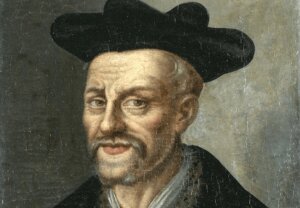

François Rabelais, the Fascinating French Satirist

François Rabelais is defined by many as a master of the unusual. In reality, both his life and work characterize him as a keen satirist. He questioned the truths of his time and exalted the human world, instead of the divine.

This fabulous French writer and doctor entered the literary world with his four novels about Gargantua and Pantagruel. A fifth was published after he died. However, many question the authenticity of its authorship. Some consider that Rabelais meant to France what Shakespeare meant to England and Cervantes to Spain.

“It’s my feeling that Time ripens all things; with Time all things are revealed; Time is the father of truth.”

-François Rabelais-

The most striking thing about his personality and his work is that critics never agreed on how to assess either. In fact, they claimed that he was an atheist, a believer, a Catholic, a Protestant, an intellectual, and a trickster. Regarding his work, they couldn’t decide if it was a bit of fun or a serious debate, comedic or philosophical, critical or trivial. These multiple interpretations prove what a genius he was.

Was François Rabelais religious?

We don’t know much at all about his early life. It isn’t even certain when exactly he was born. However, it was probably in 1494, in La Devinière, near Chinon, in Western France. There’s a cottage here where some say he was born. Nevertheless, it isn’t certain.

His father was Antonio Rabelais, a wealthy landowner. It’s thought he jointly owned several vineyards in the region with a lawyer. François went to the convent at a very young age, apparently with no vocation. However, at that time, the only way to receive an education was by joining a religious order.

François didn’t stay in one place. He started off in the Franciscan order and then moved to the Benedictines. However, this time in the convents allowed him to meet some of the brightest intellectuals of the time. In addition, he was able to study theology, Latin, Greek, astronomy, and philosophy.

A brilliant doctor

Rabelais was an anarchist. He was reluctant to follow discipline and above, all was extremely intellectually critical. Neither was he keen on living the cloistered life required of a religious order. For this reason, he left the order as soon as he could. After first serving as a secular priest, he left religious life completely.

Around 1527, he began to study medicine. In 1530, he obtained his medical degree at the University of Paris. Apparently, before even graduating, he was caring for patients, even though he wasn’t meant to.

The Renaissance was advancing, and its spirit rubbed off onto Rabelais. Thanks to his studies in classical languages, he knew the works of Galen and Hippocrates. Indeed, he admired them greatly. However, he came to question them later.

In 1532, he became a doctor in a hospital in Lyon. At the time, this city was the cultural center of France. In particular, it was the epicenter of editorial production. This was where Rabelais published his first work, Pantagruel, King of the Dispodes under the pseudonym Alcofribas Nasier, an anagram of François Rabelais.

A work for posterity

His book was immediately successful and sold everywhere. In fact, it even sold more copies than The Bible at the time. For this reason, he published a second volume just two years later, which included the characters Gargantua and Pantagruel.

Rabelais didn’t invent these characters. They already appeared in many popular legends and were also a part of Celtic mythology. It’s quite possible that they were considered as divine beings in France before Christianity prevailed. That’s why bringing them back had something of the heretical about it.

Rabelais wanted to stage human vices and virtues in a humorous way, and at the expense of the follies and exaggerations of the era. Much in the same way that Cervantes did with Don Quixote. Between the lines, Rabelais questioned many theological truths and satirized prevailing customs.

However, Rabelais’ works brought him great problems. Several times, his books were banned, both by the French parliament and the Spanish Inquisition. Before his death, he was denounced by both Catholics and Protestants and considered something of a heretic. In fact, he was possibly saved from further action by his death, believed to be on April 9, 1553, in Paris.

François Rabelais is defined by many as a master of the unusual. In reality, both his life and work characterize him as a keen satirist. He questioned the truths of his time and exalted the human world, instead of the divine.

This fabulous French writer and doctor entered the literary world with his four novels about Gargantua and Pantagruel. A fifth was published after he died. However, many question the authenticity of its authorship. Some consider that Rabelais meant to France what Shakespeare meant to England and Cervantes to Spain.

“It’s my feeling that Time ripens all things; with Time all things are revealed; Time is the father of truth.”

-François Rabelais-

The most striking thing about his personality and his work is that critics never agreed on how to assess either. In fact, they claimed that he was an atheist, a believer, a Catholic, a Protestant, an intellectual, and a trickster. Regarding his work, they couldn’t decide if it was a bit of fun or a serious debate, comedic or philosophical, critical or trivial. These multiple interpretations prove what a genius he was.

Was François Rabelais religious?

We don’t know much at all about his early life. It isn’t even certain when exactly he was born. However, it was probably in 1494, in La Devinière, near Chinon, in Western France. There’s a cottage here where some say he was born. Nevertheless, it isn’t certain.

His father was Antonio Rabelais, a wealthy landowner. It’s thought he jointly owned several vineyards in the region with a lawyer. François went to the convent at a very young age, apparently with no vocation. However, at that time, the only way to receive an education was by joining a religious order.

François didn’t stay in one place. He started off in the Franciscan order and then moved to the Benedictines. However, this time in the convents allowed him to meet some of the brightest intellectuals of the time. In addition, he was able to study theology, Latin, Greek, astronomy, and philosophy.

A brilliant doctor

Rabelais was an anarchist. He was reluctant to follow discipline and above, all was extremely intellectually critical. Neither was he keen on living the cloistered life required of a religious order. For this reason, he left the order as soon as he could. After first serving as a secular priest, he left religious life completely.

Around 1527, he began to study medicine. In 1530, he obtained his medical degree at the University of Paris. Apparently, before even graduating, he was caring for patients, even though he wasn’t meant to.

The Renaissance was advancing, and its spirit rubbed off onto Rabelais. Thanks to his studies in classical languages, he knew the works of Galen and Hippocrates. Indeed, he admired them greatly. However, he came to question them later.

In 1532, he became a doctor in a hospital in Lyon. At the time, this city was the cultural center of France. In particular, it was the epicenter of editorial production. This was where Rabelais published his first work, Pantagruel, King of the Dispodes under the pseudonym Alcofribas Nasier, an anagram of François Rabelais.

A work for posterity

His book was immediately successful and sold everywhere. In fact, it even sold more copies than The Bible at the time. For this reason, he published a second volume just two years later, which included the characters Gargantua and Pantagruel.

Rabelais didn’t invent these characters. They already appeared in many popular legends and were also a part of Celtic mythology. It’s quite possible that they were considered as divine beings in France before Christianity prevailed. That’s why bringing them back had something of the heretical about it.

Rabelais wanted to stage human vices and virtues in a humorous way, and at the expense of the follies and exaggerations of the era. Much in the same way that Cervantes did with Don Quixote. Between the lines, Rabelais questioned many theological truths and satirized prevailing customs.

However, Rabelais’ works brought him great problems. Several times, his books were banned, both by the French parliament and the Spanish Inquisition. Before his death, he was denounced by both Catholics and Protestants and considered something of a heretic. In fact, he was possibly saved from further action by his death, believed to be on April 9, 1553, in Paris.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Febvre, L. (1993). El problema de la incredulidad en el siglo XVI: la religión de Rabelais (Vol. 161). Ediciones Akal.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.