Mist, a Renaissance "Nivola" by Unamuno

In 1914, Miguel de Unamuno published a rather peculiar novel, one that he preferred to classify as Nivola, thus avoiding the criticism that would arise if people compared it with other works. The name of the novel is Niebla in Spanish and it was translated to English as Mist. Today’s article will explore this literary jewel.

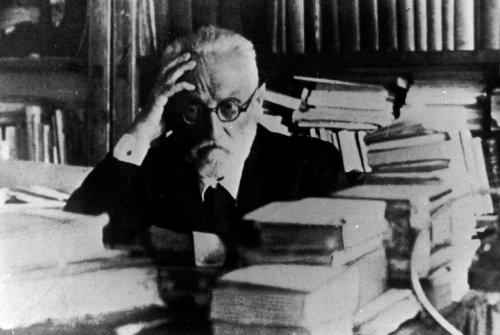

Unamuno is one of the most important authors of Spanish literature. He was born in Bilbao in 1864 and died in Salamanca in 1936. Today, his name resonates as one of the greatest novelists and he’s also one of the representatives of the Generation of 1898.

Through this work, Miguel gathers many of the ideas he presented in his previous writings. However, he does so through the life of Augusto Pérez, his main character, whom he portrays as a wealthy man with a law degree. The story itself doesn’t have too many twists, but the writer did try to give it another dimension.

A new work that he himself would list under the category of “Nivola” and not a novel, as people would conventionally describe it otherwise. Today’s article will reveal some of the keys to this book.

The “Nivola” argument

Something that’ll catch the reader’s attention early on is that the prologue is signed by Víctor Goti. He’s one of the characters in the play. Also, the author makes a post-prologue in which he states that the reader isn’t about to read a novel, but a “Nivola“.

To further confuse everyone, the epilogue narrates the events of the play. But it does so from the point of view of Orpheus, the dog of the aforementioned Augusto Pérez.

It all begins when Augusto sees a woman he ends up falling madly in love with. He’ll try to get her attention with his limited resources, but she’ll reject him because she’s already with someone else. However, she’ll eventually agree to meet, but only to take advantage of him. Finally, she writes to him on her wedding day explaining it was all a hoax.

From this moment on, the reader witnesses an authentic revolution from a narrative point of view. Augusto is so unhappy that he plans to commit suicide. However, he’s merely the character in a play and, as such, lacks free will. Only Unamuno, the author, can make the final decision.

and then …

At this moment, what some know as the “fourth wall” breaks. Thus, Augusto decides to talk to the author. Thus, he speaks directly to Unamuno.

The character ends up rebelling against the author, exposing his intentions. This way, the author begins to wonder if he himself is a character from another fictional story. To what extent does he have free will? The goal is that, when Unamuno begins to doubt his own freedom and reality, the reader will also question their own existence at the exact same moment. Therefore, what if humans only exist in a dream? What if they’re only part of someone’s dream?

The magnitude of the novel isn’t only present in the plot, but in its capacity for dialogue with the reality of the reader and the author. Hence, Unamuno decides that the work should be a part of another genre classification. In a separate category riddled with paratexts. Also, by calling it Nivola, he blocks the sort of criticism that could label or compare it.

Realities and fictions in Mist, a “Nivola” by Unamuno

Unamuno’s work bears some resemblance to Life Is a Dream by Pedro Calderón de la Barca. In some ways, fiction is more real than the authors themselves and, for Unamuno, the characters have a life of their own. Thus, the reader makes them live and what matters is how one revives literature.

All this is closely related to the problem of immortality. That is, if you’re what you dream of and everyone’s dream is just common reality, there’s no way to tell that it’s real.

Unamuno read the works of Descartes and Calderón de la Barca. In fact, that’s precisely where he got the inspiration for his Nivola. There’s a reflection of Descartes’ rationalism, because, in principle, there’s no reason to believe that what surrounds humans is more than a dream.

Unamuno, despite being a believer, can’t rationally deduce the existence of God as Descartes does. Therefore, he has no reason to believe that what surrounds him is a dream or a deception. So, how would you know when your senses are deceiving you?

Unamuno gathers all this complexity in Mist, drawing from different regions. For one, fiction, where the characters live. Then, there’s framing fiction, the place of the reality of fiction which is the place where the fictitious author lives. Finally, outside the book, in the limits, there’s another reality: the reality of the reader.

With Mist, the author describes various planes that intertwine. The author ends up taking the role of a character when he meets Augusto. In other words, the reader is before a reality of reality that’s the world around them and, in turn, a reality of fiction where Unamuno is. In the end, the characters are in the fiction of fiction.

More philosophical aspects of Mist in the Nivola by Unamuno

As you may anticipate, another of Mist‘s fundamental questions is about free will. It’s posed from two perspectives: the first is found in the fictional entity, from which the character arises if they’re free.

There’s Augusto who wants to commit suicide but finds that Unamuno won’t allow it so he can’t go through with it because he’s simply a character. At this point, the same doubt appears in the mind of the reader.

The characters are born from a language, from an inheritance. It’s for this reason that you’re not free to think what you think and the two possibilities arise again: God doesn’t exist, and reality is nothing more than the dream that people dream. Or that God does exist and humans are just a divine dream.

Augusto fights for his life. It may be fictional, but it’s his, after all. In his despair, the character of Augusto announces to his readers that they’re also going to die and that the book is ultimately a metaphor for human existence itself.

Conclusion

Finally, what’s a “Nivola”? Well, it’s a novel in which the characters aren’t previously defined, but are made as they move. The creator doesn’t have an outlined plan for what’ll happen, just as it happens in life itself.

The objective of the “Nivola” is none other than to confuse critics with a tendency to compare everything with other previous work. This way, it provides a new genre without precedent so there’s nothing to compare it with.

For Unamuno, there’s something fake in a realistic novel. This is because it makes the reader believe that it’s real and that’s the genre of people who don’t realize that their reality is a dream. However, the “Nivola” by Unamuno is a way of understanding any novel. One that only exists when you think, activate, and read. It’s an uncomfortable novel, in which the prologue is also a novel; in which reality and metafiction intermingle in the text.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.