subtle and sophisticated arguments earned him prestige in his time.

One of Scotus’s most notable contributions was his defense of the concept of “free will” in the context of theology. He argued that God’s will is absolutely free and is not determined by any logical necessity. With this, he underlined the primacy of will over intellect. This position differed from that of other thinkers of his time, such as Thomas Aquinas.

14. Meister Eckhart (1260-1328)

Meister Eckhart was a German theologian, philosopher, and mystic associated with the Order of Preachers or Dominicans. His thought combines elements of scholastic theology with deep mystical insights. His sermons and treatises exploring the intimate relationship between the human soul and God establish him as one of the most important philosophers of the Middle Ages.

At the center of his teaching is the idea of the “spark of the soul,” an immanent point in the soul where the divine presence is found and the individual can unite directly with God. His work stands out for its emphasis on disappropriation, the process by which the soul strips itself of all images, concepts, and desires in order to encounter the divine.

Eckhart advocated an experiential relationship with God that went beyond rituals and mediations. His ideas, especially those referring to the nature of union with God and divine transcendence, were condemned by the Church as heterodox.

15. William of Ockham (1287-1347)

A member of the Franciscan Order, Ockham is frequently associated with the school of thought known as nominalism. This rejects the existence of universals (abstract concepts or shared qualities) outside of individual and concrete things. He maintained that only individuals exist and that universals are names or labels that we put on things.

In addition to his contributions to nominalism, Ockham is famous for the epistemological principle that bears his name: Ockham’s razor. This philosophical tool maintains that, in the face of multiple hypotheses that explain the same phenomenon, the simplest explanation should be preferred; that is, the one that proposes the smallest number of entities or assumptions.

16. Ramon Llull (1232-1315)

Ramon Llull’s attempt to create an art or logical-combinatorial method to demonstrate and disseminate the truths of Christianity earned him a place among the most important philosophers of the Middle Ages.

His system, called ars magna, used a series of rotating geometric figures that represented theological and philosophical concepts, seeking to generate combinations of arguments to address any theological or philosophical question.

Although his combinatorial method was not frequently used or adopted by the intellectuals of his time, that doesn’t mean that it had no impact. Many don’t hesitate to consider Llull’s system to be the pioneer of computational logic. So, his ideas served as an inspiration to many later thinkers.

17. Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464)

Nicholas of Cusa was a theologian, philosopher, mathematician, and cardinal of the Catholic Church whose thought represented a significant transition between medieval philosophy and emerging Renaissance ideas.

His most influential work, De Docta Ignorantia (1440), explores the idea that human knowledge, no matter how vast, is always limited compared to the infinitude of God. Therefore, true wisdom lies in recognizing our own ignorance.

Nicholas of Cusa introduced the concept of coincidentia oppositorum (the coincidence of opposites), which maintains that the deepest truths are often found in the union of seemingly contradictory ideas. In addition, he made important contributions to the field of mathematics, particularly in regard to the concept of infinity.

18. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494)

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola was an Italian Renaissance philosopher and humanist whose ideas encapsulated the spirit of the Renaissance in his quest to harmonize diverse traditions of thought and emphasize the potential and dignity of the human being.

From an early age, he displayed an insatiable thirst for knowledge, and his education encompassed a wide variety of disciplines, from classical philosophy to Jewish theology and Sufi mysticism. He’s best known for his work Oration on the Dignity of Man (1496), a text that has often been described as “the Manifesto of the Renaissance.”

In this treatise, Pico argues that humans occupy a unique position in the hierarchy of the cosmos, for, unlike other creatures who have a fixed place, humans have the freedom and choice to ascend to the heights of the divine or descend to the depths of the bestial.

Importance and significance of medieval philosophers

The above list is useful to understand the importance of philosophers of the Middle Ages in the construction of modern thought.

Contrary to popular opinion, the Middle Ages was a period of extensive philosophical development, so much so that many of its theorems remained in force for centuries. Modern philosophy and contemporary philosophy can’t be understood without the contributions of medieval thinkers.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Hirschberger, J., & Gómez, L. M. (2011). Historia de la filosofía: Antigüedad, edad media, Renacimiento. Tomo I. Herder.

- Marenbon, J. (14 de septiembre de 2022). Medieval Philosophy. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/medieval-philosophy/

- Maurer, A. (19 de mayo de 2023). Medieval philosophy. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/medieval-philosophy

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.